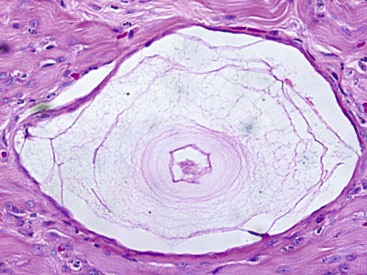

Chapter 273 Hepatozoon americanum is a tick-borne parasite infecting domestic dogs and coyotes in the United States and is the causative agent of American canine hepatozoonosis (ACH), a painful, debilitating, and often fatal clinical syndrome. ACH is considered an emerging disease, and recent molecular data obtained from clinically suspicious dogs presented to veterinarians throughout the United States in 2006 to 2008 indicate that the disease is no longer limited to south-central and southeastern states (Li et al, 2008). Thus veterinarians all over the United States, regardless of location, must recognize clinical signs of ACH. Although the disease is incurable, ACH can be well managed with drug therapy in many patients, especially if treatment begins soon after initial presentation of clinical signs (Macintire et al, 2001). The accepted primary route of H. americanum transmission to domestic dogs and wild canids is ingestion of Amblyomma maculatum (Gulf Coast tick) that contain sporulated H. americanum oocysts. The ingestion of infected ticks is thought to be a result of grooming or inadvertent ingestion of infected ticks infesting prey or scavenged animals. In addition to the conventional route, recent experiments have confirmed transmission of H. americanum to domestic dogs via their consumption of cystozoites contained in tissues harvested from experimentally infected paratenic hosts (Johnson et al, 2009). Predator-prey relationships are important in the lifecycles of many Hepatozoon spp. and likely are involved in H. americanum transmission cycles. H. americanum zoites are liberated within the canine alimentary tract and disperse by an unknown route to other tissues, particularly striated muscle, to undergo merogony. Several weeks after experimental infection, meronts of H. americanum can be observed within leukocytes situated between individual muscle fibers in stained histologic preparations of muscle biopsy samples. Meront-containing leukocytes are encysted within host cell–derived concentric layers of mucopolysaccharide, which resemble the layers of an onion. The characteristic lesions thus are termed “onion skin” cysts (Figure 273-1). Meronts increase in size as they mature and eventually rupture host cells to release merozoites, which then penetrate cyst walls and result in localized inflammatory reactions that often progress to pyogranulomata. Liberated merozoites invade new host leukocytes to form additional meronts or develop into gamonts, the sexually differentiated, peripherally circulating stages of parasite that are infective to feeding larval and nymphal A. maculatum (Panciera and Ewing, 2003). ACH is diagnosed most often in dogs in rural areas, especially if kenneled outdoors or allowed to roam, that are not maintained diligently with acaricidal compounds and that prey on other animals. Clinical signs are a result of parasite merogonic cycles within tissues and associated inflammatory reactions and are seen as soon as 3 to 5 weeks after exposure in experimentally infected dogs (Panciera and Ewing, 2003). Dogs often are presented with fever (102.7° F to 105.6° F) that does not resolve with antibiotic treatment, a stiff and painful gait, lameness, ataxia, generalized weakness, reluctance to move, lethargy, and depression. Despite obvious discomfort, dogs often continue to eat and drink, but sometimes only when food and water are placed directly in front of them. However, weight loss still may be noted, which is a result of increased inflammatory processes, and marked muscle atrophy is not uncommon (Little et al, 2009; Medici and Heseltine, 2008; Panciera and Ewing, 2003; Potter and Macintire, 2010; Vincent-Johnson, 2003). A consistent feature of the syndrome is a copious mucopurulent ocular discharge. In addition, uveitis, retinal scarring, hyperpigmentation, and papilledema may be evident upon ophthalmic exam (Medici and Heseltine, 2008; Potter and Macintire, 2010). Although some dogs continue to decline after initial onset of clinical signs, other patients endure a waxing and waning course of disease, with obvious clinical signs spontaneously abating only to recur a few months later. The cyclic presentation and resolution of apparent illness is ascribed to interims of active and arrested parasite merogony, respectively (Macintire et al, 2001; Potter and Macintire, 2010).

Hepatozoon americanum Infections

Pathogenesis

Clinical Manifestations

Clinical Signs

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree