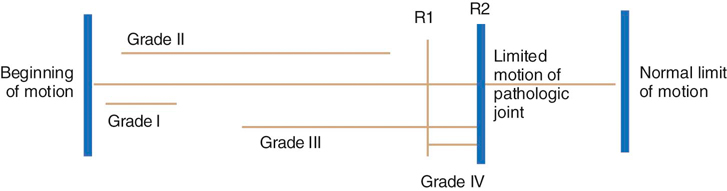

Manual therapy techniques are skilled hand movements intended to improve tissue extensibility, increase range of motion (ROM), induce relaxation, mobilize or manipulate soft tissue and joints, modulate pain, and reduce soft tissue swelling, inflammation, or restriction.1 The primary techniques included in manual therapy are mobilization and manipulation of joints and associated soft tissues. Mobilizations are passive movements that are either oscillatory or sustained stretch performed in such a manner that the patient can prevent the motion if so desired. These motions are performed anywhere within the available ROM. The intent of this chapter is to provide an overview of the principles of manual therapy, followed by selected treatment techniques for the hip, stifle, elbow, shoulder, carpus, and the thoracic and lumbar spine. The techniques of GD Maitland,2,3 an Australian physical therapist who developed a clinically based approach in the 1960s and 1970s, are emphasized in this chapter. Maitland described four grades of mobilization (I-IV) (Figure 26-1) and manipulation. Manipulation, a grade V mobilization, is a high velocity, low amplitude passive movement that cannot be prevented by the patient and is typically performed near the end of the available ROM. There have been numerous randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in humans that have demonstrated the efficacy of manual therapy for treating patients with a variety of disorders in the spine and peripheral joints. Many of these studies have compared “traditional treatments,” such as exercise, pharmaceutical interventions, rest, and placebo, with manual therapy. Other RCTs have compared these traditional forms of therapy to groups receiving both the traditional therapies plus manual therapy. The majority of these studies have found that manual therapy is as effective if not superior to traditional therapies.4–15 Common outcome measures assessed have been pain, functional scales, disability levels, ROM, number of treatments needed, length of time in treatment, and cost effectiveness of treatment. Despite the growing body of evidence for manual therapy, it is viewed as a complementary therapy in human medicine by many, even though its effectiveness seems well substantiated and the risks are low. The most likely reason for its slow acceptance is that the skill level required to properly apply these techniques is higher than with traditional therapies such as exercise or modalities. Rationales for the reasons manual therapies may work have been investigated and include reducing muscle inhibition,16 decreasing pain,17,18 improving intervertebral disk hydration,19 correcting joint displacement, adjusting joint subluxations, restoring bony alignment, reducing nuclear protrusion,20,21 and placebo effect.8 More recent theories include evidence supporting the need for adequate stresses and normal movement as being critical to maintain the integrity of collagenous tissues, muscles, and bones.22 Evidence of the effectiveness of manual therapy must be established in small animals. Although many anatomic similarities exist between humans and small animals, we cannot assume the techniques will yield the same results. The list of contraindications presented by Dutton23 includes spinal instability, bacterial infection, malignancy, systemic localized infections, sutures over the area, recent fracture, cellulitis, febrile state, hematoma, acute circulatory condition, an open wound at the treatment site, osteomyelitis, advanced diabetes, hypersensitivity of the skin, inappropriate end feel (spasm, empty, bony), constant severe pain, extensive radiation of pain, pain unrelieved by rest, any undiagnosed lesion, and severe irritability (pain that is easily provoked, and that does not go away within a few hours). Additional contraindications specific to dogs include contractures such as fibrotic myopathy and quadriceps contracture, or in other circumstances in which manual therapy is unlikely to effect any change and may be painful. An overly aggressive or fearful dog that may bite the therapist or unrelaxed dogs are also contraindications. Total elbow and hip replacements should be considered a contraindication for grades III-V accessory mobilizations until the appropriateness of joint mobilization techniques are further evaluated for these procedures. Precautions (proceed with caution) identified by Dutton23 include joint effusion or inflammation, rheumatoid arthritis, presence of neurologic signs, osteoporosis, hypermobility, pregnancy (if the technique is to be applied to the spine), and steroid or anticoagulant therapy. There are a number of approaches to manual therapy, including those developed by physicians24–26 and by physical therapists.2,3,27–29 Regardless of the approach, there are several principles that should be considered as the patient is examined and treated. Maitland stresses the importance of communicating with the patient to fully “understand what the patient is enduring.”2 Of course, in the case of animals, the examiner must communicate with two constituents—the dog and the owner. Body postures, pain patterns, and respiratory patterns should be closely monitored in the patient. Maitland states, “During examination and assessment, pain should never be considered without relation to range nor range without relation to pain.”2 Depending on the nature of the injury or disease, joints are affected by the presence of pain and stiffness. If pain is the primary problem, it may limit motion, as in hip dysplasia. When the pain diminishes, the ROM may improve. If the primary problem is joint dysfunction or stiffness, pain will be most evident at or near the end of available ROM. As the available ROM increases, pain will be less of a factor. In those cases in which both pain and loss of motion occur simultaneously, the examiner must decide which is the primary problem. These relationships are the basis of deciding which grade of passive movement and other therapies should be used to treat the problem. The dog exhibits a capsular pattern if the entire capsule of the joint is inflamed or involved. Cyriax24 described a capsular pattern as a joint-specific pattern of loss of motion with arthritis. These have not been described for dogs, but limitations in movement accompany certain disorders. An example is that hip extension and hip abduction are typically the most limited motions in a dog with hip dysplasia. End feel is the sensation imparted to the examiner when the end of passive ROM is encountered. The passive motion must be performed with a relatively quick movement and the end of range is bumped briskly. Cyriax24 described the quality of normal and abnormal end feels, which are defined in Table 26-1. Table 26-1 Joint End Feel Characteristics The therapist participates in three activities while managing a patient problem: examination, treatment, and assessment. Although each is important to the provision of a complete and quality program, assessment is the keystone. Assessment involves “open-mindedness, mental agility and mental discipline, linked with a logical and methodical process of assessing cause and effect.”2 The therapist is thinking and assessing to make certain that the right task is being performed and that the task is being performed correctly. The therapist must continually assess the decision-making process during examination and treatment procedures. Assessment is implemented at three points of the patient interaction. The first assessment is implemented during the initial examination of the patient, making certain that clinical signs are examined and evaluated to reach the best diagnosis and formulate an appropriate plan of care. The second assessment occurs during the treatment session. The therapist assesses the appropriateness of the treatment techniques while the patient response is evaluated. The third assessment is an analytic process to consider the entire treatment program to determine whether the patient is progressing as a result of the treatment and to determine the prognosis for resolution of the current problem. Joint mobilization should be planned with a specific grade of mobilization in mind. Grades are assigned to the mobilizations depending on the range through which the mobilization is applied and the point in the range where it is applied. Figure 26-1 shows a modification of Maitland’s graded mobilizations.2 When ROM is decreased due to pain: • If the pain is treated, then ROM should increase. • Grade I and II mobilizations should be performed. • Grade I and II mobilizations should be performed in the pain-free range for 30 seconds or longer. Function should be assessed after mobilization to determine whether any change has been achieved. When ROM is decreased due to stiffness: • Grade III and IV mobilizations should be used. • Grade III and IV mobilizations should be performed in the direction of the stiffness for 60 seconds if possible. Function should be assessed after mobilization to determine whether any change has been achieved. • If pain occurs before resistance, use techniques to control the pain before progressing to more aggressive treatment. • If pain occurs with resistance, mobilizations may be used with caution. However, it is customary to treat the pain and then the stiffness. • If pain occurs after the resistance, vigorous mobilization may be used to treat the stiffness followed by techniques for pain. There are two types of mobilizations: • Physiologic mobilizations are done in the same pattern of movement that is produced by voluntary muscle contraction. • Accessory mobilizations are performed in a pattern of movement that must be done passively and cannot be produced by voluntary muscle contraction. These should be done in the midrange of the joint motion (open pack position) because this allows for more joint play or motion. There are additional guidelines to help the therapist decide which type of mobilization to perform. • If pain is being treated and physiologic mobilization grades I and II cause pain, then accessory grades I and II should be performed. • If 50% of physiologic active ROM is not available secondary to pain, then use accessory grades I and II to treat the pain (50/50 rule). • If treating stiffness (Grades III and IV), the therapist should perform 60 seconds of an accessory mobilization followed by 60 seconds of a physiologic mobilization and then assess the effect. During any mobilization treatment, an assessment should be made after each set of oscillations, whether for pain or stiffness, to determine the effect of the mobilization. This sequence should be performed three times. Mobilization for joint restrictions should be oscillations. Mobilization for muscle, tendon, and skin restrictions should be sustained. Repetitive low-intensity stretches are beneficial to stimulate tissue elongation. Contracted tissues respond positively to sustained stretch.30 Dutton defines open kinetic chain activities as when the “involved end segment of an extremity [is] moving freely through space, resulting in isolated movement of a joint.”23 Examples of an open kinetic chain activity in a dog include when a paw is swinging forward in the gait cycle or when the dog is moving a forelimb while in lateral recumbency. On the other hand, closed kinetic chain activity occurs when the distal segment of an extremity is in contact with a surface and the limb is weight bearing.28 Examples of a closed kinetic chain activity include the stance phase of gait. It is of value to note whether a limb is being exercised in the open versus closed kinetic chain. Closed kinetic chain activities facilitate proprioception, muscles working in groups, and coordination of joint function. On the other hand, it is easier to achieve isolated joint motion in the open kinetic chain. The shoulder, or glenohumeral joint, is a ball-and-socket joint and follows the convex on concave rule of motion (Box 26-1). Impairment of shoulder ROM may be seen after a fracture of the humerus, bicipital tenosynovitis, osteochondritis dissecans, infraspinatus contracture, scapular fracture, surgical repair of shoulder instability, and other conditions. Compensations in the shoulder complex may also be seen as a result of hindlimb or spinal problems such as intervertebral disk disease, canine hip dysplasia, cruciate disease, or neurologic problems. It is believed that dogs increase the amount of weight placed on their forelimbs to compensate for a problem affecting the spine or hindlimb. Over time, problems may develop in the forelimbs secondary to the increased forces placed on the joint.

Joint Mobilization

Contraindications and Precautions for Manual Therapy

Basic Principles of Manual Therapy

Relationship of Pain and Range of Motion

Name

Description

Example

Bony or hard

Bone approximates bone, resulting in an abrupt, hard stop.

Loss of flexion with end-stage elbow osteoarthritis; loss of stifle motion as a result of quadriceps contracture following fracture of the distal femoral physis

Soft tissue approximation

Motion is stopped by compression of soft tissues. Abnormal if occurs too early in the range as the result of edema.

Normal stifle flexion

Capsular or firm

A firm but slightly yielding stop occurs as a result of tension in the joint capsule or ligaments. Abnormal if occurs too early in the ROM.

Normal carpal extension

Springy block

A rebound is felt at the limit of motion—motion stops and then rebounds. Abnormal; may indicate joint effusion or a joint mouse.

Entrapped torn medial meniscus.

Empty

No end point is felt because the patient stops the motion because of pain; no resistance felt. Abnormal; indicates presence of sharp pain.

Sciatic nerve entrapment as a result of a migrating intramedullary pin; fracture of the lateral humeral condyle

Assessment

The Clinical Environment

Treatment with Mobilization

Grades

How to Choose the Appropriate Mobilization Grade

Oscillation versus Sustained Stretch

Open versus Closed Kinetic Chain

The Shoulder Joint

Lateral Distraction of the Glenohumeral Joint (Figure 26-2)

Figure 26-2 Lateral distraction of the glenohumeral joint. The arrow indicates the direction of the mobilization.![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Joint Mobilization

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue