Chapter 5 Hyperthermia and Fever*

THERMOREGULATION

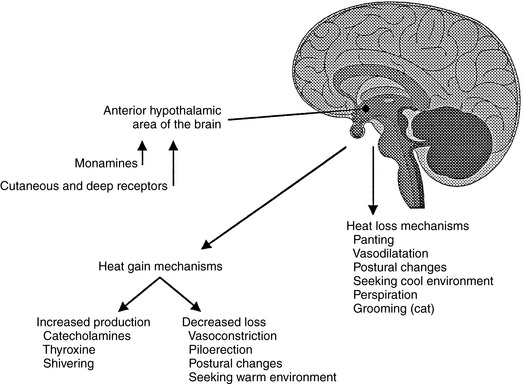

Thermoregulation is the balance between heat loss and heat production. Metabolic, physiologic, and behavioral mecha-nisms are used by homeotherms to regulate heat loss and production. The thermoregulatory control center for the body is located in the central nervous system in the preoptic area of the anterior hypothalamus (AH).1 Changes in ambient and core body temperatures are sensed by the peripheral and central thermoreceptors, and information is conveyed to the AH via the nervous system. The thermoreceptors sense that the body is below or above its normal temperature (set point) and subsequently cause the AH to stimulate the body to increase heat production and reduce heat loss through conservation if the body is too cold, or to dissipate heat if the body is too warm (Figure 5-1). Through these mechanisms, the dog and cat can maintain a narrow core body temperature range in a wide variety of environmental conditions and activity levels. With normal ambient temperatures, most body heat is produced by muscular activity, even while at rest. Cachectic or anesthetized patients or those with severe neurologic impairment may not be able to maintain a normal set point or generate a normal response to changes in core body temperature.

HYPERTHERMIA

Hyperthermia is the term used to describe any elevation in core body temperature above the accepted normal range for that species. When heat is produced or stored in the body at a rate greater than it is lost, hyperthermia results.2,11 The term fever is reserved for those hyperthermic animals in which the set point in the AH has been reset to a higher temperature. In hyperthermic states other than fever, temperature elevation is not a result of the body attempting to raise its temperature but is due to the physiologic, pathologic, or pharmacologic changes that cause heat gain to exceed heat loss. Box 5-1 outlines the various classifications of hyperthermia.

TRUE FEVER

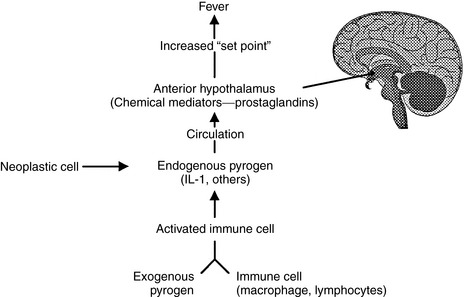

True fever is a normal response of the body to invasion or injury and is part of the “acute phase response.”3 Other parts of the acute phase response include increased neutrophil numbers and phagocytic ability, enhanced T and B lymphocyte activity, increased acute phase protein production by the liver, increased fibroblast activity, and increased sleep. Fever and other parts of the acute phase response are initiated by exogenous pyrogens that lead to the release of endogenous pyrogens (Figure 5-2).4

Figure 5-2 Schematic representation of the pathophysiology of fever.

From Miller JB: Hyperthermia and fever of unknown origin. In Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC, editors: Textbook of veterinary internal medicine, ed 6, St Louis, 2005, Saunders.

Exogenous Pyrogens

True fever may be initiated by a variety of substances including infectious agents or their products, immune complexes, tissue inflammation or necrosis, and several pharmacologic agents. Collectively, these substances are called exogenous pyrogens. Their ability to directly affect the thermoregulatory center is probably minimal and they primarily cause the release of endogenous pyrogens by the host. Box 5-2 lists some of the more important known exogenous pyrogens.

Box 5-2 Exogenous Pyrogens

From Miller JB: Hyperthermia and fever of unknown origin. In Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC, editors: Textbook of veterinary internal medicine, ed 6, St Louis, 2005, Saunders.