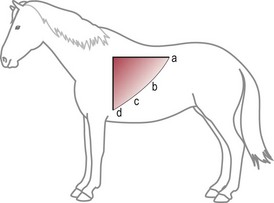

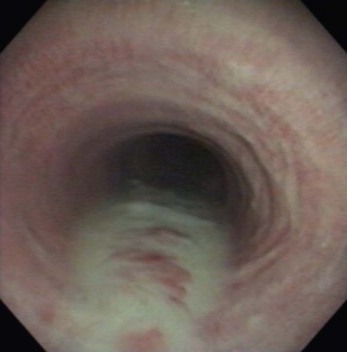

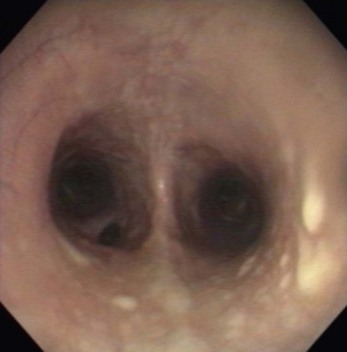

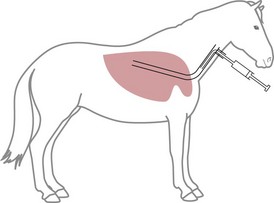

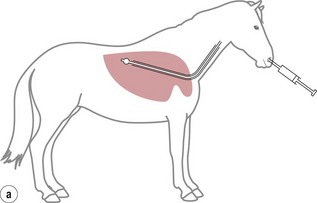

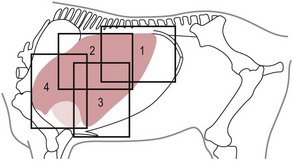

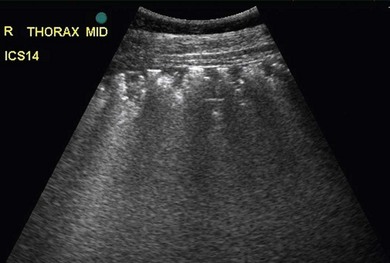

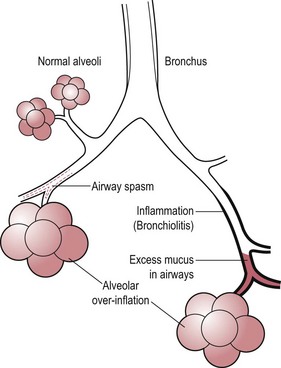

Chapter 6 6.1 Diagnostic approach to lower respiratory tract diseases 6.2 Diagnostic features of the common lower respiratory tract diseases of the adult horse 6.3 Recurrent airway obstruction (RAO) 6.4 Acute obstructive pulmonary disease 6.5 Summer pasture-associated obstructive pulmonary disease (SPAOPD) 6.6 Inflammatory airway disease (IAD) 6.7 Exercise-induced pulmonary haemorrhage (EIPH) 6.8 Lungworm (Dictyocaulus arnfieldi) infection 6.9 Parascaris equorum infection 6.11 Pulmonary/pleural/mediastinal neoplasia 6.13 Rhodococcus equi pneumonia 6.14 Interstitial pneumonia/chronic interstitial inflammation 6.15 Acute interstitial pneumonia in foals History: History and signalment can be important in aiding diagnosis of horses with respiratory diseases. Important points include: • Age – many contagious diseases, including strangles and Rhodococcus equi infection, are most frequently seen in young horses, whereas allergic diseases such as recurrent airway obstruction (RAO) are usually seen in mature horses. • Health of in-contact horses – similar clinical signs among in-contact horses suggests contagious disease. • Environment – RAO is most likely in stabled horses or horses exposed to hay and/or straw. Dictyocaulus arnfieldi infection is most likely in horses grazing pasture contaminated by donkeys. • Seasonality – seasonal disease in horses at grass is suggestive of summer pasture-associated obstructive pulmonary disease (SPAOPD). • Stress – severe respiratory disease occurring in a recently stressed horse (such as after long distance travel or surgery) should arouse suspicion of pleuropneumonia. Physical examination: The physical examination should be performed in a quiet environment with the horse relaxed and rested. Examination during and after exercise may be required subsequently. Systemic and extra-thoracic signs that may occur with lower respiratory tract disease include: Respiratory rate, pattern and character: The rate, depth, and pattern of breathing should be noted, as should any abnormal sounds associated with breathing. This is best done by distant observation with the horse in a quiet location. The breathing is most easily assessed by observing the movement of the costal arch whilst standing caudolaterally to the horse. Alternatively, the respiratory rate may be measured by feeling airflow with a hand placed close to the external nares. • Normal respiration in the resting adult horse is slow (8–16 breaths/min) with minimal chest or abdominal wall movement. Ponies may have a slightly higher resting respiratory rate (up to 20 breaths/min). During quiet breathing, resting horses normally have only slight movements of the nostrils and costal arch. Increased depth of breathing (with or without an increased rate) is abnormal, and its character should be noted. • Normal horses have biphasic inspiratory and expiratory phases. The end expiratory abdominal lift is often visible in normal horses, and does not necessarily indicate disease. • Expiratory dyspnoea (Box 6.1) results in an exaggeration of the biphasic expiratory phase with increased incorporation of the abdominal muscles producing an obvious biphasic or double expiratory lift (‘heave’), which is typical of small airway obstruction. • Inspiratory dyspnoea associated with a stertorous or stridorous noise during inspiration (Box 6.1) is indicative of upper airway obstruction. Occasionally, inspiratory dyspnoea may occur with severe restrictive lung diseases (e.g. pneumonia, interstitial disease, pneumothorax, rib fracture). • Combined inspiratory and expiratory dyspnoea, usually with tachypnoea, is suggestive of severe upper or lower airway obstruction, diffuse pulmonary disease or pleural disease. • Unilateral nasal discharges usually originate from the nasal chamber and paranasal sinuses. Drainage from the guttural pouch will be reported by the owner as unilateral or predominately unilateral discharge. • Bilateral discharges can arise from the upper or lower respiratory tracts. • Serous nasal discharges are commonly seen in viral infections, although they frequently change to mucopurulent or purulent with secondary bacterial infection. • The presence or absence of odour or food material in the discharge is also helpful in determining the cause. • Coughs originating from upper airway infections are usually harsh, dry, hacking and non-productive. • Coughs originating from the lower airway are usually deep, soft and productive. The intra-narial position of the equine larynx usually precludes the coughing up of sputum directly into the mouth, but the observation of swallowing after a cough indicates that the cough is productive. • Short, painful coughs, associated with reluctance to move or to lie down, are typical of pleural disease and pain (pleurodynia). • Laryngeal palpation – see Chapter 5. • The cervical trachea is palpated for abnormalities of structure. The space between the cricoid cartilage and the first tracheal cartilage ring (the cricotracheal ligament) is normally wide. Palpation of the cervical trachea can detect pain, swellings, deformities, developmental defects (e.g. dorso-ventral or lateral collapse), and misalignment of the free borders of tracheal rings. • The bases of the jugular grooves are palpated for the presence of a mass which may indicate a mediastinal tumour that has extended rostrally through the thoracic inlet; these cases often have subcutaneous sternal / pectoral oedema as well, due to venous obstruction. • Distension of the jugular veins or the presence of an abnormal jugular pulse indicates primary cardiac disease or compression of the heart/vessels by a mass or fluid. • The chest wall should be palpated if there is a possibility of thoracic trauma (e.g. newborn foals with rib fractures). Auscultation: Auscultation is performed on both sides of the chest and over the cervical trachea. Lung sounds will vary depending on the body condition and depth of breathing. In fat horses, airflow sounds may be difficult to appreciate; these sounds can be accentuated by using a re-breathing bag (place a large plastic bag over the nose and let the horse breathe into and out of the bag until the arterial carbon dioxide tension increases, thereby increasing the depth of respiration) (Figure 6.1) or by temporarily occluding the nostrils. The normal margins of the lung fields are level with the tuber coxae at the 18th rib, mid thorax at the 13th rib, shoulder at the 11th rib, and then curving down to the level of the elbow (Figure 6.2). • Normal airflow sounds are most readily appreciated over the distal cervical trachea and at the area around the carina, and may be difficult to perceive at the lung periphery. • Normal airflow sounds are slightly louder on the right side than the left and louder during inspiration than during expiration. • Increased audibility of normal breath sounds occurs with hyperventilation and focally over areas of consolidated lung tissue. • Reduced audibility of normal lung sounds is common in obese horses. Regional loss of lung sounds occurs when the pleural cavity contains air, fluid or abnormal tissue. • A generalized increase in the intensity of airflow sounds is suggestive of lower airway disease such as RAO. • A localized absence of sounds may indicate a pulmonary or pleural abscess/tumour. • Absence of sounds in the ventral thorax (may be bilateral) suggests a pleural effusion. • Absence of sounds in the dorsal thorax is suggestive of pneumothorax. • It is not unusual to detect borborygmi referred from the abdomen during auscultation of a normal thorax. • Wheezes and crackles can sometimes be heard at the nares with the naked ear. • Crackles are produced by the sudden ‘popping’ open of airways that were closed during expiration. They are most commonly heard during inspiration, and can be detected in RAO and acute obstructive pulmonary disease, and pulmonary oedema. • Wheezes are musical notes produced by air flowing through narrowed airways. They occur in obstructive lower airway diseases including RAO and bronchopneumonia. • Coarse crackles may be heard over the distal cervical trachea (tracheal rattle). These are ‘bubbling and crackling’ sounds caused by air bubbling through excessive mucus in the airways. • The gliding movements of the visceral and parietal pleura are normally silent. Pleural friction sounds are crunching/creaking sounds that may be detected early in cases of pleuritis, due to the rubbing together of inflamed pleural surfaces. They are usually absent once a pleural effusion has formed. Percussion: Percussion may be used to detect pleural and superficial pulmonary lesions. It is less sensitive than ultrasonography. A plexor and pleximeter may be used, or, alternatively, the fingers can be employed to sharply tap over the intercostal spaces (Figure 6.3). The area of percussion is similar to the area of auscultation, remembering that there is an area of cardiac dullness (larger on the left than the right) in the ventral thorax. The entire chest on both sides should be percussed working in parallel lines from dorsal to ventral and anterior to posterior. Endoscopy: Endoscopy allows direct visualization of many parts of the respiratory tract, and the use of flexible fibreoptic or videoendoscopic equipment has become an essential component in the evaluation of respiratory tract diseases. The parts of the tract that are accessible to examination are determined by the equipment available. Although a narrow 1 or 1.2 m endoscope will permit examination of most parts of the upper respiratory tract in adult horses, it is unlikely to have sufficient length to allow examination of the bronchial tree – an instrument of 2 m or longer is needed for bronchoscopy. Fine paediatric endoscopes may be required for foals. Adequate disinfection of the instrument between horses is essential to prevent cross-infection. The trachea can be examined in its entirety if a sufficiently long endoscope is used (>1.8 m). Strictures of the tracheal lumen (congenital, iatrogenic or traumatic) can be observed, although radiography may yield more useful information. Discharges often accumulate at the thoracic inlet (Figure 6.4), and their nature (mucus, purulent material, blood) can be assessed and samples obtained by aspiration. A haemorrhagic discharge observed after exercise is suggestive of exercise-induced pulmonary haemorrhage. Foreign bodies such as brambles may lodge in the distal trachea/main bronchi and are an uncommon cause of chronic coughing – they can usually be identified and retrieved during endoscopy. The bronchial tree can be examined as far as the length and diameter of the endoscope permits. The carina (Figure 6.5) normally presents as a sharp angle at the junction of the right and left principal bronchi. Thickening of the angle (owing to mucosal oedema and inflammation) and hyperaemia may be seen in chronic lower airway diseases. A unilateral purulent discharge draining from only one principal bronchus indicates a focal lung lesion on that side (e.g. focal pneumonia, pulmonary abscess or foreign body). Passage of the endoscope down the bronchial tree may induce significant coughing which renders the examination difficult. This reaction can be reduced by repeated infusions of small volumes of dilute lidocaine solution as the endoscope is advanced. The bronchial walls can be assessed for thickening, inflammation and collapse. Lungworms (Dictyocaulus arnfieldi), foreign bodies and endobronchial tumours may be identified. Tracheal aspiration: Samples of lower airway secretions may be obtained for cytology or culture. Tracheal aspirates can be collected by endoscopy or by a transtracheal technique. In the former, the flexible endoscope is passed in the usual way via the nares into the trachea. When the tip has reached the distal trachea, a catheter is passed down the accessory port until it protrudes from the end. Sterile saline (10–15 mL) is injected through the catheter, which forms a pool at the thoracic inlet. The catheter tip is positioned into this pool and the sample is aspirated. Only a small proportion of the delivered fluid is likely to be retrieved. Aspirates from normal horses contain mainly ciliated epithelial cells and macrophages. Approximately 10% of the cells are neutrophils, although some stabled horses may have up to 40% neutrophils. • An increase in numbers of neutrophils indicates inflammatory lower airway disease, such as RAO, bronchopneumonia, etc. • Large numbers of eosinophils are seen in lungworm infections and ascarid migrations in young horses. Samples obtained by transtracheal aspiration are collected aseptically and are suitable for both cytology and culture. An area over the lower third of the cervical trachea is clipped and prepared aseptically, and an over-the-needle cannula is inserted between two tracheal rings into the tracheal lumen. A catheter is then threaded through the cannula and passed to the level of the thoracic inlet where lavage with 20–30 mL of sterile saline is performed (Figure 6.6). In cases of lower airway or pulmonary infection, a Gram-stained smear of a sample obtained in this way may give an early indication of the types of bacteria involved before culture results are available. Both aerobic and anaerobic cultures should be performed in cases of pneumonia/lung abscess. Several complications may arise following the transtracheal aspiration technique: • Damage to the tracheal cartilage, with resultant chronic infection. • Breaking of the catheter within the trachea. Most horses will cough up the damaged catheter within 30 minutes. • Breaking of the catheter in a subcutaneous site as a result of initial misplacement of the cannula/needle. The catheter must be removed surgically in these cases. • Local infection/cellulitis at the site of tracheal puncture owing to contamination of the site by bacteria from the lower airways. • Laceration of a carotid artery resulting in rapid cervical swelling and dyspnoea. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL): BAL is used to obtain samples of lower airway secretions, primarily for cytology, from the small airways and alveoli. The technique may be performed through an endoscope (which is lodged in a bronchus prior to lavage) or blindly using a catheter passed per nasum into the bronchial tree. Endoscopic BAL technique: A 120 cm (or longer) endoscope is passed in the usual way to the carina and then into a mainstem bronchus. It is advanced down the bronchial tree until it wedges in an airway (usually about a fourth to sixth generation bronchus if an endoscope with an external diameter of >8–10 mm is being used). Lavage is performed via the accessory channel of the endoscope with or without a catheter. Coughing can be severe as the endoscope passes down the bronchial tree. In most horses this abates after 10–20 seconds, but in horses with airway inflammation coughing can be persistent, in which case this can be reduced by infusing a small volume of dilute lidocaine solution (0.4%) at each bronchial division. Blind BAL technique: Commercially available nasobronchial BAL tubes should be used for the purpose when the technique is performed blindly. The tubes usually have an inflatable cuff at the distal end. With the horse’s head extended, the tube is passed in the same way as the endoscope through the nasopharynx, into the trachea until a cough reflex is elicited. Infusion of dilute lidocaine solution (as for the endoscopic technique) will alleviate the coughing, and permit the tube to be advanced down the bronchial tree (the tube most commonly enters the right dorsocaudal lung). When the tube becomes lodged and will not advance any further, the cuff is gently inflated with 5–10 mL of air, lavage fluid is instilled and the sample is recovered by manual or automated aspiration (as for the endoscopic technique) (Figure 6.7a,b). Excessive negative pressure for aspiration (manual or automated) will collapse small airways, limiting the recovery volume, and may result in blood contamination of the sample. Thoracic radiography: In adult horses, only lateral views are possible. Four overlapping fields are often required to cover the entire thorax in adult horses (Figure 6.8). An air gap is used between the patient and the film to avoid the use of a grid. Lesions that can be detected include pulmonary consolidation/pneumonia, lung abscesses, advanced EIPH lesions, lung infiltrates such as neoplasia, granulomas and fibrosis, and pleural effusions. Diagnostic ultrasound: Ultrasonography is well suited to the investigation of pleural diseases, especially pleural effusions, where the technique can provide some clues as to the nature of the fluid (i.e. transudate or exudate), as well as the presence of adhesions and loculations. Consolidated lung, pulmonary abscesses and pulmonary masses may also be imaged if these lesions are adjacent to the pleural surface. Ultrasound waves are not transmitted through aerated lung, so the technique is of little value in airway disease or focal lung diseases where the diseased area lies deep to the lung surface. The ribs can also be imaged by ultrasound. Commonly identified abnormalities include: • Pleural effusion (Figure 6.9) – separation of the parietal and visceral pleura by a band of hypoechoic material (fluid) deep to the intercostal muscles and superficial to the lungs. The echogenicity of the fluid varies depending on its nature (anechoic fluid represents fluid of low cellularity/protein content, whereas echogenic fluid indicates fluid with high cellularity/protein concentration). In the standing horse, free fluid will gravitate to the ventral thorax. • Pleuritis – a roughened texture of the pleural surface causes narrow streaks of reverberation artifacts, commonly referred to as ‘comet tails’ (Figure 6.10). Comet tails can sometimes be identified in normal lungs, especially ventrally at the end of expiration. In chronic pleuritis, adhesions between the visceral and parietal pleura may restrict the normal gliding motion. • Pleural effusion with fibrin/fibrin tags – linear echogenic structures that extend from the pleural surface into a region of effusion. These bands may float or wave within the pleural fluid. • The pericardiodiaphragmatic ligament can be imaged in the ventral thorax in horses with pleural effusion (Figure 6.9). This linear soft-tissue structure is a normal structure that should not be mistaken as a fibrin tag. It is attached at either end and will float or wave during the respiratory cycle. • Atelectasis and consolidation – consolidated lung appears similar to liver (‘hepatized’) with tubular, hypoechoic branching vascular structures. • Pulmonary mass – if a mass contacts the pleura it will be visible ultrasonographically, but not if it lies deep to aerated lung. • Pnemothorax – this will cause a reverberation artefact without the normal gliding appearance of the pleura. Thoracocentesis: Thoracocentesis allows the collection of samples of pleural fluid for analysis (including cytology and bacteriology); it can also be used in the treatment of pleuritis by allowing the drainage of large amounts of fluid. The precise site at which the chest is entered will vary depending on the amount of effusion; ultrasound guidance can be helpful. The usual site is either the right side at the 7th intercostal space, or the left side at the 7th or 8th spaces in the ventral third of the chest. Care must be taken to avoid the lateral thoracic vein, the liver, and the heart. The area is clipped and local anaesthetic infiltrated under the skin and into the intercostal muscles down to the pleura. A stab incision in the skin allows the introduction of a cannula (such as IV cannula, teat cannula or metal bitch urinary catheter) which is pushed into the pleural cavity along the cranial border of the rib (Figure 6.11). Fluid will normally drain by gravity, but care must be taken to avoid introduction of air into the cavity. Normal horses have a small quantity of clear, watery and pale straw-coloured fluid. The nucleated cell count of the fluid is low (<4 × 109/L) with approximately 70% neutrophils, 20% large mononuclear cells, and small numbers of lymphocytes and eosinophils. The total protein content is normally less than 30 g/L. Effusions are classified as transudates, modified transudates, exudates or chylous. • Transudates have normal characteristics and may be found in some early neoplastic diseases, congestive heart failure, hypoproteinaemia, etc. • Modified transudates are similar but with added cells (e.g. mesothelial cells, neutrophils or neoplastic cells) or protein. They are usually associated with neoplasia. • Exudates have high cell counts (>10 × 109/L) and high protein concentrations (>30 g/L). The majority of the cells are neutrophils. Exudates are usually thick and cloudy, and are seen in pleuritis/pleuropneumonia, and sometimes with neoplasia. • Chylous effusions are rare; they are milky white in appearance, and contain large numbers of lymphocytes. Pleuroscopy (thoracoscopy): Direct endoscopic examination of the pleural cavity is occasionally helpful in the evaluation of selected cases of pleuropneumonia, thoracic abscesses, pericarditis and thoracic neoplasia. It may also be helpful in aiding biopsy of pulmonary and pleural masses. Either rigid endoscopes (such as arthroscopes or laparoscopes) or flexible endoscopes may be used. Haematology: Haematological alterations in lower respiratory tract diseases are often minimal or non-specific. Hyperfibrinogenaemia, hyperglobulinaemia, hypoalbuminaemia and mild anaemia may be observed in infectious, inflammatory and neoplastic diseases. Table 6.1 Diagnostic features of lower respiratory tract disease Aetiology: RAO is strongly associated with stabling and feeding hay. In most cases, a pulmonary hypersensitivity associated with inhalation of organic dusts, primarily hay and straw dusts, occurs; this results in inflammation of the small airways. Hypersensitivity to fungal and thermophilic actinomycete spores (major component of hay and straw dust, especially from ‘heated’ bales) is involved in most cases. Spores of Faenia rectivirgula (formerly known as Micropolyspora faeni), Aspergillus fumigatus, etc., have been implicated. Recently it has also been suggested that RAO may result from non-specific inflammatory responses to inhaled pro-inflammatory agents, including moulds, endotoxin, particulates and noxious gases which are present in the breathing zone of stabled horses. Pathogenesis: Inhaled fungal and actinomycete spores (and other possible allergens) deposit in the bronchioles where specific hypersensitivity reactions are initiated. The net results of these reactions are: • Spasm of small airways (bronchospasm due to smooth muscle contraction). • Inflammatory bronchiolitis (Figure 6.12).

Lower respiratory tract

6.1 Diagnostic approach to lower respiratory tract diseases

6.2 Diagnostic features of the common lower respiratory tract diseases of the adult horse

Disease

Diagnostic features

RAO/SPAOPD/chronic lower airway inflammation

Endoscopy – lower airway exudate/bronchial inflammation

Tracheal aspirate – neutrophilia

BAL – neutrophilia

EIPH

Endoscopy – blood in airways

Tracheal aspirate/BAL – red blood cells and haemosiderophages

Radiography – opacity in dorsocaudal lung (advanced cases)

Lungworm

Endoscopy – larvae in bronchial tree

Tracheal aspirate – eosinophilia/larvae

BAL – eosinophilia

Neoplasia

Endoscopy – usually normal; rarely endobronchial mass

Tracheal aspirate/BAL – usually normal; rarely neoplastic cells

Radiography – pulmonary mass/pleural effusion

Ultrasound – pleural effusion/mass

Thoracocentesis – cytology may show neoplastic cells

Biopsy – diagnostic

Pleuroscopy – may show pleural mass

Pleuritis/pleuropneumonia

Endoscopy – lower airway exudate

Tracheal aspirate – neutrophilia; Gram stain/culture

BAL – may be normal or neutrophilia

Radiography – pulmonary consolidation/pleural effusion

Ultrasound – pleural effusion

Thoracocentesis – exudate; culture

Focal pneumonia/lung abscess

Endoscopy – lower airway exudate

Tracheal aspirate – neutrophilia; Gram stain/culture

BAL – may be normal

Radiography – pulmonary consolidation

Haematology – anaemia, hypoalbuminaemia, hyperfibrinogenaemia

Tracheal stenosis

Endoscopy – tracheal narrowing

Radiography – tracheal narrowing

Tracheobronchial foreign body

Endoscopy – foreign body

Tracheal aspirate – neutrophilia

Radiography – may be focal pulmonary consolidation

Chronic interstitial lung disease

Endoscopy – normal

Tracheal aspirate/BAL – neutrophilia/lymphocytosis

Radiography – miliary pulmonary infiltrate

Lung biopsy – diagnostic

6.3 Recurrent airway obstruction (RAO)