Chapter 44 Introduction to Veterinary Mycology

Fungal diseases of nonhumans were reported nearly two centuries ago, and among the first was infection by Beauveria bassiana, a fungal pathogen of silkworms that nearly destroyed the Chinese silk industry in the early nineteenth century. After many decades of relative neglect, modern veterinary mycology has become part of the mainstream of veterinary microbiology. Frequency of diagnosis of mycoses in domestic animals has increased in concert with the pattern in human medicine. This is partly because of advances in veterinary oncology, in which immunosuppressive treatments predispose to fungal infection. In addition, the increased number of effective antifungal agents for use in animals has increased interest in detection, identification, and characterization of animal-associated fungi.

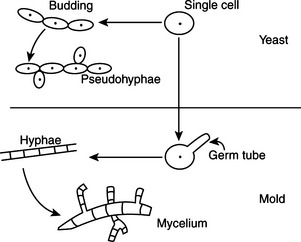

Fungi are unicellular or multicellular chemoheterotrophic eukaryotes. Their cell walls contain cellulose, chitin, glucan, chitosan, and/or mannan. For practical purposes they may be grouped into yeasts, molds, and fungal-like agents. Yeasts are oval to spherical single cells; they reproduce by budding, a phenomenon in which a progenitor cell pinches off part of itself to produce another identical cell. Molds are multicellular filamentous fungi that consist of masses of threadlike filaments called hyphae that grow by elongation of their tips into an intertwining mat called the mycelium (Figure 44-1). Fungal-like agents, as exemplified by Prototheca and Pythium species, have traditionally been discussed with mycotic agents because they produce elements that resemble fungi in tissue, and some may form yeastlike colonies on mycologic media.

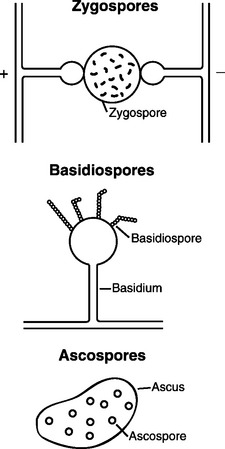

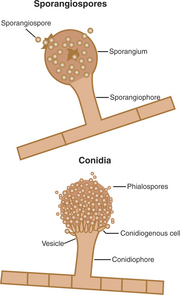

The individual reproductive bodies of fungi are called spores. During the evolutionary process, most fungi relied on a combination of asexual and sexual reproduction for survival. Asexual spores are produced by mitosis. The two main types of asexual spores are sporangiospores and conidia (Figure 44-2). Many of the lower fungi of the class Zygomycetes produce sporangiospores that are contained in a closed structure called the sporangium. Conidia are naked spores borne on hyphae and produced by fungi such as Aspergillus and Penicillium spp. Sexual spores are produced through fusion of the protoplasm and nuclei of two cells by meiosis, and include ascospores, basidiospores, and zygospores (Figure 44-3). Sexual spores and the protective structures that surround them serve as the basis for fungal classification.

FIGURE 44-2 Sporangiospores and conidia, the two main types of asexual spores.

(Courtesy Ashley E. Harmon.)

Pathogenic fungi are categorized into four groups based on sexual reproduction, even if sexual reproduction has not been observed. These groups correspond to phyla within the kingdom Fungi and comprise the ascomycetes, basidiomycetes, zygomycetes, and deuteromycetes (fungi imperfecti). The first three groups produce sexual spores, but the deuteromycetes are “imperfect,”in that they have no known sexual state. The genera comprising the deuteromycetes are called “form” genera, because they are characterized without the use of sexual structures. Taxonomy of the veterinary pathogenic fungi is presented in Table 44-1.

TABLE 44-1 Taxonomy of the Veterinary Pathogenic Fungi

| Taxonomic Designation | Representative Genera | Veterinary Disease |

|---|---|---|

| Phylum Zygomycota, Class Zygomycetes | ||

| Order Mucorales | Absidia, Mucor, Rhizopus | Abortion, zygomycosis |

| Order Entomophthorales | Basidiobolus, Conidiobolus | Nasal infection, zygomycosis |

| Phylum Ascomycota, Class Ascomycetes | ||

| Order Saccharomycetales | Pichia (teleomorphs of some Candida spp.) | Numerous mycoses |

| Order Onygenales | Arthroderma (teleomorphs of dermatophytes) | Ringworm |

| Order Eurotiales | Teleomorphs of some Aspergillus spp. | Aspergillosis |

| Order Microascales | Pseudoallescheria boydii (teleomorph of Scedosporium apiospermum) | Mycetoma |

| Order Pyrenomycetes | Gibberella (teleomorph of some Fusarium spp.) | Mycotic keratitis |

| Phylum Basidiomycota, Class Basidiomycetes | ||

| Order Tremellales | Filobasidiella (teleomorph of Cryptococcus neoformans) | Cryptococcosis |

| Phylum Deuteromycota, Class Deuteromycetes | ||

| Order Cryptococcales | Candida, Cryptococcus, Malassezia, Trichosporon | Numerous mycoses |

| ORDER MONILIALES | ||

| Family Moniciliaceae | Aspergillus, Coccidioides, Sporothrix | Numerous mycoses |

| Family Dematiaceae | Alternaria, Bipolaris, Cladosporium, Curvularia, Exophiala | Chromoblastomycosis, mycetoma, nasal granuloma, phaeohyphomycosis |

Mycology is often descriptive, and the importance of morphology in the identification process mitigates in favor of a clear understanding of mycologic terminology (Table 44-2). The mycelial mat is known as the thallus, but this term is specifically reserved for colonial growth that arises from a single spore. Some of the medically significant fungi, such as Histoplasma capsulatum and Blastomyces dermatitidis, are dimorphic, in that they can exist in either the yeast or mold form; yeast forms are present at 37° C and the mold form is present at 25° C. Dematiaceous fungi are dark colored, containing melanin in hyphal or conidial cell walls. Dermatophytes invade hair, nails, and claws.

TABLE 44-2 Glossary of Mycologic Terminology

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Aerial hyphae | Hyphae that develop above the agar surface |

| Anamorph | Asexual form of a conidial fungus |

| Annelide | Cell that produces conidia; as the conidium is released, a ring of cell wall material is formed |

| Anthropophilic | Fungi that almost exclusively infect humans; examples are Epidermophyton floccosum and Trichophyton rubrum |

| Arthrospore | Asexual spore produced by fragmentation of existing hypha into separate cells; examples are Coccidioides immitis and Geotrichum candidum |

| Ascospore | Sexual spore produced in a saclike structure (ascus), characteristic of true yeasts |

| Ascus | Round saclike structure that contains ascospores |

| Asexual | Reproduction by division or redistribution of nuclei but without nuclear fusion |

| Basidiospore | Sexual spore formed on the basidium |

| Blastoconidium | Blastospore; conidium formed by budding along hypha, pseudohypha, or single cell; examples are Candida albicans and Cryptococcus neoformans |

| Budding | Process of asexual reproduction in which new cells develop as outgrowths of the parent cell; examples are yeasts |

| Capsule | Colorless, mucopolysaccharide sheath on the cell wall; example is Cryptococcus neoformans |

| Chlamydospore | Thick-walled resistant cell formed as a result of enlargement of an existing hyphal cell; examples are Histoplasma capsulatum and Candida albicans |

| Chromoblastomycosis | Chronic fungal infection characterized by nodular, cutaneous lesions; contain dark brown sclerotic bodies when examined microscopically |

| Clavate | Club shaped; examples are macroconidia of Microsporum nanum |

| Cleistothecium | Closed, round structure in which asci and ascospores are held until their release; example is Pseudallescheria boydii |

| Columella | Swollen tip of sporangiospore projecting into sporangium in some Mucorales; examples are Rhizopus and Mucor spp. |

| Conidiophore | Specialized hypha or cell on which conidia are produced; examples are Aspergillus and Penicillium spp. |

| Conidium | Asexual spore; examples are Aspergillus and Penicillium spp. |

| Dematiaceous | Fungi that possess dark hyphae; examples are Sporothrix schenckii and Ochroconis (Dactylaria) gallopava |

| Dermatophtye | Member of genus Microsporum, Trichophyton, or Epidermophtyon; infects hair, skin, or nails |

| Dichotomous | Division of hyphae into two equal branches of same diameter as original hypha; examples are Aspergillus spp. |

| Dimorphic | Fungi that exist in yeast and mycelial forms; examples are Blastomyces dermatitidis and Histoplasma capsulatum |

| Echinulate | Spiny; examples are macroconidia of Microsporum spp. |

| Ectothrix | Arthrospores located on outermost portion of hair shaft; examples are Microsporum spp. |

| Endothrix | Arthrospores located within hair shaft; examples are Trichophyton spp. |

| Fungus | Filamentous or unicellular, achlorophyllic organism with true nucleus enclosed in membrane and containing chitin in cell wall |

| Fusiform | Spindle shaped; examples are macroconidia of Fusarium spp. |

| Geophilic | Fungi that reside in soil; examples are Microsporum gypseum and Coccidioides immitis |

| Germ tube | Tubelike outgrowth produced by germinating cells; develops into hypha; example is Candida albicans |

| Hyaline | Transparent, clear, or colorless, usually in reference to hyphae; examples are Fusarium and Penicillium spp. |

| Hypha | Individual, threadlike filament comprising vegetative fungal growth |

| Macroconidium | Larger of two sizes of conidia, usually multicellular; examples are Microsporum gypseum and Microsporum nanum |

| Microconidium | Smaller of two sizes of conidia, usually unicellular; examples are Trichosporon verrucosum and Trichosporon mentagrophytes |

| Mold | Multicellular filamentous form of fungus; consists of masses of hyphae that grow together into a mycelium; examples are Aspergillus spp. and zygomycetes |

| Muriform | Conidium with longitudinal and transverse walls; examples are Alternaria alternata and Curvularia spp. |

| Mycelium | Mass of branching filaments (hyphae) that makes up vegetative growth of fungus |

| Mycetoma | Fungal tumor of cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues with triad of clinical signs (swelling, draining sinuses, grains, or granules in exudates) |

| Mycosis | Disease caused by a fungus |

| Phaeohyphomycosis | Fungal infections whose tissue form is dark-walled hyphae; usually associated with dematiaceous fungi |

| Phialide | Flasklike structure that produces conidia; examples are Aspergillus and Phialophora spp. |

| Propagule | Unit that is able to give rise to another organism |

| Pseudohypha | Chain of yeast cells; result of budding and elongation without detachment, forming hyphalike filament; examples are Candida albicans and Trichosporon spp. |

| Rhizoid | Short, branching hypha that resembles a root; examples are Rhizopus spp. |

| Ringworm | Superficial skin infection caused by dermatophytes; derived from ringlike lesions once thought to be caused by wormlike organisms |

| Sclerotic bodies | Large, round, brownish, thick-walled cells with vertical and horizontal septa; found in tissue sections from animals affected with chromoblastomycosis |

| Septate | Having cross-walls; examples are Aspergillus spp. |

| Sessile | Direct hyphal attachment; no stalk involved. |

| Sexual state | Part of life cycle during which organism reproduces by fusion of two nuclei; in mycology, also known as the “perfect state” |

| Spherule | Large round structure containing spores; examples are Coccidioides immitis and Rhinosporidium seeberi |

| Sporangiophore | Spore-bearing structure, usually closed, on which sporangium develops; examples are Rhizopus and Mucor spp. |

| Sporangiospore | Asexual spore produced within a sporangiophore |

| Sporangium | Closed, often spherical, structure that contains sporangiospores; examples are zygomycetes |

| Spore | Propagule that develops asexually within a sporangium or by sexual reproduction (ascospore, basidiospore, or zygospore) |

| Sterigmata | Specialized hypha that bears a conidium; examples are Aspergillus spp. |

| Teleomorph | Sexual form of conidial fungus |

| Thallus | Vegetative body of a fungus |

| Tuberculate | Knoblike projections from a cell; examples are macroconidia of Histoplasma capsulatum |

| Vesicle | Swollen or bladderlike cell produced at terminal end of condiophore; examples are Aspergillus spp. |

| Yeasts | Unicellular, budding fungi; examples are Malassezia pachydermatis and Candida albicans |

| Zoophilic | Fungi associated with animals |

| Zoospore | Motile asexual spore |

| Zygospore | Thick-walled sexual spore produced by zygomycetes |

PRACTICAL PROCEDURES FOR DIAGNOSIS OF FUNGAL DISEASES

Obtaining the proper specimen for diagnosis is of paramount importance. General guidelines are much the same as those for bacterial specimen collection and include aseptic collection techniques, collection from sites representative of the disease process, collection before antifungal therapy, and collection of an adequate volume of material. Procedures are detailed in Table 44-3.

TABLE 44-3 Collection of Clinical Specimens for Diagnosis of Fungal Disease

| Specimen | Container | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Hairs | Paper envelope (dry conditions inhibit overgrowth of bacterial or saprophytic fungal contaminants) | Wash and dry affected area with soap and water. With forceps, epilate hairs from the periphery of an active lesion. Pull hairs in the direction of growth to include the root. Look for broken, stubby hairs, which are often infected. Useful for diagnosis of dermatophytosis. |

| Skin | Paper envelope | Clean skin with alcohol gauze sponge (cotton leaves too many fibers). Scrape the periphery of an active lesion with a sterile scalpel blade. Also, obtain crusts and scabs. Useful for diagnosis of dermatophytosis. |

| Nails | Paper envelope | Proven nail infections in animals are rare. Cleanse affected nail with alcohol gauze. Scrape with a scalpel blade so that fine pieces are collected. Also, collect debris under the nail. Useful for diagnosis of onchyomycosis. |

| Biopsy | Sterile tube in sterile saline or water | Normal and affected tissue should be included. Important to prevent specimen desiccation. |

| Urine | Sterile tube | Centrifuge and use sediment for direct examination and culture. Useful for diagnosis of histoplasmosis. |

| Cerebrospinal fluid | Sterile tube | Useful for diagnosis of cryptococcosis. Make india ink preparation to observe encapsulated yeasts. |

| Pleural/abdominal fluid | Sterile tube | If fluid contains flakes or granules, they should be included because these are actual colonies of organisms. |

| Transtracheal/bronchial washings | Sterile tube | Centrifuge and use sediment for direct examination and culture. Useful for diagnosis of systemic mycoses. |

| Nasal flush | Sterile tube | Centrifuge and use sediment for direct examination and culture. Useful for diagnosis of nasal aspergillosis and guttural pouch mycosis. |

| Ocular fluid | Sterile tube or syringe | Examine directly. Inoculate onto plated fungal media immediately after collection. Useful for diagnosis of ocular blastomycosis. |

Microscopic examination of clinical materials and isolates obtained by fungal culture is used extensively in fungal identification. Most specimens suspected to contain fungi are initially examined in wet mounts to prevent morphologic distortion of fungal morphology. Wet mounts in KOH are incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature; KOH acts as a clearing agent, digesting the proteinaceous components of host cells and leaving the polysaccharide-containing fungal cell wall intact and more apparent. After digestion, mounts are examined at 100× and 400× magnification for fungal elements. The microscopic appearance of fungi and fungal-like agents in direct examination of clinical material is given in Table 44-4.

TABLE 44-4 Microscopic Appearance of Fungi and Fungal-Like Agents in Clinical Specimens

| Disease | Microscopic Examination Method | Appearance |

|---|---|---|

| Aspergillosis | Wet mount (lactophenol cotton blue or KOH) | Septate hyphae with dichotomous branching; may see fruiting heads |

| Blastomycosis | Wet mount | Thick, double-walled budding yeasts with broad bases of attachment to mother cells |

| Candidiasis and other yeast infections | Wet mount | Budding and nonbudding yeasts; pseudohyphae may be present |

| Coccidioidomycosis | Wet mount | Spherules with and without endospores |

| Cryptococcosis | India ink | Encapsulated yeasts |

| Dermatophytosis | Wet mount | Hairs with arthrospores (endothrix or ectothrix), hyphae or sheath of spores around skin and nails |

| Histoplasmosis | Hematologic stain | Small yeasts with narrow necks of attachment to mother cells, often within macrophages |

| Mycetoma | Wet mount | Dark brown chlamydospores and hyaline hyphae in crushed granules |

| Phaeohyphomycosis | Wet mount | Dark hyphae |

| Pneumocystosis | Hematologic stain | Cysts and trophozoites |

| Protothecosis | Wet mount | Spherical to oval nonbudding, small and large cells containing two or more autospores |

| Rhinosporidiosis | Wet mount | Spherules (some large) with and without endospores |

| Sporotrichosis | Hematologic stain | Small oval to round to cigar-shaped yeasts |

| Zygomycosis | Wet mount | Broad, relatively nonseptate hyphae |

KOH, Potassium hydroxide.

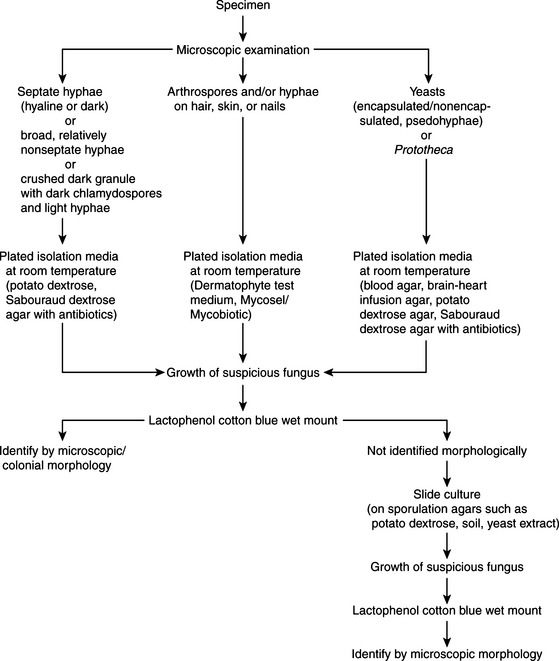

Fungal specimens should be inoculated onto media that ensure adequate fungal growth and preclude the growth of bacterial contaminants. Traditional media for primary isolation include Sabouraud dextrose and potato dextrose agars. These have a high sugar content and acidic pH that inhibit most bacteria but are supportive for fungi. Media may be made more selective by addition of antibiotics such as chloramphenicol, gentamicin, penicillin, or streptomycin to further inhibit bacterial growth. Cycloheximide, an antifungal agent, may be added to potato dextrose or Sabouraud dextrose agar to prevent overgrowth of saprophytic fungi. Mycosel (or Mycobiotic) are two commercial formulations containing cycloheximide. Because this agent can be inhibitory to some pathogenic fungi (e.g., most zygomycetes, Cryptococcus neoformans, and Aspergillus fumigatus), it is advisable to use media with and without cycloheximide for fungal specimen processing. Plates are routinely incubated at 25° to 30° C for up to 6 weeks. If dimorphic fungi are suspected, enriched media such as brain-heart infusion agar with 5% blood are incorporated. Blood enrichment and 37° C incubation temperatures promote the growth of the yeast phase. For isolation of the ringworm fungi, a partially differential and selective medium is used. Dermatophyte test medium contains antibiotics, cycloheximide, and an indicator to demonstrate a rise in pH, consistent with the growth of dermatophytes. Processing schemes for clinical materials appear in Figures 44-4 and 44-5.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree