Chapter 9 Lacrimal System

ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY

The lacrimal system consists of the following structures:

Lacrimal and Third Eyelid Glands

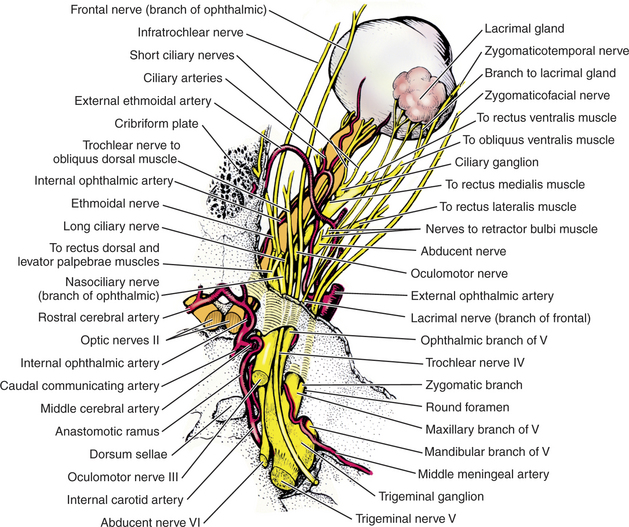

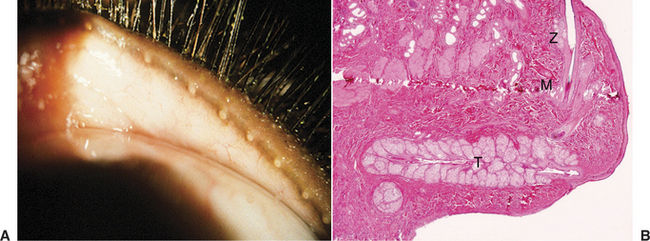

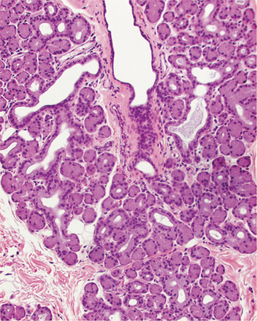

The gland of the third eyelid, which lies within the stroma of the third eyelid, is partially visible on the inner surface of the third eyelid (see Chapter 8 and Figure 9-2). The tubuloalveolar lacrimal gland is flattened and lies over the superior-temporal part of the globe. In the dog it lies beneath the orbital ligament and supraorbital process of the frontal bone and is related to the medial surface of the zygomatic bone (Figure 9-3). The position is similar in species with a fully enclosed bony orbit.

Figure 9-2 Tubuloalveolar structure of the canine gland of the third eyelid.

(Courtesy Dr. Richard R. Dubielzig.)

Accessory Lacrimal Glands

The accessory lacrimal glands (Figure 9-4), which are near the lid margins and contribute to the precorneal tear film, are composed of the following:

Precorneal Tear Film

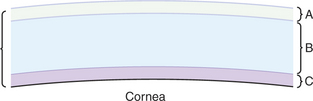

The precorneal tear film covers the cornea and conjunctiva (Figure 9-5). It consists of three layers, differing in composition, and is about 8 to 9 μm thick.

Figure 9-5 Precorneal tear film. A, Superficial lipid layer; B, aqueous layer; C, inner mucoid layer.

The inner mucoid layer (1.0 to 2.0 μm thick) consists of hydrated glycoproteins derived from the conjunctival goblet cells. This layer is critical in binding the lipophobic aqueous layer to the lipophilic corneal surface and in preventing the tear film from “beading up” on the corneal surface much like water does on the surface of a freshly waxed car. The mucoprotein molecules are thought to be bipolar, with one end lipophilic (associated with the corneal epithelium) and one end hydrophilic (associated with the aqueous layer). This layer is also difficult to appreciate clinically but may be indirectly evaluated by determination of the tear film break-up time (TFBUT).

Lacrimal Puncta, Canaliculi, and Nasolacrimal Duct

In most domestic mammals the inferior and superior puncta lie on the inner conjunctival surface of the eyelids, near the nasal limit of the tarsal glands (see Figure 9-1). Rabbits possess only one large inferior puncta that is a few millimeters from the eyelid margin.

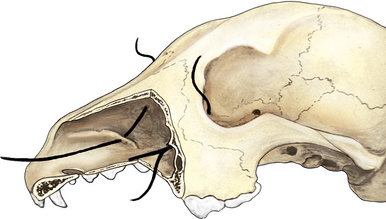

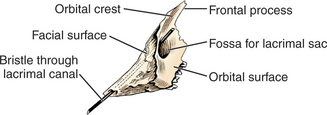

The lacrimal canaliculi (superior and inferior) lead to a variable dilation in the common nasolacrimal duct—the lacrimal sac. The lacrimal sac varies in size, in some animals consisting only of a slight dilation in the duct. The sac lies within a depression in the lacrimal bone called the lacrimal fossa (Figure 9-6).

Figure 9-6 Left canine lacrimal bone, lateral aspect, showing the lacrimal fossa.

(Modified from Evans HE 1993]: Miller’s Anatomy of the Dog, 3rd ed. Saunders, Philadelphia.)

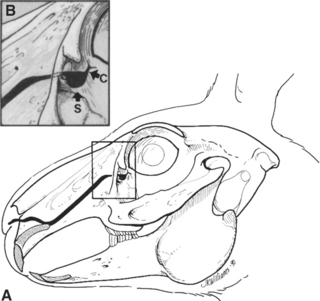

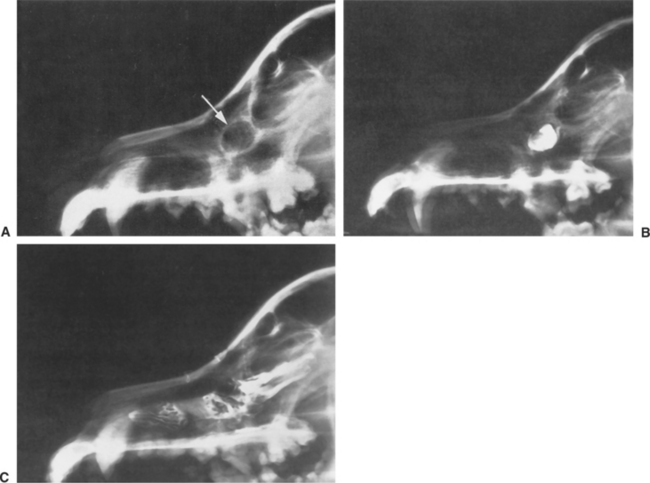

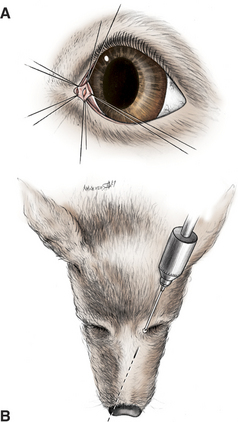

From the lacrimal sac, the nasolacrimal duct passes via a canal on the medial surface of the maxilla to open in the nasal cavity (Figure 9-7). In dogs the opening is ventrolateral near the attached margin of the alar fold; in horses it is ventral on the mucocutaneous junction; and in cattle it is more lateral. In cattle and horses the nasal opening is readily visible and can be cannulated, but in dogs it can be seen only after exposure with a speculum or other suitable instrument with the animals under general anesthesia. In dogs the nasolacrimal duct commonly has an opening into the nasal cavity between the lacrimal sac and the nasal opening, although the remainder of the duct is intact. In rabbits the nasolacrimal duct has multiple sharp bends and constricted areas, which may be associated with the frequency of duct obstruction and dacryocystitis in this species. Cannulation is also difficult in most rabbits (Figure 9-8).

DISTURBANCES OF LACRIMAL FUNCTION

The two categories of lacrimal dysfunction are as follows:

Effects of Precorneal Tear Film Dysfunction

Examination

The techniques for examination of lacrimal disorders have been discussed in Chapter 5. The reader is referred to that chapter for descriptions of the following specific tests:

The fluorescein passage test (Jones test) is reliable only when its result is positive. Because of communications between the nasolacrimal duct and the nasal cavity, false-negative results occur even though the duct is patent. If epiphora is due to overproduction of tears, the eye is usually red and the STT values are higher than normal.

Disorders Characterized by Epiphora

Dacryocystitis

Dacryocystitis is inflammation within the lacrimal sac and nasolacrimal duct. It occurs most frequently in dogs and cats and less frequently in horses. Although foreign bodies (e.g., grass awns, sand, dirt, and concretions of mucopurulent material) can be expressed in some patients, the primary cause is often undetermined. Cystic dilations of the nasolacrimal duct causing chronic dacryocystitis in dogs have been described. They are treated by creation of a drainage stoma into the nasal cavity (Figure 9-9). The infected focus within the proximal portion of the duct may reinfect the conjunctival sac, resulting in chronic, unilateral conjunctivitis of apparent unexplained cause. Often the amount of ocular discharge in dacryocystitis is far in excess of what would be expected in view of the severity of conjunctivitis present.

CLINICAL SIGNS.

The clinical signs of dacryocystitis are as follows:

TREATMENT

Nasolacrimal Catheterization.

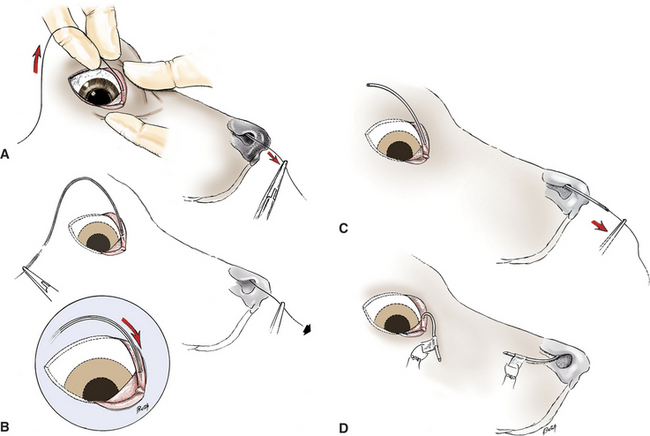

Because of its tendency to recur, definitive surgical catheterization (Figure 9-10) is indicated for dacryocystitis. Although daily flushing and topical medication are effective in some cases, they are less reliable than catheterization and there is a greater chance of recurrence. The tube is left in place for 2 to 3 weeks. The inserted tubes rarely cause discomfort unless they become loose. For the first few days the uncannulated punctum may be flushed daily with a topical ophthalmic antibiotic solution, and topical antibiotic/corticosteroid solution is also applied to the ocular surface. If abscessation of the sac or severe dermatitis is present, systemic antibiotics are added.

Dacryocystotomy.

For patients in which obstruction prevents the passage of a catheter, the lacrimal sac may be exposed ab externo, through an incision parallel to the lower lid, followed by removal of the outer surface of the lacrimal bone with a Hall Surgitome bur over the sac, flushing of the sac, and placement of the catheter (Figure 9-11). In some chronically affected animals a cavity may develop in the region of the sac. If the catheter is left in place and antibiotic therapy is continued, the space usually fills with fibrous tissue and a patent duct remains. This may take several months.

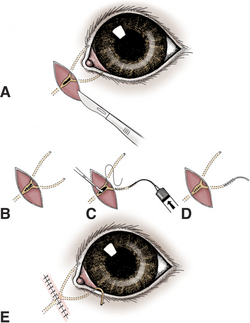

Congenital Atresia, Ectopia, and Imperforate Puncta

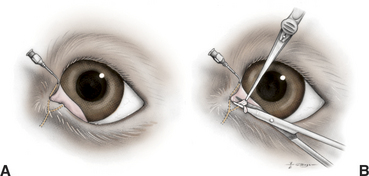

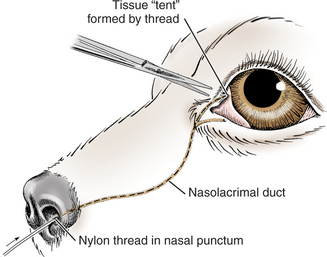

In dogs, imperforate puncta (usually of the inferior puncta) and punctal aplasia are common, especially in American cocker spaniels, Bedlington terriers, golden retrievers, miniature and toy poodles, and Samoyeds. The condition is congenital and is often characterized by epiphora, although some animals are relatively asymptomatic and epiphora may not become apparent until several weeks of age, when tear production increases. Diagnosis is made by examination of the normal location of the puncta with magnification and from the inability to cannulate or probe the puncta with a small polytetrafluoroethylene (Teflon) IV catheter (minus needle), a lacrimal cannula, or fine nylon thread. In most cases the obstruction consists of a layer of conjunctiva over the lumen, but occasionally obstructions are present in other parts of the nasolacrimal duct. The overlying conjunctiva may be removed with fine scissors after it is elevated with liquid under pressure (Figure 9-12) or through retrograde probing with fine nylon thread (2/0) from the nasal opening (Figure 9-13). Some patients require short-term (1 to 3 weeks) placement of an indwelling catheter to prevent fibrosis of the newly created stoma, especially if the wound bleeds after excision.

Cicatricial Nasolacrimal Obstructions

In cats, especially kittens, scarring and blockage of the puncta or nasolacrimal ducts are common sequela of presumed herpetic keratoconjunctivitis and upper respiratory tract infections. Similar changes due to variety of causes may be seen in any species and frequently accompanies symblepharon. If the puncta and ducts cannot be cannulated, conjunctivorhinostomy or drainage procedures to the oral cavity (conjunctivobuccostomy) are the only remedy. Conjunctivorhinostomy and conjunctivobuccostomy are usually performed by a veterinary ophthalmologist in animals without evidence of active conjunctivitis or chronic respiratory disease. Active, or recurrent, disease increases the chance the newly created opening will scar closed and usually means that surgery will fail to correct the problem. If recurrent respiratory disease is present in cats, a careful examination for evidence of herpetic keratitis is performed and serologic tests for feline leukemia virus, feline immunodeficiency virus, and possibly cryptococcosis should be considered.

CONJUNCTIVORHINOSTOMY.

In conjunctivorhinostomy a communication is made from the medial conjunctival sac to the nasal cavity and is kept open with a stent of plastic or silicone tubing until healed (Figure 9-14). The method is most suitable for dogs lacking lacrimal drainage but can be used in cats. In cats the opening tends to become obstructed with scar tissue, and the stent is left in longer (8 to 12 weeks) before initial removal. During the postoperative period the topical antibiotic therapy is continued and the stent is cleaned frequently. Also, the eye is checked weekly to ensure that the stent is not causing ocular irritation (e.g., by pressing on the cornea through the third eyelid).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree