Chapter 15 Healing of the Ruptured Eardrum

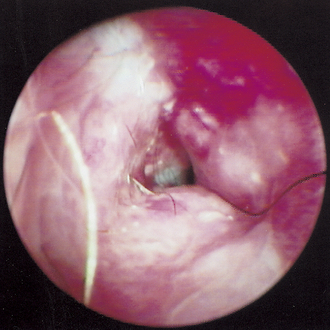

Veterinarians are often faced with the problem of ruptured eardrums. It is difficult to assess the eardrum in a small animal because most otoscopes do not provide good lighting or adequate magnification. Many cases of otitis externa result in an ear canal that is inflamed, stenotic, and full of exudates that impede the visual determination of the integrity of the eardrum (Figure 15-1).

Causes of Rupture

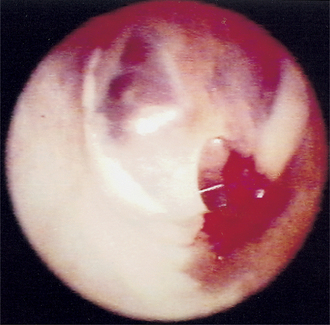

Traumatic perforations of the tympanic membrane also occur as the result of either excessive fluid pressure achieved during flushing of the ear canal or traumatic use of instruments during cleaning of the ear canal (Figure 15-2). Myringotomy, a traumatic perforation of the eardrum, may be iatrogenic or may be intentionally induced in therapy for otitis media.

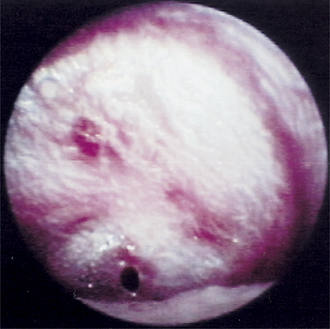

Cats with respiratory disease may rupture their eardrums through sneezing. Increased air pressure builds within the eustachian tube during the violent act of sneezing, and that air pressure is transmitted through the eustachian tube to the middle ear cavity. When the pressure in the tympanic bulla exceeds 300 mm Hg, the eardrum ruptures (Figures 15-3 and 15-4).

Nasopharyngeal polyps found in dogs and cats either grow along the eustachian tube toward the oropharynx or enlarge into the tympanic bulla. A large polyp within the tympanic bulla pushes against the eardrum, creating pressure necrosis, and its continued growth results in the ultimate destruction of the tympanic membrane (Figure 15-5).

Healing Process

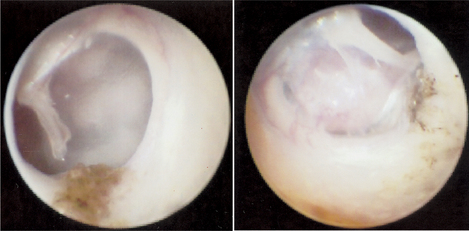

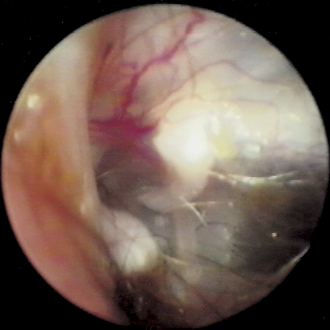

As discussed elsewhere, the germinal epithelium for the epidermal layer of the tympanic membrane is located in the area of the manubrium of the malleus and grows radially toward the annulus of the tympanic membrane from that location. Vascular supply to the germinal epithelium is derived from the blood vessels branching from the pars flaccida along the “vascular strip.” If the malleus is preserved and the vascular strip is not compromised, the process of healing can continue (Figure 15-6).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree