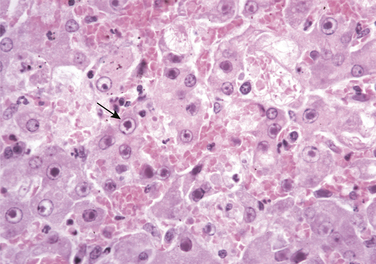

Chapter 18 Infectious canine hepatitis (ICH) is an uncommonly recognized disease of dogs that is caused by canine adenovirus type 1 (CAV-1), a non-enveloped, icosahedral double-stranded DNA virus that is antigenically related to CAV-2 (see Chapter 17) (Figure 18-1). CAV-1 also causes disease in wolves, coyotes, skunks, and bears, as well as encephalitis in foxes, but the diversity of wildlife hosts is not as great as that for CDV. Ferrets are not susceptible.3 ICH has also been referred to as Rubarth’s disease, after Carl Sven Rubarth, a veterinarian who first described the disease in the late 1940s.1 Over the subsequent 10 years, ICH was described worldwide, including the United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Australia, Japan, Brazil, and throughout Europe. The virus can survive for months at room temperature, but should be readily inactivated by disinfectants with activity against canine parvovirus (CPV).4 Disease most commonly occurs in dogs that are less than 1 year of age, but was reported in adult dogs before widespread vaccination for ICH was introduced. FIGURE 18-1 Structure of canine adenovirus. The virus is a non-enveloped, lcosahedral virus with fibers (purple) that radiate outwards from the virion. The strong antigenic relationship between CAV-1 and CAV-2 is clinically important, because vaccines that contain CAV-2 protect against infection with CAV-1 and vice versa. After the introduction of CAV-1 vaccines, ICH largely disappeared, but over the past decade it has reemerged, with published reports of disease from Italy, Switzerland, and the United States.5–8 Disease in Europe has been associated with puppy trading from kennels in eastern European countries and possibly spillover of virus circulating in wildlife.9 In Italy, three outbreaks occurred in shelters in southern Italy, and the others involved purebred puppies imported from Hungary a few days before the onset of clinical signs. Several of the dogs were co-infected with other viruses, such as canine distemper virus (CDV), CPV, or canine enteric coronavirus. Encephalopathy due to CAV-1 infection was described in nine 5-week-old Labrador retriever puppies from Arkansas in the United States, all of which belonged to the same litter.8 The litter was from an unvaccinated bitch. These case descriptions confirm that CAV-1 continues to circulate in the dog population and can result in severe disease in young dogs when vaccination does not occur, is improperly timed, and stress, co-infections, and overcrowded conditions prevail. CAV-1 is shed in saliva, feces, and urine, and transmission occurs through direct dog-to-dog contact or contact with contaminated fomites such as hands, utensils, and clothing. Ectoparasites such as fleas and ticks are also potential mechanical vectors.4 Airborne transmission does not appear to be important. Initial infection occurs through the nasopharyngeal, conjunctival, or oropharyngeal route, and the virus replicates within the tonsils, after which it spreads to regional lymph nodes and the bloodstream via lymphatics. Subsequently, infection of hepatocytes and endothelial cells within a variety of tissues occurs, such as the lungs, liver, kidneys, spleen, and eye with resultant hemorrhage, necrosis, and inflammation. The virus replicates in the nucleus of host cells, where crystalline arrays of virions form. There is severe condensation and margination of nuclear chromatin, with inclusion body formation (Figure 18-2). The virions are released by cell lysis, which leads to tissue injury and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Within the liver, the virus initially infects Kupffer’s cells and subsequently spreads to hepatocytes. FIGURE 18-2 Infection of hepatocytes and endothelial cells with CAV-1 produces characteristic basophilic intranuclear inclusions surrounded by a clear zone that separates them from the marginated chromatin (arrow). H&E stain. (Courtesy Dr. W. Crowell, College of Veterinary Medicine, The University of Georgia and Noah’s Archive, College of Veterinary Medicine, The University of Georgia. In Zachary JF, McGavin M. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease, 5 ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2012.) Clinical signs generally occur after an incubation period of 4 to 9 days, although many dogs probably show no signs of illness.4 Three overlapping disease syndromes have been described. The first is peracute disease with circulatory collapse, coma, and death after a brief illness that lasts less than 24 to 48 hours. The second, most commonly described syndrome is acute disease, which is associated with high morbidity and reported mortality rates of around 10% to 30%.4 Dogs with acute disease either recover or die within a 2-week period. The third is a more chronic form that occurs in dogs with partial immunity, with death due to hepatic failure weeks (subacute disease) or months (chronic infection) after initial infection.10 Acute disease is variably characterized by the presence of fever, tonsillitis, conjunctivitis, inappetence, lethargy, weakness, polydipsia, vomiting, hematemesis, diarrhea, cough, tachypnea, and icterus. Diarrhea may contain frank blood or melena. Widespread petechial and ecchymotic hemorrhages and hematuria can be seen. Corneal edema (“blue eye”) occurs in the first week of illness and results from replication of virus within corneal endothelial cells (Figure 18-3). Rarely, neurologic signs such as seizures, ataxia, circling, apparent blindness, head pressing, and nystagmus have been reported in association with CAV-1 encephalitis.7,8 The development of neurologic signs may also represent hepatic encephalopathy, intracranial thrombosis or hemorrhage, or, as occurred in one outbreak, concurrent infection with CDV.7 FIGURE 18-3 Young adult dog with corneal edema from an Italian shelter outbreak of CAV-1 infection. (Courtesy Dr. Nicola Decaro, Department of Veterinary Public Health, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine of Bari, Italy.) The antibody response appears 7 days after infection and limits tissue damage. Viral persistence within the renal glomeruli, uveal structures of the eye (the iris and ciliary body), and the cornea can trigger immune complex formation in dogs that recover from acute illness. This leads to glomerulonephritis with proteinuria, severe uveitis, and persistent corneal edema in some surviving dogs. Glomerulonephritis usually occurs about 1 to 2 weeks after the acute signs resolve. Glomerular lesions contain deposits of viral antigen, IgG, IgM, and C3.11,12 Infection of the glomerular endothelium is followed by a persistent tubular infection, development of interstitial nephritis, and viruria, but chronic renal failure has not been described. Viral shedding in the urine can occur for up to 6 to 9 months after infection. Anterior uveitis is associated with massive influx of inflammatory cells into the anterior chamber. Occasionally persistent corneal edema fails to resolve for months and may be associated with complications such as glaucoma.13 The Afghan hound is reportedly susceptible to this complication.14 In experimental infections with CAV-1, chronic hepatitis with extensive fibrosis was observed in some dogs that recovered from acute illness, with survival for up to 8 months.10 The virus could not be found in hepatic lesions from these dogs. Attempts to detect CAV-1 in the liver of other dogs with chronic active hepatitis using PCR assays have to date been unrewarding.15–17

Infectious Canine Hepatitis

Etiology and Epidemiology

Clinical Features

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree