11 Immune-mediated/allergic diseases

Urticaria and angio-oedema (‘hives’)

Pemphigus vulgaris (EPV) and bullous pemphigoid (BP)

Equine cutaneous (discoid) lupus erythematosus

Immune-mediated (cutaneous) vasculitis

Pastern (and cannon) leukocytoclastic vasculitis

Purpura haemorrhagica (immune-mediated vasculitis)

Equine nodular eosinophilic vasculitis and arteritis

Systemic/cutaneous lupus erythematosus- like syndrome (SLE-like syndrome)

Sarcoidosis (generalized granulomatous disease)

Multisystemic eosinophilic epitheliotropic disease/generalized eosinophilic disorder (hyper-eosininophilic syndrome)

Equine insect bite hypersensitivity/allergy (summer itch/insect dermatitis, sweet itch, Queensland itch)

Drug eruption (cutaneous adverse drug reaction)

Sterile, nodular panniculitis/steatitis

Eosinophilic dermatitis with collagen necrosis/eosinophilic granuloma/collagenolytic granuloma

Inflammatory changes occur in the skin whenever it is injured. These changes are initially related to the specific cause and, secondarily, may relate to autologous changes which develop later. Regardless of the cause, be it heat, cold, infection due to bacterial, fungal, viral or parasitic organisms, radiation, trauma, or allergens, the skin response will be characterized by responses that involve blood vessels, tissue fluids and cells. These changes will be identifiable clinically as the cardinal signs of inflammation, namely heat, pain, redness, swelling and variable loss of function.

The various ways in which the body can respond have been broadly grouped into four types of hypersensitivity (Gell & Coombs 1964) and these have been described in Chapter 1, p. 14). While they are fairly well defined, many reactions are complexes of these and so may show broad variations in clinical features. Types 1, 2 and 3 all rely on antigen–antibody reactions and therefore induce clinical effects following introduction of the antigen to a previously sensitized animal (in the case of type 1 hypersensitivity usually in less than 4 hours and possibly within minutes). Type 4, however, is cell-mediated and has no immediate antibody–antigen component. Therefore, the responses are delayed for a variable period of time (24–72 hours). The clinical situation, however, is frequently complicated by secondary effects such as self-inflicted trauma and the clinician is only able to examine a single moment in the continuing/continuous process. Although crusting and scaling (dry dermatoses) are prominent features of many allergic or autoimmune conditions, other signs, including nodules and moist dermatosis, may be present.

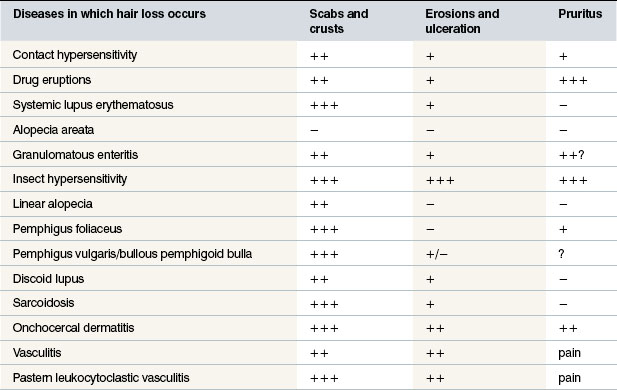

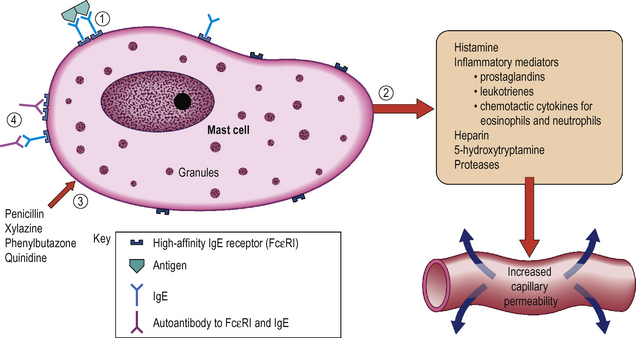

Knowledge of immune-mediated diseases is being expanded and the similarity to corresponding human disease is evident. However, the horse may present significant or minor variations to the general pattern seen in other species. Similar names are therefore given to some diseases, but it is important to realize that species differences may not entirely justify the name. Extrapolation from the name of the disease to possible diagnostic features and treatment may also therefore not be justified. Further knowledge and research into these diseases may well reclassify them. Table 11.1 demonstrates the major clinical features of the allergic and autoimmune diseases of the horse, dividing these broadly into those associated with hair loss or no hair loss.

Table 11.1A General clinical signs of allergic and autoimmune disorders of the horse in which hair loss does occur

Table 11.1B General clinical signs of allergic/immunological disorders in which hair loss does not (initially) occur

Urticaria and angio-oedema (‘hives’)

Profile

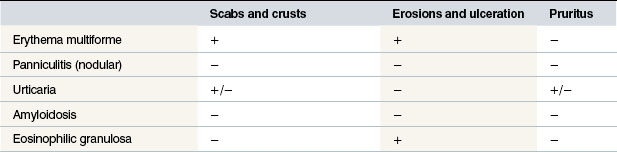

The aetiopathogenesis of urticaria in horses is complex; a wide variety of factors have been identified as potential causes (Tables 11.2 and 11.3); this can possibly be explained by the fact that the horse seems to be more liable to the condition than many other species and that the clinical signs of ‘urticaria’ are best viewed as a final manifestation common to many related and apparently unrelated conditions (Stannard 1994a).

Table 11.2 The potential causes of urticarial lesions and urticaria-like skin signs

| Drugs |

| Physical urticaria |

| Infections |

| Stress-related urticaria |

| Ingestion of vasoactive chemicals |

| Chronic idiopathic urticaria |

After Fadok V A (1990) Of horses and men: urticaria. Veterinary Dermatology 1:103–111.

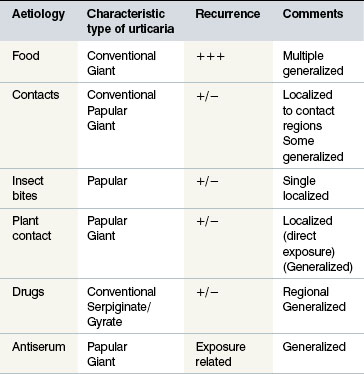

The aetiopathogenesis is not clear and although the condition does resemble that in other species there are significant differences in the horse. However, the basic aspects are likely to be similar. Degranulation of mast cells (and to a lesser extent perhaps, basophils) is presumed to be the basic pathogenesis involving the liberation of chemical mediators which cause increased vascular permeability, inflammation and protein leakage with consequent wheal formation (Fig. 11.1).

• Immunological (type 1 and type 2 hypersensitivity responses) and non-immunological (heat, cold, pressure, exercise, some drugs) causes have been identified but in some cases no aetiology is established – usually termed idiopathic urticaria. The latter does not mean that there is no cause, it simply indicates that we have no real understanding of the possible cause(s).

• Immunological or hypersensitivity reactions in which injected (drugs), ingested (chemical, feeds) or inhaled (pollen, dust, chemicals, moulds) antigens/allergens are delivered to the skin systemically rather than by local contact. Penicillin is the most commonly implicated drug responsible for urticaria.

• Allergic urticaria arises from drugs, food, inhaled allergens (pollens, moulds) (Evans 1987) or more rarely by direct skin or mucous membrane contact. These should be carefully distinguished from allergic contact dermatitis.

• Physical urticaria arises without any immunological component. Dermatographism arises when a wheal develops from a blunt ‘scratch’ on skin (Fig. 11.2). ‘Cold’ or temperature-related urticaria can arise from either cold, heat or even light under some conditions. Exercise-induced urticaria may also be encountered following heavy exercise (particularly in hot or very cold conditions).

‘Pitting-on-pressure’ test: When steady and firm digital pressure is applied to an oedematous swelling or wheal for 10–20 seconds, the imprint/indentation of the finger will remain obvious at the site for several minutes (or longer in some cases) (see Fig. 11.43A, B). Inflammatory or solid/tumour-like swellings do not compress in this way, while fluid-filled swellings are compressible but do not retain the shape of the finger.

Key points: Urticaria and angio-oedema

Key points: Urticaria and angio-oedema

1. Very common complex of conditions that are poorly under-stood in spite of the high incidence. Immunological and non-immunological causes have been identified.

2. Clinical signs include abrupt appearance of wheals of vary-ing sizes and sometimes linear, circular and serpiginous oedematous skin changes. Angio-oedema, in which there is massive intracellular protein loss and plasma exudation, is very rare in horses.

3. Biopsy is remarkably disappointing compared to the clinical lesions. Diagnosis can be suggested by feed/withdrawal trials in which suspected causative feeds are withheld for 2 weeks before being reintroduced to the diet. Radioallergosorbent and ELISA tests and intrademal allergy tests can be used to help identify putative allergens. In many cases a careful history will help considerably. Known exposure to drugs, pos-sible contact allergens and some infections can be helpful.

4. Treatment is usually simple in simple cases – intravenous dexamethasone even at lower doses usually quickly resolves the early cases – even some severe cases respond rapidly. Repeated episodes often become more refractory to treat-ment. Removal of the causative agent is curative.

5. Recurrent episodes become more difficult to treat effectively and may require long-term management and repeated corti-costeroid drugs by injection or by mouth.

Insect bites cause a localized ‘wheal’ but this is a quite different circumstance to true urticaria (see p. 207).

Clinical signs

The onset can be acute or peracute with signs developing within minutes up to a few hours following exposure to the instigating factor. In some cases the onset is far slower and these often are more chronic in nature. Often a careful historical investigation can identify an associated substance such as a feed or a drug.

Characteristically the signs are oedematous lesions of the skin and/or mucous membranes called ‘wheals’ which are flat-topped, papules/nodules with steep-walled sides (Fig. 11.3).

Figure 11.3 Urticaria. Wheals showing the steep-sided, sharply demarcated nature of the typical lesions.

The typical urticarial lesions develop quickly and often fade away equally quickly. Typically the individual lesion is a steep-sided papular dermal swelling – usually there are many and some are confined to specific locations. Single lesions can vary in size from 0.5 cm to 15 cm or more and these can coalesce to produce much larger areas in which individual urticarial plaques are not obvious. Usually, however, under the circumstances the skin takes on a ‘bumpy’ appearance. Anular, arciform and serpiginate urticarial eruptions are common in horses (see p. 258).

Typically the lesions themselves will ‘pit on pressure’, but the surrounding skin will usually be normal and will not pit on pressure. This test may be difficult to apply effectively to small urticarial lesions but they will compress away only to return a few minutes later – testing after clipping gives the best information. Some lesions have slightly depressed centres, but in true urticaria there is no central focus of inflammation (in contrast to insect bites; see p. 207).

Individual urticarial lesions vary in size and shape and, quite arbitrarily, may be divided into:

• Conventional wheals: 2–5 mm in diameter (Fig. 11.4).

• Papular wheals: multiple, small, uniform 3–6 mm diameter wheals (similar to the appearance of insect bites but without a central focus). Insect bites can induce a very similar localized wheal at the site (Fig. 11.5).

• Giant wheals: either single or coalesced, multiple wheals 20–30 cm in diameter or more (Fig. 11.6).

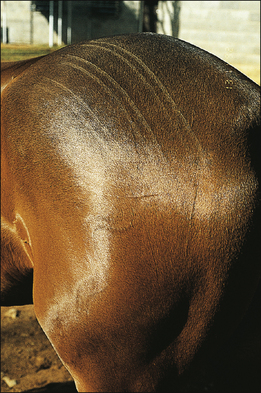

• Linear wheals: usually multiple ‘lines’ of urticarial oedema most often occurring along the sides of the body (Fig. 11.7). This form tends to be more obvious in warmer weather and may be pruritic.

• Anular wheals: ‘doughnut’-like lesions with a regular or irregular ring of oedema surrounding a depressed, non-oedematous or less oedematous centre (Fig. 11.8).

• Gyrate/serpiginate urticaria: the urticarial lesions take on a variety of shapes with some straighter linear, some curvilinear lesions and some serpiginous lesions (Fig. 11.9). This has been referred to as the dermal form of ‘erythema multiforme’ but it should be stressed that this syndrome is not related to ‘true’ erythema multiforme, which is a primary epidermal disease (see Fig. 11.37). Drug reactions appear to be the most common cause of this form of urticaria.

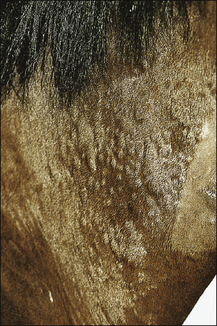

• Exudative urticaria: poorly defined or diffuse exudative oedema of the skin over localized areas or regions (Fig. 11.10). Possibly best regarded as angio-oedema.

Oozing urticaria

Dermal oedema is severe, resulting in oozing of serum from the skin surface and possibly cracking and superficial sloughing of the hair and skin (Fig. 11.10). In the early stages the oedematous lesions will still ‘pit on pressure’ in spite of their apparent severity. Care should be taken to distinguish this from a bullous condition, or an erosive/ulcerative process or a pyoderma or vasculitis.

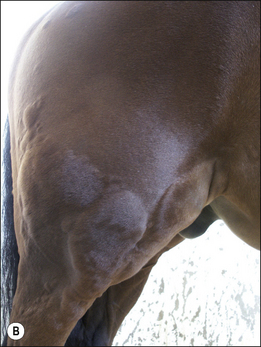

Angio-oedema (angioneurotic oedema)

This is a subcutaneous form of urticaria which tends to be more diffuse owing to lack of restraint of the spread of the fluid through the subcutis (Fig. 11.11). In some cases the condition is more reflective of vasculitis (see p. 27). It usually involves the head and extremities and is more indicative of systemic and/or serious disease than ‘simple’ urticaria. Pruritus may or may not be present. It can easily be mistaken for vasculitis and the skin manifestations of the two conditions may in some cases be indistinguishable. Fortunately in horses angio-oedema is rare.

Differential diagnosis

Papular, conventional and giant urticaria:

• Insect (mosquito/bee/wasp/fly) bites (Stomoxys and Culicoides are the commonest causes): the signs may be limited to the single bite area but a few cases show a more generalized response (often with systemic/generalized organ symptoms such as respiratory obstructions).

• Nettle rash: transient signs arising immediately after skin contact with nettles or other plants.

• Dermatophytosis (Trichophyton equinum, Microsporum spp.): specific epidemiology and microbiological results. Some dermatophyte lesions can be oedematous.

• Dermatophilosis (Dermatophilus congolensis): inflammatory and seldom focal oedema.

• Folliculitis (sterile and bacterial/fungal): variously painful and exudative lesions often associated with marked pain and heat; often marked lymphatic and vascular engorgement).

• Erythema multiforme: benign, long-standing, slowly progressive skin patterning associated with allergic response. This can be classified in some cases with gyrate or serpiginate urticaria but has a more inflammatory nature on biopsy.

• Purpura haemorrhagica: typical history of prior respiratory tract infection. Diffuse cutaneous and subcutaneous oedema, petechiation of mucous membranes and protein leakage.

• Vasculitis (immune-mediated and photoactivated/actinic): various forms associated with inflammatory vascular endothelial damage as a result of direct endothelial damage or immune-mediated damage.

• Haematoma (±haemophilia): fluid-filled, usually non-inflammatory swelling. Usually single or few and often large.

• Lymphangitis: diffuse subcutaneous swelling – sometimes with exudation, associated with diffuse inflammation.

• Abscess/pyoderma: painful swelling with purulent exudate.

• Cellulitis: diffuse, very painful infectious disorder resulting from diffuse interstitial inflammation.

Diagnostic confirmation

• Clinical signs and history are typical. Recurrence or repeated isolated episodes in response to any possible aetiology (see above) is very helpful diagnostically provided that the appropriate information is obtainable. A written daily record of work/activity, feed, management changes and drug administrations is very helpful; many owners are unable to recall enough detail about the previous period when an episode occurs. Most urticarial lesions erupt between 1 and 24 hours after exposure to the causative agent/circumstance.

• There are no ‘typical’ lesion types for specific disease states or specific allergens and many cases have multiple wheals of different types and distributions (Fig. 11.12).

• The distribution of lesions can be helpful. For example, are the lesions restricted to areas where blankets and tack are in contact or are they outside these areas? Some cases show exacerbation when the region is warmed such as under warm lights or with blankets applied to the horse. It is assumed that this reflects a cutaneous response to increased blood supply when greater amounts of the causative agent are delivered faster but this is conjecture rather than fact.

• The response to corticosteroid treatment is helpful. Commonly a single (test) dose results in a dramatic resolution within a few hours at most. However, long-standing cases often respond less rapidly and less completely so the history is very important.

• Biopsy is often unrewarding and can even be misleading. The detection of oedema in a biopsy is complicated by fluid leakage from the biopsy during collection and fixing. In the absence of any cellular responses there may be nothing to report. The section may show non-specific lymphocyte and eosinophil infiltration. However, eosinophils are not an invariable finding in all cases.

• A dermatographism test can be made by scratching the skin with the blunt end of a ballpoint pen and observing for a reaction within 10–15 minutes (a positive reaction is reflected by a marked oedematous wheal which follows the path of the scratch).

• ‘Cold’ urticaria can be induced by applying an ice cube to the skin for a few minutes, and an urticarial wheal developing in<15 minutes is a positive reaction.

• Other allergens can be ‘detected’ by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or radioallergosorbent test (RAST) on a blood (serum) sample. Tests are designed to detect specific IgE proteins which reflect allergic responses. The tests are not widely standardized and in many ways are too sensitive for practical use. They commonly identify groups of proteins, etc., to which the horse is variously ‘allergic’ (see p. 80). Often the test panel is not specific for the horse and so many of the allergens tested have little or no relevance even if they are positive. Furthermore the range of allergens tested is limited – the finding of a positive result does not of course mean that the signs are necessarily associated with it at that time – it could equally be a substance that has not been tested for!

• Intradermal allergy testing can also be used but in the case of urticaria the results are highly variable and this method suffers from the same limitations as the serum IgE/RAST tests (see above).

• Suspected food allergy can only be traced by feeding a ‘hypoallergenic diet’ (such as alfalfa hay only with distilled or boiled water) for 3 weeks and then challenging the horse with each specific single component of the diet for 3 weeks until a positive is identified. Confirmation of this will require a second challenge after withdrawal for 3 weeks. Positive reactions can develop quickly but can also take 2–3 weeks to appear, so it can be a very time-consuming process. Horses undergoing feed exclusion trials often lose weight because it is hard to keep the horse fit on a limited diet. Supplementary oils (especially sunflower or rapeseed oils) can be administered to boost energy requirements. Alfalfa hay is not always available and so a single species (Timothy or rye grass) early cut haylage can be used either alone or with alfalfa to make a more practical forage ration. Many commercial forms of alfalfa have varying supplementary materials such as molasses, minerals, vitamins, oils and often other fibre feeds and so their use is not advised during the trial period.

• ‘Contact’ causes are rare in horses but during diagnostic tests the horse should be kept in a clean stable on paper bedding and all contact with possible sources of insects or other allergens should be avoided. Urticaria arising from known contact with either plants or other materials (tack or chemicals) is easier to investigate and treat – often owners are unaware of the potential significance of short-term exposures.

Treatment

3. Persistence: if the condition persists after 4–6 weeks, it is important to reassess the whole case again and possibly evaluate by intradermal (injection or patch) testing (Chapter 3, p. 81) for atopic disease (IgE) or specific ELISA or RAST tests for IgE. It may be possible in this way to identify possible/probable causes from the panel of positive results and attempt to avoid them. However, the results from these tests are very unreliable and repeated samples from the same horse can give very different results over very short intervals.

Hyposensitization and neutralization may be attempted but this is not generally available and carries risks. It may hold some promise for inhaled allergic urticaria and atopy (see p. 262). The specific dose of the allergen used and the required frequency of challenge are variable according to the individual response but usually the injections have to be maintained throughout life. Recent reports have questioned the relevance and therapeutic benefits of these methods but opinions are divided. Many practitioners feel that they are an effective approach whilst others have less faith in them.

Long-term management

Corticosteroid

The dose of corticosteroid should then be reduced to reach a minimal effective (therapeutic) single daily dose (MESDD). Double this daily dose should then be administered using twice the interval (48 hours for prednisolone and 48–96 hours for dexamethasone) in the mornings only (see p. 96). Provided that this dose is effective it is then gradually reduced to establish a minimum effective alternate-day dose (MEADD). The objective is to use the least possible drug consistent with a complete absence of clinical signs. Concurrently every effort should be made to remove any possible causative agent.

Prognosis/prevention

It is the recurrent and deteriorating cases that create the long-term problem. Some badly affected horses are never free of the condition or the threat of it. Animals that have concurrent signs such as diarrhoea or respiratory tract obstructions are clearly much more difficult to manage.

Atopy

Profile

Little is known about the condition in horses but it is widely recognized as a definitive clinical entity (Scott & Miller 2003a). It is not known whether it is heritable but Arabians and Thoroughbreds in early adulthood appear to be predisposed to the condition (Degler 1997).

Clinical signs

1. Rare, genetically predisposed inflammatory and allergic skin disease that manifests, initially at least, in younger horses

2. The predominate sign is pruritus. Seborrhoea and occasion-ally concurrent respiratory tract and other evidence of allergic disease including urticaria may be present.

3. Diagnosis is based on exclusion of other causes of pruritus, serum ELISA and intradermal or patch skin testing.

4. Treatment is limited in horses to corticosteroids and avoidance strategies of proven or putative trigger factors. Hyposensitiza-tion procedures involving injection of ‘specific’ antigen con-centrations have been reported to be effective in a few cases.

5. The prognosis is guarded – if the allergens can be avoided then the signs will be minimal but will seldom clear completely.

The primary sign is pruritus developing at a young age (Table 11.4). Some cases have urticaria and some are less pruritic than others. There is recurrent pruritus unrelated to season without obvious or histological primary lesions other than self-mutilation. The affected horse may bite aggressively at a localized site until it is significantly damaged and then turn its attention to another site. Horses often bite unrelated regions in subsequent attacks (Fig. 11.13). Some have more general signs but most seem to have body pruritus as opposed to limb or head pruritus but no site is exempt. Rubbing of the skin (even at sites that are not apparently affected at the time of examination) often induces a ‘pleasure response’ at the lips and muzzle.

Table 11.4 Criteria for diagnosis of atopic dermatitis in horses

(a) Pruritus without other defined cause at unpredictable and variable sites (c) Onset within 2 years of birth with progressive deterioration Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|

Key points: Atopy

Key points: Atopy