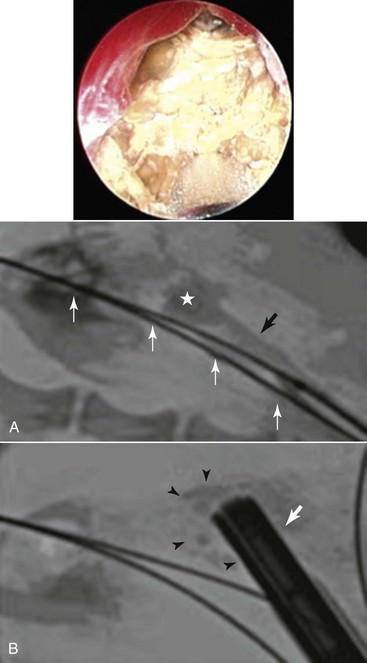

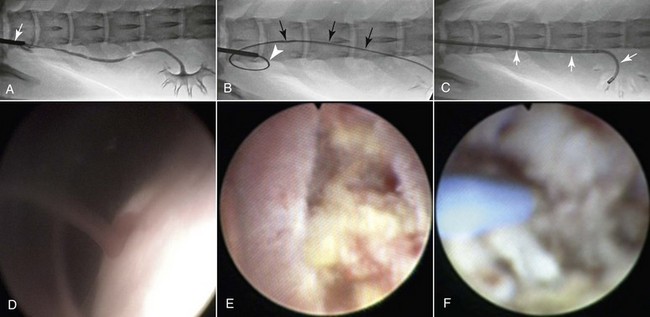

Chapter 195 Various flexible and rigid endoscopes are used for IE procedures. Rigid cystoscopy is commonly performed in female animals for urethral, bladder, and ureteral access. Recommended endoscope diameters (at the tip) range from 1.9 to 4 mm, depending on the size of the patient. Flexible ureteroscopes are used for urethral and bladder access in male dogs (2.5 to 2.8 mm) and for ureteral access in animals large enough to accept such diameters (>15 kg). Rigid nephroscopes are needed (5.3 to 7.3 mm) for percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) procedures. Different types of intracorporeal lithotriptors and lasers are available for various IE procedures such as ultrasonic, electrohydraulic, pneumatic, shock wave, and holmium: yttrium-aluminum-garnet (holmium:YAG) lithotriptors, and the diode-type laser (see Web Chapter 70). In addition, an arsenal of catheters, wires, stents (both metallic [urethral] and polyurethane [ureteral]), and baskets are useful for the varied patient population in veterinary practice. A subcutaneous ureteral bypass (SUB) device is now more commonly used for the treatment of feline ureteral obstructions. This is a nephrostomy catheter and a cystostomy catheter that are attached subcutaneously to a shunting port that allows urine to drain directly from the kidney to the bladder, without the need to salvage the ureter. The direct treatment of nephroliths is necessary only when they become problematic, which is the case less than 10% of the time in the authors’ experience. Nephroliths are considered problematic when one of the following occurs: recurrent urinary tract infections (despite administration of appropriate antibiotic therapy for >8 to 12 weeks), pyelectasia or hydronephrosis, worsening renal function, pain and discomfort, or resulting intermittent ureteral obstruction. Traditional open surgical options to treat problematic nephroliths (e.g., nephrotomy, nephrectomy) are associated with frequent complications and high long-term morbidity. In a clinical study of dogs, approximately 43% had stone fragments remaining after surgery and 23% had procedure-related complications (Gookin et al, 1996). Additionally, 67% of dogs had evidence of renal azotemia that developed following nephrectomy. In a feline study of normal cats there was a 10% to 20% decrease in the glomerular filtration rate of the kidney in which a nephrotomy was performed (King et al, 2006). It is important to realize that in healthy animals the renal hypertrophic mechanisms are still functional, but in clinically affected dogs and cats this process already has been exhausted, which makes the change in renal function more dramatic. The use of less invasive approaches, such as extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) (for stones of <1.5 to 2 cm) or PCNL (for stones of >1.5 to 2 cm), has been shown to be associated with preservation of renal function in humans. PCNL is highly effective in removing all stone fragments in the calices and does not require cutting of the nephrons. Instead, tissues are spread apart with the use of a balloon dilation kit to allow an endoscope and intracorporeal lithotriptor to remove the stone debris effectively. In humans, PCNL is considered the standard of care for nephroliths or proximal ureteroliths too large to be treated with ESWL or laser lithotripsy (>1.5 to 2 cm). PCNL also has been performed successfully in clinical veterinary patients. This procedure has been shown to have minimal or no negative effect on renal function in both children and adults with large stone burdens, solitary kidneys, or renal insufficiency. This minimally invasive endoscopic procedure allows access to the renal pelvis through a small sheath that is placed under fluoroscopic guidance (Figure 195-1). Once a tract is made into the renal pelvis, a nephroscope and intracorporeal lithotrite are used for stone fragmentation and removal. The aim is to minimize morbidity and preserve as much renal function as possible while removing all stone fragments to prevent the development of a ureteral obstruction and progressive renal insufficiency. The success rate of PCNL has been documented at 90% to 100% in both the adult and the pediatric human populations, and the authors have experienced the same in veterinary patients. Figure 195-1 Dog with nephroliths undergoing percutaneous nephrolithotomy. The endoscopic image on the top shows the calcium oxalate nephrolith inside the renal pelvis during ultrasonic and electrohydraulic intracorporeal lithotripsy. A, Percutaneous access is obtained using ultrasonography and fluoroscopy. An 18-gauge catheter punctures the kidney onto the nephrolith (asterisk). A guidewire (white arrows) is advanced down the ureter into the bladder and out the urethra for through-and-through access. A second wire is advanced down the ureter for placement of the renal access sheath (black arrow). B, Nephroscope (white arrow) through the ureteral access sheath and multiple stone fragments are visualized (black arrowheads). It is possible to perform ureteroscopy in dogs larger than approximately 15 kg for visualization of renal hemorrhage. This procedure is challenging to perform in dogs because the canine ureter typically is less than 2 mm in diameter and the smallest ureteroscope currently available is approximately 2.5 mm in diameter. Ureteral access is obtained via cystoscopy; a guidewire is advanced up the ureter into the renal pelvis and the endoscope is advanced over the guidewire under fluoroscopic and endoscopic guidance (Figure 195-2). The ureteral and renal pelvic mucosa are examined; if a bleeding lesion is identified, electrocautery can be applied endoscopically to stop the bleed. Figure 195-2 Female dog with idiopathic renal hematuria. Dorsoventral abdominal fluoroscopic image during ureteroscopy (caudal is left and cranial is right) and ureteroscopic images during cauterization. A, A cystoscope (white arrow) is used to identify the ureterovesicular junction, and a ureteral catheter is advanced up the most distal aspect of the ureter for retrograde ureteropyelography using a contrast agent (Iohexol). B, An angled-tipped hydrophilic 0.035-inch guidewire (black arrows) is advanced through the working channel into the ureteral opening, up the ureter, and into the renal pelvis. The J-hooked distal ureter is observed (white arrowhead). C, The cystoscope is removed over the guidewire, and the flexible ureteroscope is advanced over the wire and into the renal pelvis (white arrows). D, During cystoscopy the left ureterovesicular junction is seen to have jets of bloody urine identifying the side of bleeding. E, A lesion on the renal papilla inside the renal pelvis that is bleeding. F, An electrocautery probe (blue) is used through the flexible ureteroscope for cauterization.

Interventional Strategies for Urinary Disease

Equipment

Kidney and Ureter

Interventional Approach to Nephrolithiasis

Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy

Interventional Approach to Essential Renal Hematuria

Ureteroscopy

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Interventional Strategies for Urinary Disease

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue