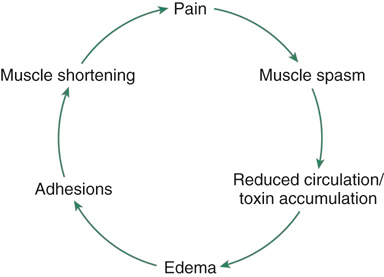

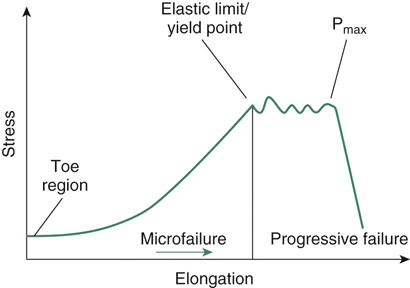

The main constituent of connective tissue is collagen. Its function is to resist axial tension, and it exhibits a stress-strain behavior (Box 27-1). Microscopically, collagen fibers are arranged in bundles and have a crimped appearance. Type I collagen is in the dermis and fascia and gives support and resistance to tension. The orientation of the fibers depends on the stresses to which the fibers are subjected; connective tissue must be pliable, yet very strong. A stress-strain curve demonstrates the behavior of biologic materials. When a longitudinal stress is applied to collagen, the tissue responds by elongation, which occurs in the toe region of the curve (Figure 27-1). Elongation occurs as a result of straightening of the crimped fibers, and probably also as a result of some interfibrillar sliding and shear of ground substance, which flows between the collagen fibers. Increased lymphatic flow is caused by the following: • Increased capillary pressure • Increased plasma osmotic pressure • Increased interstitial fluid pressure Massage has been shown to increase lymph flow rate by 22-fold, lymph colloid concentration by 47 times, and leukocyte counts by 8.5 times.1 It is believed that when tissues and fluid are compressed against the outer surfaces of the larger lymph vessels, lymph flow is impeded. This results in an increase in interstitial fluid pressure slightly above atmospheric pressure. Massaging may increase interstitial fluid pressure and help to move fluid into the lymphatic system. By massaging in a distal to proximal direction, it is proposed that fluid is moved from the extremity toward the central body core. This supports the practice of applying massage in a distal to proximal direction. Other controlled studies show that massage does not improve lymph drainage in certain situations, such as cancer. A study of women with breast cancer–related lymphedema evaluated the effect of compression garments with or without manual lymph drainage (massage). It was concluded that compression garments improved lymphedema, but there was no additional benefit of massage in relieving limb edema in women with breast cancer.2 During an actual massage session, various massage manipulations are employed that are complex and involve a combination of squeezing, stretching, pulling, and traction forces, with movement occurring in different directions and in different tissue planes. Therefore there will be complex repetitive pressure changes occurring in varying directions and at different tissue depths. This is likely to have an effect on fluid interchange, whereby fluid is pushed from the tissue spaces into the vessels, toward the lymph nodes and heart, and new fluid is pushed or drawn into the spaces. Massage is believed to replenish the fluid in the spaces, producing a flushing effect, which brings in additional nutrients. There is evidence in humans that chemical irritants in the tissues (e.g., substance P, prostaglandins) and waste products of metabolism may decrease pain threshold by sensitizing free nerve endings. Replenishing tissue fluid and removing inflammatory products may reduce this effect, preventing or reducing some types of chronic pain. By removing metabolites and chemicals from muscles and “flushing” the muscle tissue with new circulation, muscle soreness following exercise may be reduced. However, controlled studies have not been able to demonstrate that massage reduces metabolites following exercise.3,4 Studies involving Doppler ultrasound have failed to demonstrate an effect of massage on muscle blood flow.5,6 Massage involves the interaction of energy between the person applying the massage and the dog, and the effects of touch to induce relaxation, communication, and a sense of general well-being. It may also produce movement of the tissues in subsequent layers as a result of traction of the tissue interfaces. Sensory and autonomic nerves may be stimulated, inducing changes in the nervous and circulatory systems, and movement may be affected in abnormal tissue, such as scar tissue or layers of adherent tissues. Reed and Held7 found no consistent systemic effect on autonomic nervous system parameters either acutely or cumulatively when comparing connective tissue massage and a placebo treatment (sham ultrasound) in healthy middle-aged and geriatric humans. Stroking young animals results in a reduction in the animal’s physiologic response to stress, demonstrated by a decreased output of adrenocorticotropic hormone.8 Young animals that are handled also show greater development of the cortex and the subcortex of the brain. They learn faster and have a more advanced stage of neural development than nonhandled animals.9 Resistance to infection later in life may also be beneficially influenced by cutaneous stimulation experienced by the infant animal.10 Most of the research on the effects of massage has been done in humans. Most studies have evaluated healthy individuals, which may be misleading because physiologic compensatory mechanisms are extremely efficient in healthy tissues and any alterations in local blood flow may be compensated for by autoregulatory processes. Most of the research studies have also been performed on small groups and often without control groups. One study by Hansen and Kirstensen11 gave little detail concerning the massage itself, such as the amount of pressure applied. Although the research supported the concept that massage increases blood flow in muscles, the lack of information regarding the type of massage and length of treatment make interpretation of the results difficult. Changes in blood constituents following massage have provided information regarding the mechanism of action of massage.12 Ernst13 found that a standard 20-minute massage treatment reduced the hematocrit and blood and plasma viscosity. It is believed that the fluid immediately surrounding poorly perfused vessels has low viscosity because of decreased cellularity and that the vasodilatation caused by massage aids in the recruitment of dormant vessels. It is desirable to increase local circulation to promote healing. The mechanical effect of the massage helps to remove low-viscosity tissue fluid into the circulation. The changes in blood detected within the vessels in this study support the belief that massage produces a flushing and mechanical effect on the circulation. In a more recent study, Hinds and colleagues6 showed no difference in femoral arterial blood flow, quadriceps muscle temperature, blood lactate levels, heart rate, or blood pressure when comparing post quadriceps exercise and massage to exercise and rest. They did show that skin blood flow and skin temperature were both significantly elevated in the massage group. They hypothesized that this potential diversion of blood flow away from the muscle could have a deleterious effect to recovering muscle tissue. They did not demonstrate a decrease in muscle blood flow, however, so this hypothesis is not supported by their work. In a Cochrane database review, Furlan and colleagues14 critiqued 13 randomized trials and concluded that massage might be beneficial in the treatment of low back pain in acute and chronic cases, especially when combined with exercise and education. It is believed that the circulatory effect of massage may reduce muscle soreness and therefore aid clinical signs associated with muscle injury or postexercise recovery. Danneskiold-Samsoe and colleagues15 studied the effects of massage for shoulder and back pain in humans. Blood samples were evaluated for myoglobin concentrations. There was a statistically significant effect, with peak myoglobin concentrations occurring within 3 hours of the massage. Myoglobin concentrations gradually decreased; after seven treatments, there was no difference. In a systematic review of the literature published in 1998, Ernst16 concluded that most studies evaluating the effect of massage on delayed-onset muscle soreness were methodologically flawed, findings were inconsistent between studies, and, although there appeared to be some potential for a positive effect, the evidence was not convincing and warranted further controlled investigation. Jacobs17 advocated the use of massage for the relief of spasm of unknown cause but which resulted in a self-perpetuating muscle spasm cycle (Figure 27-2). Massage is also said to reduce tone in muscles that are tense or in spasm and to reduce the soreness and tenderness of exercised muscles. It is also used to prepare muscles for exercise. Hernandez-Reif and colleagues18 found that children with cerebral palsy who received 30 minutes of massage twice weekly for 12 weeks had decreased muscle spasticity of the arms, decreased arm muscle and overall tone, increased hip extension range of motion (ROM), and improved fine and gross motor function when compared with children with cerebral palsy who received 30 minutes of reading twice weekly. Jones and Round19 discussed the process by which an analgesic substance, possibly potassium, is released when muscles maintain excessive tone or static contraction for prolonged periods. Eccentric exercise of muscles, which generates high forces in muscles, produces delayed-onset soreness and a feeling of stiffness. Jones and Round19 explained this by identifying swelling in muscles and inflammation of the connective tissue. Massage may help reduce or prevent the initial tenderness. It is also believed that massage may help to prevent subsequent postexercise pain. Regular massages may make the muscles softer and more pliable, and the stretching manipulations may increase extensibility and strength in the connective tissues.15 Willems and colleagues20 demonstrated decreased muscle soreness in portions of the quadriceps muscle (vastus lateralis and rectus femoris), but not in the vastus medialis after massage following eccentric exercise–induced muscle soreness. They also demonstrated improved vertical jumping performance in the massaged leg 48 hours after massage when compared with the nonmassaged leg. Mancinelli and colleagues21 showed significant effects of massage versus control in vertical jump displacement, perceived muscle soreness, and algometer muscle pain readings, but not timed shuttle run in women collegiate athletes. The effects of massage on the Hoffman (H) reflex, which indicates the excitability in α-motoneurons or anterior horn cells, has also generated interest. Goldberg and colleagues22 studied the effects of massage on healthy people and patients with spinal cord injuries. They applied one-handed petrissage to deep and superficial tissues. There was a 49% reduction in H reflex activity with deep massage, and a 39% reduction with light massage. From this study, it was concluded that stimulating cutaneous mechanoreceptors and pressure receptors reduces H reflex activity. Sullivan and colleagues23 also demonstrated a reduction in α-motoneuron excitability of massaged muscles. The effects of massage on connective tissues, which helps to reduce muscle spasm and soft tissue discomfort, have already been discussed. However, Ueda and colleagues24 demonstrated that postsurgical massage may facilitate the regression of sensory analgesia following an epidural block. Carreck25 evaluated the effect of massage on levels of pain perception in humans. She found that pain threshold was raised to significantly higher levels in the massage group and this work suggests that massage may be used to help manage pain and reduce treatment soreness. One technique to mobilize scar tissue is deep-friction massage.26 It is applied at 90 degrees to the fibers and delivers a stretch and separation between individual fibers. Deep friction is believed to create movement and induce reactive hyperemia,27 stretch cross-bridges between fibers, and stretch adhesions within the structure. Fibrous scarring in tendons and their interfaces may become more pliable with massage. Although one researcher has suggested that deep friction application may result in some analgesia to the area,28 there is little evidence to support this claim. Although many theoretical effects of massage have been put forth, there is little high-quality research evidence to support these claims. A Cochrane review evaluating the effect of deep transverse friction massage for treating tendinitis found no evidence of benefit with its use and concluded that there was the need for a high-quality randomized study using validated outcome measures to further evaluate its usefulness.29

Massage

Biologic Basis

Biomechanics of Connective Tissue

Figure 27-1 Typical stress-strain curve for connective tissue. Stress, Force applied per unit area; strain, proportional elongation; Pmax, maximum load point.

Lymphatics

Circulatory Effects

Tissue Movement

Therapeutic Effects

Effects on Muscle

Effects on Pain and Sensation

Effects of Massage on Connective Tissue

Indications for Massage

Mechanical

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree