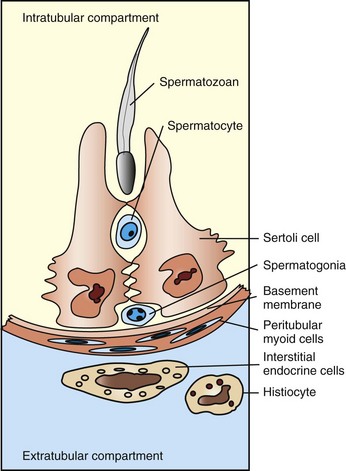

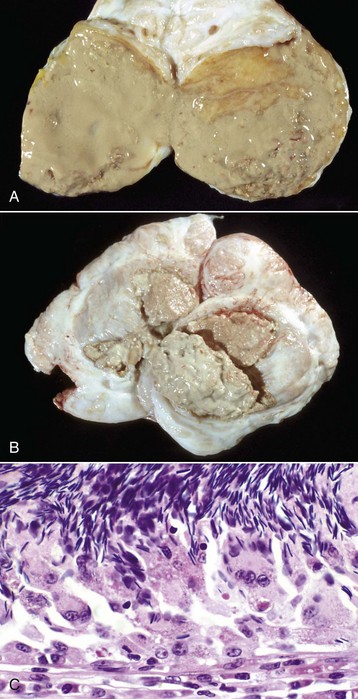

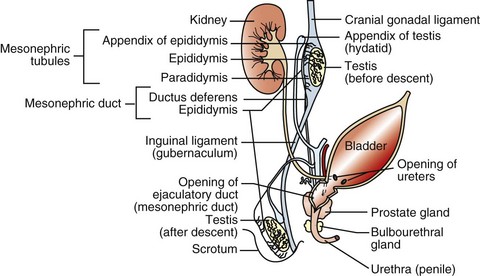

CHAPTER 19 Sertoli cells provide support, nutrients, hormones, and cytokines to permit spermatogenesis. During spermatogenesis, the cells pass into a region that is separated from and external to the immune system of the body. The barrier is called the blood-testis barrier, and it is maintained by the Sertoli cells (Fig. 19-1). Control of spermatogenesis is achieved through a combination of both central (luteinizing hormone [LH] on the interstitial endocrine cells and follicle-stimulating hormone [FSH] on Sertoli cells) and local (paracrine and autocrine molecules, including testosterone) factors, and there is considerable crosstalk between germ cells, Sertoli cells, and interstitial endocrine cells. Local modification of spermatogenesis is achieved through increased or decreased apoptosis at any stage of development. Many of the disorders and conditions that affect spermatogenesis increase or decrease the apoptotic rate. Fig. 19-1 Schematic diagram of the normal components of the testis. The formation of spermatic granulomas (Fig. 19-2) is one of the most dramatic and important responses of the male reproductive system to injury. Spermatic granulomas occur with rupture of a duct; spermiostasis and spermatocele are the usual preliminary stages. Spermatozoa are “foreign” to the body. Immunity to spermatozoa with the formation of antisperm antibody is a well-recognized phenomenon. The cell wall constituents and the high chromatin content make them resistant to degradation. Any injury that exposes spermatozoa to the tissue of the body results in severe inflammation, mostly of a granulomatous type. This can be a foreign body type response, an immunologic response, or both. The inflammation produced is usually chronic and results in severe scarring, which further obstructs tubules and ducts, leading to even more inflammation so that it becomes self-perpetuating. It is therefore critical to prevent such injury. Fig. 19-2 Spermatic granulomas, tail of the epididymis, ram. There are four main portals of entry of infectious and injurious agents to the male reproductive tract (Box 19-1). They include direct penetration and injury, ascending infection, hematogenous localization, and peritoneal spread. In general terms, inflammation of the male reproductive tract is similar to that of other systems. What is unique about the male genital tract is inflammation to spermatozoa. Spermatozoa and germ cells outside the blood-testis barrier are antigenic. There are also antigenic components within seminal fluid. Spermatozoa have antigens that attract immune cells and also nonspecifically bind immunoglobulin. These reactions can have a minimal effect on the tissues directly and act by agglutinating spermatozoa or by opsonization. In some instances, the effect is much more dramatic and immunization against spermatozoa can result in a severe inflammatory response. This inflammation can be local or spermatozoa can be “attacked” in those areas in which the tissue-spermatozoal barrier is the weakest. In many species, this is the region of the efferent ductules and the epididymis. This so-called autoimmune reaction to spermatozoa can be experimentally created, but a clinical correlate is infrequent. Local effects, however, are much more recognized. Direct damage to testicular parenchyma can result in granulomatous inflammation centered on the seminiferous tubules, the so-called intratubular orchitis. Where spermatozoa are exposed to the tissues of the body, the reaction is that of granulomatous inflammation. Macrophages and multinucleate giant cells are found adjacent to spermatozoa (see Fig. 19-2, C). Initially at least, CD4+ T lymphocytes are abundant. Immunoglobulin-producing cells, particularly IgG-containing cells, are found. Granulomas are formed with the characteristic appearance of layers of epithelioid macrophages with multinucleate giant cells and then lymphocytes and plasma cells with a surrounding of fibrous tissue. In advanced cases, inspissated spermatozoa are found within a fibrous capsule. The production of a fibrous capsule and resultant contraction leads to further obstruction to the various adjacent ducts and tubules, with the result that additional spermiostasis, spermatocele, and spermatic granuloma formation continues. This inflammation therefore has devastating effects on fertility. Further complications occur if spermatozoa are released into the cavity of the vaginal tunics because a severe periorchitis develops and results in fibrosis and the lack of ability to adequately thermoregulate the testes. There are many different ways to approach disorders of the male reproductive system (see Appendix 19-1). Each approach has its own advantages and disadvantages. Some of the disorders affect more than one region, yet there are many disorders that have a primary manifestation in one anatomic location. Approaching disorders from a pathogenetic viewpoint is logical; however, it does not always account for clinical relevance or assist in the correlation between clinical signs and prognosis. Disorders are approached based on their anatomic location: scrotal contents, accessory genital glands, and the penis and prepuce—this approach is more clinically relevant. Before doing so, it is prudent to examine disorders of sexual development (DSD) because they fall in a distinct category. There are a large number of anomalies of the male reproductive system (Box 19-2). Some have clinical relevance and others do not. Differentiating between these is very important. Some of the anomalies represent the most common disease of a particular species. Where this is the case, the disease is discussed under disorders of a particular anatomic location because this is the most clinically relevant place. We have attempted to divide the various anomalies into those that are major and minor based on effects on fertility and on the future breeding potential of the animal. Some anomalies have a genetic basis and such individuals should not be used as a stud animal, even though the animal may still be fertile. Normal males have an XY chromosomal sex. The differentiation of the bipotential fetal gonad to a testis depends on the presence of a gene—the sex-determining region of the Y chromosome (SRY) that codes for the testis-determining factor and on other genes that cause the germ cells to go into mitotic arrest. Supporting cells become the Sertoli cells, the steroid-producing cells become the interstitial endocrine cells (Leydig cells), and the mesenchyme develops the appearance of a testis. Further development requires the activation of many other genes that are not on the Y chromosome. The expression of SRY occurs briefly in the somatic cells of the indifferent gonads (or genital ridges). Because expression ceases shortly before Sertoli cells can be recognized, it is proposed that the functional gene product of SRY influences other genes, such as SOX9, that ensure the differentiation and maintenance of Sertoli cells. SOX9 is upregulated in XY individuals just before gonadal differentiation. Sertoli cells signal the other supporting cell precursor lines to differentiate along the male pathway. Early in sex differentiation, the embryo has a double set of ducts. The paramesonephric (Müllerian) ducts are female precursors, arising by invagination of the celomic cavity. The mesonephric (Wolffian) tubules and ducts are male precursors, arising from the primitive kidney, the mesonephros. The rete testis and efferent ductules are derived from mesonephric tubules. There are about 20 efferent ductules, although the number varies with species. The epididymis is derived from the part of the mesonephric duct within the mesonephros. The deferent duct, ampulla, and vesicular gland are derived from the distal part of the mesonephric duct, outside the mesonephros (Fig. 19-3). Fig. 19-3 Schematic diagram of the normal components of the male reproductive system and the embryonic structures, especially the mesonephric (Wolffian) duct and urogenital sinus and tubercle, from which they were derived. The most common and important major anomaly of the male reproductive system is failure of testicular descent or cryptorchidism. Testicular hypoplasia and segmental aplasia of the epididymis are a close second. These disorders and conditions are discussed further in the section on Disorders of the Scrotum and Contents. Much less common, but nevertheless important, are other DSD. Disorders of Sexual Development: Errors of chromosomal, gonadal, or phenotypic sex are usually manifested by abnormalities in sexual dimorphism. Many of the abnormalities result in a female phenotype and are mentioned in more detail in Chapter 18. The concentration here is on those disorders that involve animals that have male gonads or are predominantly phenotypic males. One cannot always tell the underlying cause of sexual ambiguity by examining phenotype or even identifying the gonadal type. Complete definition of a DSD requires knowledge of all three components: chromosomal, gonadal, and phenotypic types. Chromosomal Disorders of Sexual Development: Sex chromosomes can be abnormal in structure or number. Two examples of abnormal structure of the Y chromosome are deletion of the short arm and isochromosome formation (duplication of one arm and loss of the other). Affected individuals have a female phenotype and extremely hypoplastic gonads. A few cattle have been identified with an isochromosome Y. With duplication of one of the sex chromosomes in an individual with a Y chromosome (XYY or XXY), or a mosaic (as occurs with the calico or tricolor male cats), the external genitalia are male in character. Klinefelter syndrome (XXY) is discussed in the section on Testicular Hypoplasia. Chimeras, such as XX/XY, are phenotypically sexually ambiguous, and the degree depends on the relative amounts of each chromosome. Freemartins are chimeras and are discussed in Chapter 18. XX Disorders of Sexual Development: Animals with an XX genotype, testicular tissue, and a male phenotype are called XX sex reversal individuals. They may be SRY positive or SRY negative. XX SRY-negative DSD is reported in many breeds of dogs, in goats, and in horses. Affected individuals have an ovotestis or testis. Those with ovotestes or a testis and an ovary are called hermaphrodites. Some ovotestes have an end-to-end arrangement of ovarian and testicular tissue, with clear demarcation between the two. Others have central testicular tissue with a periphery of ovarian structures. Bilateral hermaphrodites have an ovotestis on each side; unilateral hermaphrodites have an ovotestis on one side; and lateral hermaphrodites have a testis on one side and an ovary on the other. The genital tract in hermaphrodites is ambiguous and can be phenotypic male, female, or various combinations of the two, depending on the amount of hormones, including testosterone and AMH. It is assumed that XX SRY-negative individuals have a testis-determining region on another chromosome. XX SRY-positive DSD is not reported in domestic mammals. XY Disorders of Sexual Development: There are three classifications of XY disorders of sexual development; those with disorders of gonadal development (gonadal dysgenesis, ovotestes, or aplasia), disorders of androgen synthesis or action, and miscellaneous types. They can be either XY SRY-positive or XY SRY-negative. XY DSD are identified in many species, including dogs and horses. XY SRY-negative individuals usually have primitive and undifferentiated gonads, called gonadal dysgenesis, and a female phenotype. Their classification is therefore XY SRY-negative, gonadal dysgenesis DSD. XY SRY-positive individuals with a female phenotype usually have testes and are called male pseudohermaphrodites (Figs. 19-4 and 19-5). The differentiation of the genital tract can be slightly or greatly abnormal. In many cases, the mechanism for the abnormal differentiation is unknown, but there are well-recognized syndromes in which the underlying pathogenesis is known. Three such syndromes are persistent Müllerian duct syndrome (PMDS), androgen insensitivity, and steroid 5α-reductase deficiency. Fig. 19-4 XY disorder of sexual development, male pseudohermaphrodite, external genitalia, boar. Fig. 19-5 XY disorder of sexual development, male pseudohermaphrodite (male feminization syndrome), reproductive tract, ram. Androgen receptor disorders are becoming increasingly recognized. Most cases are caused by a mutation in the androgen receptor gene, which is located on the X chromosome and thus in a single copy. Hundreds of mutations have been identified in other species, and the effects range from complete androgen insensitivity with female external genitalia (testicular feminization) (see Fig. 19-5) to mild male pseudohermaphroditism. The testes produce testosterone, but the stimulation of the mesonephric system is not normal because of defective androgen receptors. The normal androgen receptor has a hormone-binding and a DNA-binding domain; once activated by androgen, the domain changes shape and is able to bind to specific DNA sequences and regulate the transcription of other specific genes, leading to normal male differentiation. In humans with androgen insensitivity, the gene is rarely deleted, but numerous point mutations in the receptor gene have been identified, mostly in the hormone-binding and DNA-binding domains. Whether the result is partial or complete androgen insensitivity depends on the location of the mutation and the change in function of the receptor. Dihydrotestosterone binds to the androgen receptor with greater affinity than that of testosterone, and the receptor, when it acts as a transcriptional factor, might interact with different genes other than the testosterone-bound receptor. In domestic animals, complete androgen insensitivity is described in the equine, bovine, and feline species. The testes are often cryptorchid and are in the inguinal area. The first and second phases of testicular migration is normal. The inguinoscrotal third phase, which is under the control of androgens, does not occur. AMH produced by the testes causes regression of the paramesonephric ducts. External genitalia are female in complete androgen insensitivity, with a cranial blind end to the vagina, and neither the paramesonephric nor mesonephric ductal system is present. Cryptorchidism is an XY SRY-positive DSD but is examined in detail as a separate entity in the discussion of the testis in the section on Disorders of the Scrotum and Contents. Segmental Aplasia of Mesonephric Duct Derivatives: Segmental aplasia of the structures of mesonephric ductal origin (epididymis, deferent duct, ampulla, or vesicular gland) can involve any of the structures, but it most commonly involves the epididymis alone (Fig. 19-6) and less commonly other structures. Segmental aplasia is reported mainly in the bull and most commonly involves the body and tail of the epididymis and is unilateral. Its inheritance is thought to be autosomal recessive. Spermatozoa become impacted because the epididymal duct is blind ending; local dilation or rupture occurs secondarily, allowing escape of spermatozoa and formation of spermatic granulomas. Ciliary Dyskinesia (Immotile Cilia Syndrome): One or more of several defects in the axoneme of cilia throughout the body and of the flagellum of spermatozoa causes ciliary dyskinesia, a rare disease identified in humans, dogs, pigs, mice, and rats. An autosomal recessive mode of inheritance is proposed. In dogs, heterogeneity of ultrastructural abnormalities of microtubule doublets and their dynein arms or central microtubules is reported. The effect on the reproductive system is immotile or hypomotile spermatozoa caused by flagellar lesions or to oligospermia (a subnormal concentration of spermatozoa) or azoospermia (no spermatozoa), presumably because of defective cilia in the epididymis and deferent duct. Because of defective cilia in the nasal mucosa, bronchial and bronchiolar mucosa, and ependyma, commonly associated lesions are rhinitis, bronchopneumonia, bronchiectasis, and hydrocephalus. Also associated is situs inversus, but the pathogenesis of the reversal of the normal left and right orientation of organs is unclear. Female infertility is related to defective function of cilia of the uterine tube. Cysts of the Male Tract: It is often difficult to identify the origin of an individual cyst or group of cysts. In many instances, anatomic location is the determining factor. Many of the cysts are simply called inclusion cysts (Fig. 19-7). These have a wall of compressed collagen, a thin inner lining of flattened cells, and a clear fluid content. They are found where mesothelial cells are trapped adjacent to a serosal surface. Inclusion cysts attached to the head of the epididymis are good examples.

Male Reproductive System

Structure

The Scrotum and Contents

Cell Types

The Sertoli cells, germ cells, and interstitial endocrine cells are closely integrated, and considerable messaging occurs between them. The blood-testis barrier is at the level of the Sertoli cells, with contributions from the myoid cells and basement membrane. Spermatogonia are on the interstitial side of the blood-testis barrier.

Responses to Injury

A, Most of the tail of the epididymis (bisected and reflected) has been replaced by a yellow-tan, semiliquid spermatic granuloma. These granulomas are any color from white to red. They are frequently and incorrectly called abscesses. B, Multiple encapsulated (chronic) spermatic granulomas with white caseous centers. C, A mass of spermatozoa free in the interstitium (upper half of image) is surrounded by epithelioid macrophages and multinucleated giant cells, some of which have phagocytosed spermatozoa. Lymphocytes, plasma cells, and fibrous connective tissue surround these granulomas (lower half of image). H&E stain. (A and B courtesy Drs. P. W. Ladds and R. A. Foster, James Cook University of North Queensland. C courtesy Dr. R. A. Foster, Ontario Veterinary College, University of Guelph.)

Portals of Entry

Defense Mechanisms

Inflammation

Disorders of Domestic Animals (Horses, Ruminants [Cattle, Sheep, and Goats], Pigs, Dogs, and Cats)

Disorders of Sexual Development

Male Embryology

The rete tubules and efferent ductules are formed from the mesonephric ductules; the epididymis, deferent duct, ampullae, and vesicular glands form from the mesonephric duct; the prostate and bulbourethral glands form from the urogenital sinus; and the penis, prepuce, and scrotum form from the genital tubercle and swellings.

Major Anomalies

This pig has a scrotum and intrascrotal testes, but the penis is small and clitoris-like and has a terminal urethral opening (ventral to the tail). (Courtesy Dr. D. Dodd; and Noah’s Arkive, College of Veterinary Medicine, The University of Georgia.)

This sheep has testes, deferent ducts, and accessory genital glands but also a vulva and a prominent clitoris. An androgen receptor defect would explain these anomalies. (Courtesy RA Foster, Ontario Veterinary College, University of Guelph.)

Minor Anomalies

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree