Chapter 10 Laryngoscopy and Tracheobronchoscopy of the Dog and Cat

Patient Restraint and Positioning

Injectable anesthetics are most typically used for laryngoscopy. My preference is propofol used to effect. The dose of propofol needed to generate a proper plane of anesthesia commonly ranges from 1 to 4 mg/kg IV. The drug should be given slowly, over 30 seconds to 2 minutes, to effect. Hypoxemia is absolutely predictable, and every patient should receive supplemental oxygen by mask before and immediately after the procedure. It is also appropriate to intermittently stop laryngoscopy to supplement the patient with oxygen, as needed. Atropine or glycopyrrolate should be used as a premedication to prevent bradyarrhythmias that are sometimes induced by laryngeal manipulation and subsequent vagal stimulation. Topical 1% lidocaine may occasionally be needed to decrease reflex responses (e.g., laryngospasm, swallowing, or gagging) that may be encountered during the procedure. This is much more commonly required in the feline species. Laryngoscopy should be performed with the patient in a sternal recumbent position. A mouth gag should be used to facilitate safe oral examination and to ensure good visualization of the larynx.

Procedure

Evaluation of Laryngeal Structure

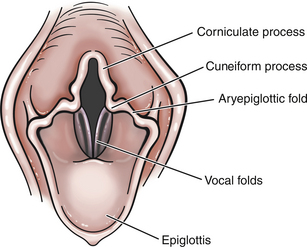

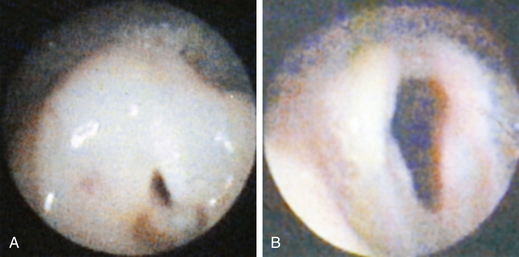

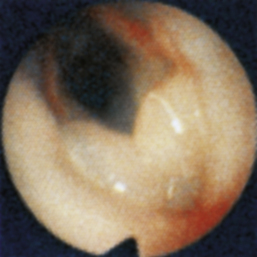

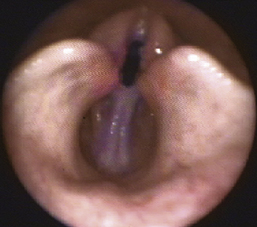

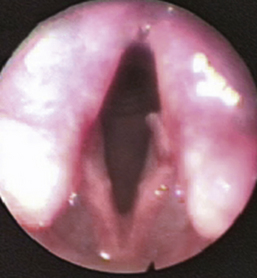

Normal structures that should be evaluated during laryngoscopy include the cricoid, thyroid, and arytenoid cartilages (also the corniculate and cuneiform processes), vestibular folds, vocal folds (cords), laryngeal saccules (lateral ventricles), epiglottis, and aryepiglottic folds (Figure 10-1). Normal mucosa should be pink in color, and superficial vessels may be visible. Secretions are minimal in the area of the normal laryngeal vault. Mucosal hyperemia and edema, excessive secretions, and redundant pharyngeal mucosa are commonly encountered abnormalities. If the lumen of the glottis is smaller than normal, the resulting airflow is turbulent rather than laminar. Turbulent airflow is irritating to mucosa, and this commonly causes at least some of the mucosal erythema and edema that is encountered during laryngoscopy.

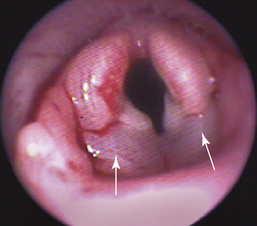

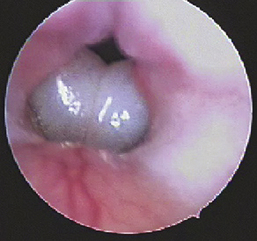

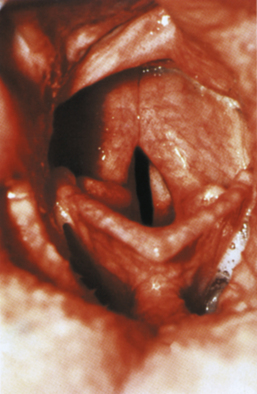

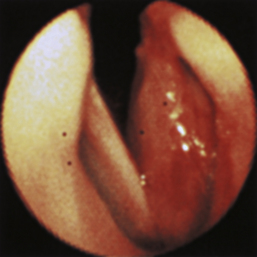

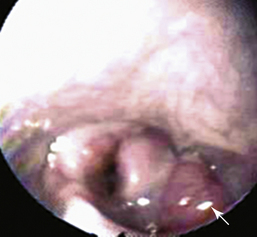

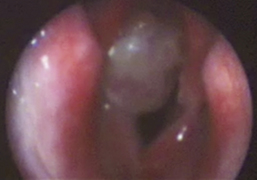

Common structural abnormalities include everted saccules and laryngeal collapse. These abnormalities usually develop as secondary phenomena as a result of more chronic disease and increased negative inspiratory pressures resulting from unilateral or bilateral laryngeal paresis or paralysis. Laryngeal webbing and granuloma formation both typically are secondary to previous surgery or trauma. Both conditions result in stenosis of the glottic lumen, and these fixed lesions often cause severe signs of airway obstruction. Less commonly a pharyngeal or laryngeal rannula, tumor, or foreign body may be found. (Laryngeal abnormalities are depicted in Figures 10-3 through 10-17 in the “Atlas” section). The physical characteristics of secretions or blood should be noted, and the examiner should attempt to determine the anatomic source of the abnormal fluid accumulation. The examiner should recall that secretions (including blood) found in the region of the larynx might have originated in the trachea, lower airways, or lung parenchyma.

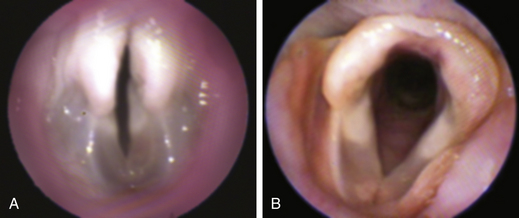

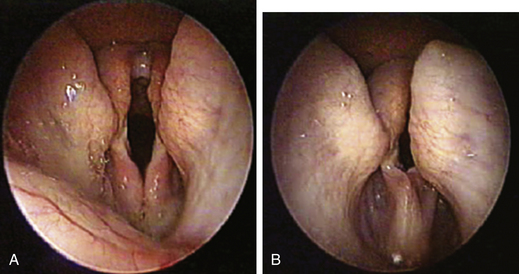

Evaluation of Laryngeal Motion

Laryngeal motion related to vocalization (e.g., whining) or swallowing should not be confused with laryngeal abduction. Normally the size of the glottic lumen is increased on inspiration by an active abduction of the arytenoid cartilages. Complete failure of one or both arytenoid cartilages to abduct (increasing the size of the glottic lumen) is defined as laryngeal paralysis (unilateral or bilateral). Partial failure of movement is referred to as laryngeal paresis. Paradoxical motion (the opposite side is pulled across the midline during inspiration) involving the vocal cord or entire arytenoid cartilage on the affected side is not usually a primary disorder. This is a form of laryngeal collapse and is generally a sequela of chronic laryngeal paresis or paralysis. Laryngeal collapse is a morbid finding because the success of surgery designed to permanently abduct one of the arytenoid cartilages (“lateralization”) is decreased; the “nonlateralized” cartilage and associated vocal fold will tend to move medially, and the glottic opening may not remain in even a semi-open position.

Ancillary Tools and Procedures

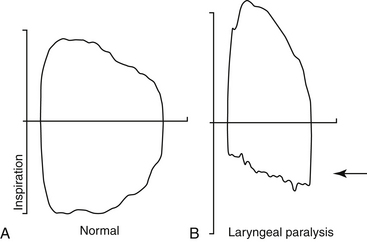

Radiographic evaluation of the larynx does not add significant diagnostic or prognostic information and is not routinely advocated as part of the complete evaluation of laryngeal disorders. A number of investigators have demonstrated that ultrasound of the larynx may be used to diagnose abnormal laryngeal structure or function. However, the practitioner will still need to directly visualize the larynx to make a proper diagnosis. Tidal breathing flow-volume loops (TBFVLs) have been used to document the presence of upper airway obstruction (Figure 10-2). However, an abnormal TBFVL still requires laryngoscopy to confirm the presence and extent of structural and functional laryngeal disorders. A laryngeal electromyogram or biopsy procedure may be used to delineate a specific cause, but these tests are properly performed after the initial laryngoscopic evaluation has been made.

Differences Between Feline and Canine Laryngoscopy

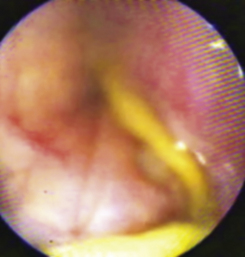

The laryngeal vault of dogs and cats are anatomically, grossly different. Specifically, the corniculate and cuneiform processes of the arytenoid cartilages are well developed and are much more prominent in dogs than in cats. Furthermore, mucosa lining the feline laryngeal vault becomes edematous after manipulations that cause no edema in canine patients. This edematous response may be dramatic and can result in serious airway obstruction (see Figure 10-5 in the “Atlas” section). The feline larynx may respond to light touch with spasm, further occluding the upper airway. For these reasons it is critical to place a few drops of 1% lidocaine on the surface of the feline laryngeal structures before laryngoscopy is performed. It is also important for the operator to be very gentle when manipulating this area.

Atlas for Laryngoscopy Pages 334-338

Figure 10-13 Laryngeal granuloma in a dog presented for noisy breathing 4 months after a “de-barking” surgical procedure.

Indications

The two most frequent indications for performing bronchoscopy in veterinary patients are (1) acute or chronic cough that is unanticipated or unresponsive to standard medical therapy and (2) unexplained radiographic infiltrates (Box 10-1). Bronchoscopy can also be invaluable in distinguishing cardiac from respiratory causes of a cough and for staging metastatic lung cancer. Tracheobronchoscopy should also be considered in veterinary patients with noisy breathing or stridor for which laryngoscopy fails to confirm the cause.

BOX 10-1 Indications for Tracheobronchoscopy

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree