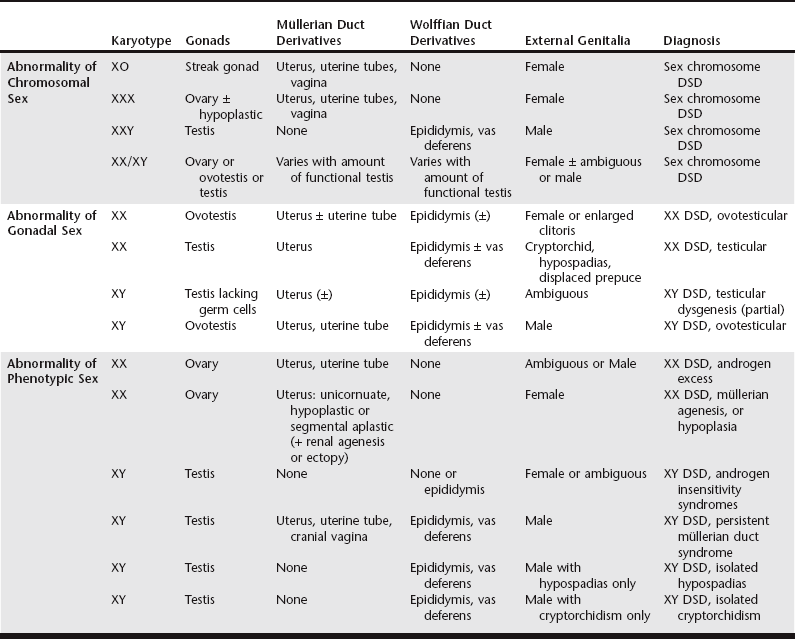

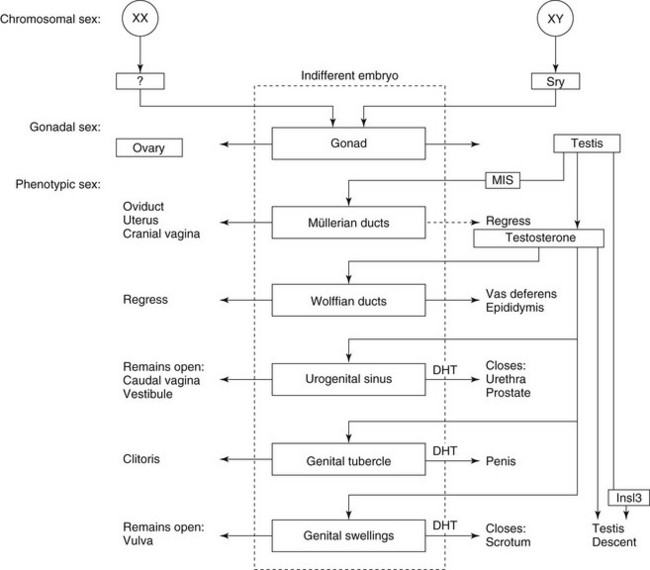

Chapter 217 Normal sexual development depends on successful completion of three consecutive steps: (1) establishment of chromosomal sex, (2) development of gonadal sex, and (3) development of phenotypic sex. Chromosomal sex, which corresponds to genetic sex in normal animals, is established at fertilization. The zygote receives either two X chromosomes or an X and a Y chromosome and maintains this chromosomal constitution in all cells by mitotic division. Morphology of early XX and XY embryos is sexually indifferent. Both have a genital ridge, from which the testis or ovary develops. They also have müllerian and wolffian ducts, a urogenital sinus, a genital tubercle, and genital swellings, from which the internal and external genitalia will arise (Figure 217-1). Differentiation of the genital ridge into a testis or an ovary defines gonadal sex and marks the end of the sexually indifferent stage. Although several genes are necessary for normal development through the sexually indifferent stage, genes that determine gonadal sex have a pivotal role in sexual development. Figure 217-1 Major steps in normal sexual development. (Modified with permission from: Meyers-Wallen VN, Patterson DF: Disorders of sexual development in the dog. In Morrow DA, editor: Current therapy in theriogenology, ed 2, Philadelphia, 1986, WB Saunders, p 567.) Gonadal sex typically is determined by sex chromosome constitution: presence of the Y chromosome results in testis development, whereas its absence results in ovarian development. The sex-determining region Y gene, SRY, is located normally on the Y chromosome, and the SRY protein is the signal for initiating testis differentiation in the genital ridge (Jakob and Lovell-Badge, 2011). In the absence of the Y chromosome and SRY, the genital ridge normally becomes an ovary. However, ovarian induction is not a passive process: testis-promoting and ovary-promoting signaling pathways are responsible for gonadal sex determination (Quinn and Koopman, 2012). Phenotypic sex is controlled normally by gonadal sex. If the genital ridges are removed from XX or XY embryos before gonadal differentiation occurs, a female phenotype develops, indicating that the embryo is programmed to develop as a female and must be diverted from this pathway to develop as a male. The critical diverting step is testis development. The testis secretes two substances that act within embryonic critical periods to induce masculinization: (1) müllerian-inhibiting substance/antimüllerian hormone (MIS/AMH), which causes the müllerian ducts to regress, and (2) testosterone, which stimulates formation of the vasa deferentia and epididymides from the wolffian ducts (see Figure 217-1). In the external genitalia, testosterone is converted to dihydrotestosterone (DHT) by the enzyme 5α-reductase. Dihydrotestosterone stimulates formation of the prostate and male urethra, penis, and scrotum from the urogenital sinus, genital tubercle, and genital swellings, respectively (see Figure 217-1). Descent of the testes into the scrotum completes the male external genitalia, but the genetic and hormonal control of this process is incompletely understood. Testosterone and insulin-like 3 factor (INSL3), both secreted by Leydig cells, are required for testis descent, as are their receptors, but other unknown factors also likely are involved. In the absence of testicular secretions, female genitalia develop (see Figure 217-1). For the purpose of pursuing a diagnosis, it is useful to identify the initial step at which development differs from normal, either at the level of chromosomal sex, gonadal sex, or phenotypic sex (Table 217-1). A more precise diagnosis defines the disorder according to its etiology, preferably by the specific gene mutation responsible for the defect. To eliminate older, confusing terms such as pseudohermaphrodite and facilitate incorporation of molecular diagnoses, a new nomenclature has been established (Pasterski, Prentice, and Hughes, 2010). With this terminology, intersex individuals are described as having a disorder of sexual development (DSD), a nonspecific term. All DSDs are categorized initially by karyotype, with sex chromosome DSD including all errors at the level of chromosomal sex. Errors occurring at the level of gonadal sex or phenotypic sex now are divided according to karyotype, either XX DSD or XY DSD (see Table 217-1). Many disorders of sexual differentiation have been reported, in which the primary cause was an abnormality in the number or structure of the sex chromosomes. To summarize, animals with abnormalities in sex chromosome number, such as those with XXY and XO syndromes and their variants, generally have underdeveloped genitalia and are sterile but are unambiguously male or female in phenotype (see Table 217-1). However, some XXX dogs have exhibited estrous cycles, and pregnancy was reported in an XXX variant cat. The gonadal sex of chimeras and mosaics depends on the distribution of XX and XY cells within the genital ridge. Phenotypic sex then is determined by the presence and amount of functional testicular tissue in the gonad. Sex chromosome DSDs usually are caused by errors in chromosome segregation or by fusion of zygotes. Therefore familial aggregation of affected individuals is not expected. All animals with XX disorders of sexual development (XX DSDs) have a female karyotype and are separated according to whether the primary defect occurs at or below the level of the gonad (see Table 217-1). For those individuals with the primary defect occurring at the level of the gonad, these animals develop testicular tissue (ovotestis or testis) despite having a normal female karyotype. This has been reported in dogs but not in cats. Such animals previously were termed sex-reversed because the chromosomal sex and the gonadal sex of the individual disagree. Affected dogs have at least one ovotestis (ovotesticular XX DSD) or bilateral testes (testicular XX DSD) and previously were called XX true hermaphrodites or XX males, respectively. Both phenotypes can appear in the same family. Phenotypic masculinization depends on the amount of testicular tissue in the affected individual. Thus those with ovotestes may have normal female external genitalia, an enlarged clitoris with an os clitoris that resembles a penis, or any phenotype in between. Those with bilateral testes generally have a caudally displaced prepuce and a penis with hypospadias and are bilaterally cryptorchid. This DSD has been reported as a familial trait in at least 28 canine breeds and two mixed breeds (Box 217-1). In the American cocker spaniel, this DSD is inherited as an autosomal-recessive trait, but the mode of inheritance has not been determined in all breeds. The Y-linked SRY gene is absent in all affected dogs reported, ruling out translocation as the cause. Diagnosis depends on confirmation of a 78,XX karyotype and histology demonstrating at least one ovotestis or testis. To define the etiology more precisely and aid in genetic counseling, the diagnostic workup should include a molecular test for SRY. Whereas elevation in peripheral testosterone concentrations in response to GnRH or hCG stimulation strongly suggests that testicular tissue is present, it is not diagnostic. The inability to provoke testosterone elevation by a stimulation test does rule out the diagnosis. In addition to dogs, ovotesticular or testicular XX DSD in which the individuals are SRY negative has been reported in several mammals. Mutations that cause SOX9 or SOX3 overexpression or reduce RSPO1 expression have been identified in affected humans and mice (Jakob and Lovell-Badge, 2011). This form of canine XX DSD has been studied most extensively in a pedigree derived from the American cocker spaniel, in which an autosomal-recessive mode of inheritance was identified through experimental matings (Meyers-Wallen, 2012). A genome-wide linkage analysis in this model pedigree identified linkage to CFA29. A candidate gene has not been identified, and SOX9, RSPO1, and SOX3 are not located in this region. The causative mutation is likely to be the same in American and English cocker spaniels because they share recent common ancestry. It is unclear whether the same gene locus is responsible in other breeds.

Inherited Disorders of the Reproductive Tract in Dogs and Cats

Normal Sexual Development

Diagnosis of Disorders of Sexual Development

Sex Chromosome Disorders of Sexual Development

XX Disorders of Sexual Development

Disorders of Gonadal Development

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Inherited Disorders of the Reproductive Tract in Dogs and Cats

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue