Chapter 117 Hypercoagulable States

HEMOSTASIS OVERVIEW

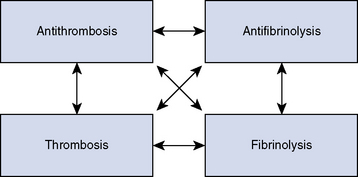

Hemostasis is a remarkable interaction of numerous plasma proteins and cells with the singular purpose of forming a seal over damage in the intravascular space and dissolving the patch once vascular healing has taken place. The complexity of these interactions is significant, with countless possible interactions, positive and negative feedback loops among hosts of contributing factors. A modern view of hemostatic function partitions these interactions into a four-quadrant system, with interactions possible among all four major hemostatic forces (Figure 117-1). The purpose of each quadrant is unique. Thrombosis factors work in concert to cause the formation of a platelet-fibrin meshwork seal of the vessel injury. The goal of antithrombotic forces is to limit the development of thrombus or clot in the area of injury and to maintain normal blood fluidity through the remainder of the uninjured vascular space (local control). Fibrinolytic forces will gradually destroy or break down the clot when vessel repair is complete, to allow recanalization of the vessel and return of blood flow. Loss of local control of fibrinolysis would ultimately lead to an inability to form a clot anywhere, so antifibrinolytic factors serve to isolate fibrinolysis to the area of injury or thrombus and maintain local control. In addition, antifibrinolytic factors help protect the clot from fibrinolysis while vessel repair is ongoing. Each quadrant in this system has several important individual molecules (both hemostatic and inflammatory), which interact with the relevant cells involved to achieve their underlying purposes.

MACROVASCULAR THROMBOSIS

As previously mentioned, the most common forms of macrovascular thrombosis in small animal veterinary patients are FATE and pulmonary thromboembolism. Pulmonary thromboembolism is discussed further in Chapter 27, Pulmonary Thromboembolism. The clinical signs of macrovascular thrombosis will depend on the anatomic location of the thrombus. Thrombi often are formed in one location and then travel down the vascular system to lodge in a distant location (thromboembolism), where they cause injury via ischemia and associated organ dysfunction. Treatment of macrovascular thrombosis includes administration of anticoagulant drugs, management of underlying disease processes, and possibly thrombolysis. Anticoagulants such as heparin or aspirin are given in an effort to prevent any progression of the thrombus or new thrombus formation (see Chapter 187, Anticoagulants). Treatment of any predisposing underlying disease is very important to prevent further thrombus formation. Administration of thrombolytic drugs aims to cause complete dissolution of the clot and subsequent resolution of the signs. Thrombolytic therapy is not universally successful, can be associated with life-threatening hemorrhage, and when successful may cause life-threatening hyperkalemia as a consequence of postischemia syndrome. Chapter 188, Thrombolytic Agents, discusses thrombolytic therapy in more detail.

MICROVASCULAR THROMBOSIS

Coagulopathy of Systemic Inflammation

DIC is an umbrella diagnosis that has been used in the past to describe a number of paradoxical thrombohemorrhagic disorders of humans. An international consensus defined DIC as “an acquired syndrome characterized by the intravascular activation of coagulation with loss of localization arising from different causes. It can originate from and cause damage to the microvasculature, which if sufficiently severe, can produce organ dysfunction.”6 A similar syndrome is present in many veterinary species, and the term DIC was also adopted for use in veterinary patients. Numerous conditions have been associated with DIC in veterinary patients (Box 117-1), but the pathophysiology is best understood for the coagulopathy associated with SIRS and sepsis.7 Arguably, cytokine activation of inflammation or dysregulation of inflammatory signals are the only causes of DIC and are the unifying processes that link all of the disparate causes of DIC.