2 Laboratory tests

INTRODUCTION

There are measures that the clinician can take to minimize the incidence of false-positive and false-negative test results. Firstly, take full histories and perform full physical and dermatological examinations and draw up a differential diagnosis (see Chapter 1). Whilst it is important to perform basic screening tests such as skin scrapes and cytology, diagnostic tests used should as far as possible be targeted to the diseases on the differential diagnosis list. The indiscriminate use of a wide variety of diagnostic tests will increase the likelihood of false-positive and false-negative test results. It is a common mistake to assume that because skin lesions look severe, autoimmune disease is involved. Statistically, the low prevalence of rare diseases will increase the chance of a false-positive test result, leading to an erroneous diagnosis. Much more frequently, severe skin lesions are just an unusual manifestation of a common disease.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTS FOR ECTOPARASITISM

Ectoparasitic diseases encountered in small animal practice are shown in Table 2.1. The tests available for the detection of external parasites are combings and coat brushings, the use of acetate strips, skin scrapes, hair plucks, a scabies IgG ELISA test and histopathological examination.

Table 2.1 Ectoparasites encountered in small animal practice

| Insects | |

| Flea infestation | Common |

| Lice | Uncommon |

| Mites | |

| Sarcoptes scabiei | Common |

| Notoedres cati | Rare in cats |

| Cheyletiella spp. | Common |

| Otodectes cynotis | Common |

| Neotrombicula autumnalis | Common |

| Demodex spp. | Common |

| Endoparasites | |

| Pelodera, hookworms | Uncommon to rare |

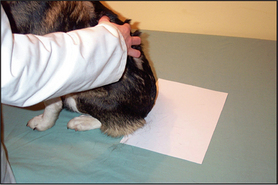

Coat brushing examination

This is a useful and moderately sensitive test for the diagnosis of surface and superficial parasites such as fleas, lice, harvest mites and Cheyletiella spp. mites. Scale is dislodged from the dorsal trunk (Fig. 2.1) onto a piece of A4 paper by combing or vigorous brushing with the fingertips. The paper is folded and tapped so that the material collected falls into the crease. Hair is removed and the material can be examined grossly for the presence of flea faeces, as well as larger parasites such as lice. The material should be collected onto clear adhesive tape, mounted onto a glass slide and examined under the low-power light microscope. The complete area under the adhesive tape should be carefully examined.

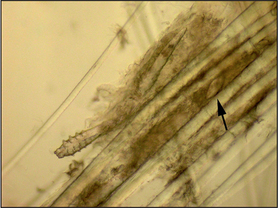

Hair plucks

Microscopic examination of hair plucks may be useful to detect Demodex spp. mites (Fig. 2.2) and Cheyletiella spp. or louse eggs. Hair plucks are very useful when taking samples from areas that are difficult to scrape, such as the feet in the case of pododemodicosis, when skin scraping would require sedation. Fifty to 100 hairs are plucked and mounted in liquid paraffin on a glass slide under a coverslip. The hair tips, shafts and bulbs should all be carefully examined. One study showed deep skin scraping to be more sensitive than hair plucks in cases of localized and squamous demodicosis, and therefore demodicosis should not be ruled out on the basis of not finding mites on hair plucks.

Skin scrapings

Hair should be clipped with a No. 40 clipper blade. When scraping for Demodex spp., it helps to gently squeeze the skin between thumb and forefinger, as this extrudes mites from the hair follicles. A small amount of liquid paraffin to suspend collected material (or water if using potassium hydroxide) is applied to the area to be scraped. A blunted No. 10 scalpel blade is used to scrape material from the skin surface. Deep skin scrapes resulting in capillary oozing should be made when looking for Sarcoptes or Demodex spp. mites (Fig. 2.3). Collected material is mounted onto a glass slide in liquid paraffin or potassium hydroxide. A coverslip should be applied. Examine samples for ectoparasites under the low-power objective and scan the entire area under the coverslip.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTS FOR DERMATOPHYTOSIS

Techniques available for diagnosis include:

Wood’s lamp: Wood’s lamp is an ultraviolet light with a wavelength of 360 nm. Only lamps with two bulbs and a magnifier should be used. It is important to switch the lamp on and allow it to warm up for 5 minutes prior to examination. Examination of the animal should be conducted in a darkened room. Hair shafts infected with certain strains of Microsporum canis fluoresce an apple green colour under Wood’s lamp examination due to tryptophan metabolites. Wood’s lamp examination is a test with high specificity (100% in the right hands) but low sensitivity, as only 50% of strains of Microsporum canis fluoresce. Rare infections with M. audounii, M. distortum and Trichophyton schoenlenii may also result in fluorescence.

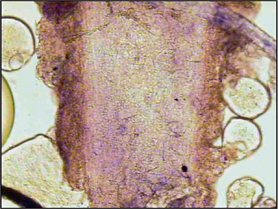

Direct microscopy: Most dermatophytosis cases in domestic animals involve ectothrix invasion of hair shafts by fungal spores which can be visualized under ×40 magnification using the light microscope. Fluorescing hairs or hairs from lesions may be plucked for direct microscopic examination. Samples should be mounted on the slide in liquid paraffin or potassium hydroxide. Hair shafts with distorted or damaged cuticles should be examined under higher power for the presence of fungal spores (Fig. 2.4). Although a test with high specificity in the right hands, this is not a sensitive technique for the diagnosis of dermatophytosis in the hands of the inexperienced clinician.

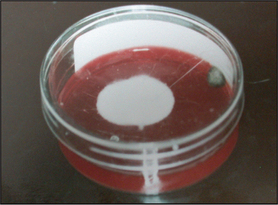

Dermatophyte test medium (DTM) is used as an in-practice growth medium for the diagnosis of dermatophytosis. DTM is Sabouraud’s dextrose agar with various antimicrobials that suppress bacterial and some saprophytic fungal growth, along with phenol red as an indicator. Dermatophytes metabolize protein in the medium first, giving off alkaline metabolites which turn the pH indicator red (Fig. 2.5). This should happen within 10 days and should occur as the fungal colony grows. Saprophytic species of fungi metabolize carbohydrates first and the red colour change should only appear after 10 or more days and subsequent to colony growth. There are potential problems associated with the use of DTM. The agar should be inspected daily for evidence of fungal growth and colour change; some saprophytic species of fungi can induce a colour change within 10 days and Microsporum persicolor may produce a colour change after 10 days. Thus, the identity of any fungal mycelium should be confirmed by microscopic examination, which requires specialist knowledge. Furthermore, DTM may not be a suitable growth medium for the identification of some fungi that will only sporulate on Sabouraud’s dextrose agar. Nevertheless, DTM culture remains a useful in-practice tool for screening for dermatophytosis, but the clinician should be aware of the limitations.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree