CHAPTER 101 Management of Rectal Tears

The rectum extends from the pelvic inlet to the anus and is a storage chamber for feces. It is approximately 30 cm long and is divided into a peritoneal and a nonperitoneal section. The peritoneal rectum is a continuation of the small colon, and this determines its position, which is most commonly in the left dorsal aspect of the pelvic cavity.

DIAGNOSIS

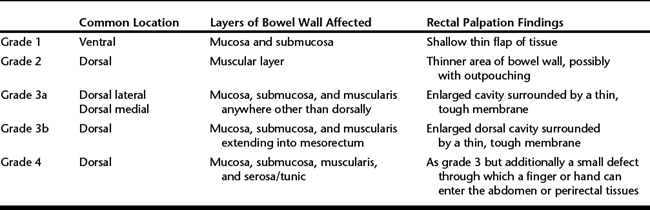

Tears are graded according to the involvement of the layers of the bowel wall as initially reported by Arnold and colleagues in 1978 (Table 101-1). Tears can be located at any distance from the anus; however, most are 25 to 30 cm from the anus at the junction of the rectum and small colon. This area is considered to be predisposed to injury because the blood vessels penetrate the intestinal wall acutely and directly rather than gradually, therefore causing weakening in the dorsal aspect of the wall. Iatrogenic tears are most commonly longitudinal, but idiopathic tears may be transverse.

TREATMENT

Grade 3 and 4 Tears

Rectal packing may predispose to worsening of the tear through manual trauma and an increase in intrarectal pressure, especially if the horse strains. If a rectal tampon is not used, it may be sufficient to ensure the rectum is fully evacuated and that the horse is treated with parasympatholytics such as butylscopolamine bromide (0.3 mg/kg IV) and epidural anesthesia, which in combination should decrease straining and facilitate fecal passage.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree