CHAPTER | 9 Hereditary, Congenital, and Acquired Alopecias

Alopecia X (adrenal sex hormone imbalance, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, castration-responsive dermatosis, adult-onset hyposomatotropism, growth hormone–responsive dermatosis, pseudo-Cushing’s disease, follicular arrest of plush-coated breeds, hair cycle arrest)

Alopecia X (adrenal sex hormone imbalance, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, castration-responsive dermatosis, adult-onset hyposomatotropism, growth hormone–responsive dermatosis, pseudo-Cushing’s disease, follicular arrest of plush-coated breeds, hair cycle arrest) Canine Recurrent Flank Alopecia (seasonal flank alopecia, cyclic flank alopecia, cyclic follicular dysplasia)

Canine Recurrent Flank Alopecia (seasonal flank alopecia, cyclic flank alopecia, cyclic follicular dysplasia)Excessive Shedding

Alopecic Breeds

Treatment and Prognosis

FIGURE 9-3 Alopecic Breeds.

This Chinese Crested demonstrates the characteristic pattern of alopecia typical of this breed.

FIGURE 9-5 Alopecic Breeds.

A Sphinx cat, demonstrating the almost total alopecia typical of this breed.

FIGURE 9-11 Alopecic Breeds.

Over time, the occluded follicles form milia, which appear as white, papular lesions.

Canine Hypothyroidism

Diagnosis

Treatment and Prognosis

FIGURE 9-15 Canine Hypothyroidism.

Mild alopecia on the bridge of the nose may be an early lesion of hypothyroidism.

FIGURE 9-16 Canine Hypothyroidism.

Alopecia and hyperpigmentation with no evidence of secondary superficial pyoderma on the trunk.

FIGURE 9-22 Canine Hypothyroidism.

Severe fading of the hair coat with partial alopecia in a hypothyroid Irish Setter.

FIGURE 9-23 Canine Hypothyroidism.

Same dog as in Figure 9-22. The extremely faded hair coat also demonstrates partial alopecia (the matting is not typical of this disease).

FIGURE 9-24 Canine Hypothyroidism.

Same dog as in Figure 9-22. Faded hair is apparent on the dorsal surface of the foot. Note the abnormal nails, which developed as a result of the metabolic effects of hypothyroidism.

FIGURE 9-25 Canine Hypothyroidism.

Same dog as in Figure 9-22. Abnormal nails developed as a result of the abnormal metabolism caused by the disease.

FIGURE 9-26 Canine Hypothyroidism.

Generalized fading caused by the lack of normal follicular cycling and hair renewal.

Canine Hyperadrenocorticism (Cushing’s disease)

Diagnosis

ACTH stimulation test (cortisol): an exaggerated poststimulation cortisol level is highly suggestive of endogenous hyperadrenocorticism, but false-negative and false-positive results can occur. In iatrogenic cases, an inadequate response to ACTH stimulation is typical. Note: Reconstituted cosyntropin (ACTH solution) can be stored frozen at −20°C in plastic syringes for up to 6 months with no adverse effects on its bioactivity.

ACTH stimulation test (cortisol): an exaggerated poststimulation cortisol level is highly suggestive of endogenous hyperadrenocorticism, but false-negative and false-positive results can occur. In iatrogenic cases, an inadequate response to ACTH stimulation is typical. Note: Reconstituted cosyntropin (ACTH solution) can be stored frozen at −20°C in plastic syringes for up to 6 months with no adverse effects on its bioactivity. ACTH stimulation test (17-hydroxyprogesterone): exaggerated basal and poststimulation 17-hydroxyprogesterone levels may be seen in endogenous hyperadrenocorticism, but false-negative and false-positive results can occur. 17-Hydroxyprogesterone, a progestin, is an adrenal gland–produced precursor of cortisol.

ACTH stimulation test (17-hydroxyprogesterone): exaggerated basal and poststimulation 17-hydroxyprogesterone levels may be seen in endogenous hyperadrenocorticism, but false-negative and false-positive results can occur. 17-Hydroxyprogesterone, a progestin, is an adrenal gland–produced precursor of cortisol. Low-dose (0.01 mg/kg) dexamethasone suppression test: inadequate cortisol suppression is highly suggestive of endogenous hyperadrenocorticism, but false-negative and false-positive results can occur. Suppression at 4 hours followed by escape from suppression at 8-hour sampling is characteristic of PDH.

Low-dose (0.01 mg/kg) dexamethasone suppression test: inadequate cortisol suppression is highly suggestive of endogenous hyperadrenocorticism, but false-negative and false-positive results can occur. Suppression at 4 hours followed by escape from suppression at 8-hour sampling is characteristic of PDH. High-dose (0.1 mg/kg) dexamethasone suppression test: used to help differentiate between adrenal neoplasia and pituitary-dependent hyperadrenocorticism. Lack of cortisol suppression is suggestive of adrenal neoplasia, whereas cortisol suppression suggests pituitary disease.

High-dose (0.1 mg/kg) dexamethasone suppression test: used to help differentiate between adrenal neoplasia and pituitary-dependent hyperadrenocorticism. Lack of cortisol suppression is suggestive of adrenal neoplasia, whereas cortisol suppression suggests pituitary disease.Treatment and Prognosis

Mitotane for adrenal tumors: one should give 50 mg/kg PO every 24 hours with food for 7 to 14 days. An ACTH stimulation test is performed every 7 days. If inadequate cortisol suppression persists, increase the mitotane dosage to 75–100 mg/kg/day for an additional 7 to 14 days, while monitoring with ACTH stimulation tests weekly. When adequate adrenal suppression is demonstrated, maintenance mitotane therapy is initiated as described below.

Mitotane for adrenal tumors: one should give 50 mg/kg PO every 24 hours with food for 7 to 14 days. An ACTH stimulation test is performed every 7 days. If inadequate cortisol suppression persists, increase the mitotane dosage to 75–100 mg/kg/day for an additional 7 to 14 days, while monitoring with ACTH stimulation tests weekly. When adequate adrenal suppression is demonstrated, maintenance mitotane therapy is initiated as described below. To maintain remission after mitotane induction, mitotane PO with food 50 mg/kg administered once weekly, or 25 mg/kg twice weekly. Dogs that relapse during maintenance therapy should be reinduced with daily mitotane for 5 to 14 days or until recontrolled, then maintained with 62 to 75 mg/kg once weekly, or 31 to 37.5 mg/kg twice weekly. A great deal of patient variability occurs, requiring close monitoring.

To maintain remission after mitotane induction, mitotane PO with food 50 mg/kg administered once weekly, or 25 mg/kg twice weekly. Dogs that relapse during maintenance therapy should be reinduced with daily mitotane for 5 to 14 days or until recontrolled, then maintained with 62 to 75 mg/kg once weekly, or 31 to 37.5 mg/kg twice weekly. A great deal of patient variability occurs, requiring close monitoring.

FIGURE 9-30 Canine Hyperadrenocorticism.

Same dog as in Figure 9-29. The potbellied appearance and alopecia are apparent.

FIGURE 9-31 Canine Hyperadrenocorticism.

Same dog as in Figure 9-29. Generalized seborrhea sicca can be secondary to numerous underlying diseases but was caused by hyperadrenocorticism in this dog.

FIGURE 9-33 Canine Hyperadrenocorticism.

Close-up of the dog in Figure 9-32. As tissue wasting progressed, the scar became thin and the tissue was pulled apart.

FIGURE 9-34 Canine Hyperadrenocorticism.

The papular rash was caused by secondary superficial pyoderma.

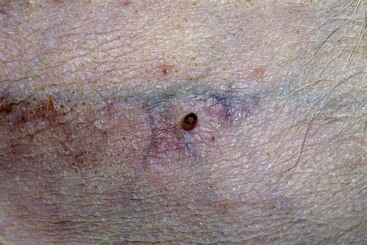

FIGURE 9-37 Canine Hyperadrenocorticism.

Extensive calcinosis cutis covering the dorsum of a dog with iatrogenic Cushing’s disease.

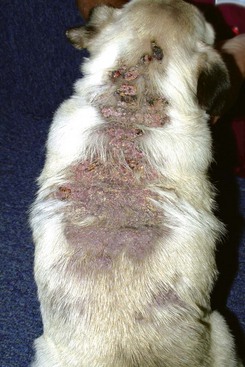

FIGURE 9-42 Canine Hyperadrenocorticism.

Calcinosis cutis with a severe inflammatory dermatitis in the inguinal skin fold.

FIGURE 9-43 Canine Hyperadrenocorticism.

Close-up of the dog in Figure 9-42. The erythematous, papular plaque was caused by a combination of calcinosis cutis and secondary infection.

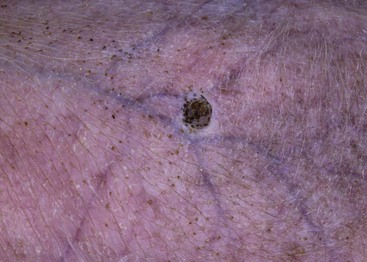

FIGURE 9-44 Canine Hyperadrenocorticism.

Symmetrical truncal alopecia in a dog with hyperadrenocorticism.

FIGURE 9-45 Canine Hyperadrenocorticism.

Same dog as in Figure 9-44. The sparse hair coat was bilaterally symmetrical. This dog was mildly pruritic because of a secondary superficial pyoderma.

FIGURE 9-46 Canine Hyperadrenocorticism.

Ventral alopecia with a distended abdomen in a dog with an adrenal tumor.

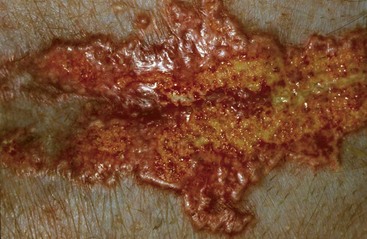

FIGURE 9-47 Canine Hyperadrenocorticism.

Phlebectasia (an erythematous papular lesion) on the abdomen of a dog with Cushing’s disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree