Chapter 1 Handling and Examining Sheep and Goats

Physical Examination

Signalment and History

Housing—including shelter type, pasture size and rotation, and pasture availability

Feeding—including type of feed, feeding regimen, water source and any recent changes in feeds or feeding regimen, and availability of browse

Animal contact information—including recent introductions to the herd, animal source for recently purchased animals, transportation to shows, fairs, or other facilities, and any contact with non–farm origin animals.

Herd health information—including the status of diseases monitored at the herd level such as caprine arthritis encephalitis (CAE) virus infection, caseous lymphadenitis, or internal parasitism; results of routine surveillance testing; previous diseases present on the premises; any vaccination programs or anthelminthic, anticoccidial, or routine treatments completed on the farm; and any standard operating procedures (SOPs) that may be in place

Intended animal use (pet, fleece, leather, meat, milk)—dictating all aspects of care and management

Distance Examination

Animals that are lagging behind the group or have separated themselves from the group require closer scrutiny. In addition, abnormal respiratory pattern, droopy ears, nasal discharge, and fecal staining of the perineum may be signs that the affected animal is in need of further evaluation. Initial assessments of lameness (altered posture or gait), body condition, conformation, body symmetry, and neurologic status also can be made during a distance examination. This examination also may allow the veterinarian to identify additional animals in need of care that have not been observed by the producer. Once the distance examination is complete, the animal can be appropriately restrained for a hands-on physical examination.

Body Condition Score

Determination of body condition score (BCS) is an effective tool for managing both individual animals and herds (Chapter 2). In an individual animal, low BCS may indicate disease or poor access to feed. In a flock or herd, a trend toward low BCSs may be indicative of inadequate feed quantity or quality or of management-related diseases such as internal parasitism. A preponderance of low BCSs should be a trigger for investigating management diseases or introducing supplemental feeding. Conversely, a preponderance of high scores may indicate the need to decrease supplemental feeding.

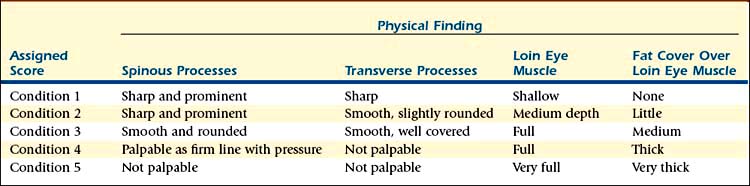

Body condition scoring requires hands-on assessment of the animal. This is not a visual examination. Evaluation of the muscle and fat covering over the lumbar region between the dorsal and transverse spinous processes as well as the fat covering on the sternum is used to determine BCS. Tables and charts with pictures are available and are useful tools for reference for scoring. Sheep and goats are scored on a 1 to 5 system, with 1 representing emaciation and 5 representing extreme obesity (Table 1-1). Half-scores (in 0.5-point increments) may be assigned when an animal’s condition falls between two traditional scores. Ideally, BCS should be between 2.5 and 4.0, depending on the animal’s stage in the reproductive and production cycles.

Light-skinned breeds or animals with severe liver disease may suffer from photodermatitis or photosensitization. In such instances, erythema and edema accompanied by pruritus and severe pain may be noted on lightly haired or lightly wooled skin. In severe cases, aseptic necrosis and sloughing of skin may be present. In colder months, frostbite may lead to alopecia with swelling and erythema; severe cases may be characterized by dry gangrene, necrosis, or sloughing of skin of distal extremities.

Examination by Body Systems and Structures

Head and Neck

Evaluation of the oral and conjunctival membranes is not complete without inspection for color change and estimate of perfusion. This aspect of the examination is important for parasite control with use of the FAMACHA method (see Chapter 6). Some breeds may have pigmented oral mucous membranes, making these assessments difficult. In such animals, preputial or vulvar membranes may be used instead. Pale membranes may indicate anemia, most likely caused by Haemonchus contortus infestation. Jaundice may be present in animals with liver disease or, alternatively, those that have undergone a hemolytic event, such as that related to copper toxicity. Reddish congested membranes may be indicative of fever, septicemia, or toxemia.

The oral cavity should be evaluated for structural abnormalities and smell. The teeth can be used to estimate the age of the animal (Chapter 4). Prognathism and brachygnathism are readily apparent on inspection of the head. Subtler lesions, however, will be more evident when the mouth is open and the maxilla and mandible can be better evaluated for alignment. Cleft palate can be seen as a gap in the dorsal mouth where the hard palate failed to fuse. In animals in which the mouth cannot be opened wide enough for visualization of the hard palate, sweeping a finger over the palatal surface should reveal any defect. A normal hard palate in a ruminant animal has a rough feel similar to that of corrugated cardboard.

Teeth should be evaluated for wear and the presence of disease. Animals with abnormal wear patterns or poor dentition (no teeth, lost teeth) may have difficulty eating and maintaining body condition, particularly in situations involving competition for food. Both sheep and goats also can be aged on the basis of eruption of the dentition. Age typically is estimated using the time of eruption and wear patterns present on the incisors. After the permanent incisors have erupted, aging by dentition becomes less accurate owing to the effects of certain feedstuffs and behavior on tooth wear. Eruption times for sheep and for goats are similar, although some individual and breed variability has been documented.

Deciduous incisors erupt as follows:

Permanent incisors erupt as follows:

Cardiovascular System

Rate, rhythm, character, and intensity of the heart sounds should be assessed. The normal heart rate ranges between 70 and 90 beats/minute in an adult goat and 70 and 80 beats/minute in an adult sheep (Table 1- 2). Heart rate in kids and lambs is more variable at 90 to 150 beats/minute and 80 to 130 beats/minute, respectively (Table 1-3). Synchrony of the heart beat and peripheral pulse can be assessed by simultaneous auscultation of the heart and palpation of the femoral artery on the medial aspect of the pelvic limb in the proximal third of the distance between the hip and stifle.

TABLE 1-2 Temperature, Pulse, and Respiratory Rates in Adult Sheep and Goats

| Parameter | Sheep | Goats |

|---|---|---|

| Rectal temperature (° F) | 102-103.5 | 100.5-103.5 |

| Rectal temperature (° C) | 39-40 | 38-40 |

| Pulse (beats/minute) | 70-80 | 70-90 |

| Respiration (breaths/minute) | 12-20 | 15-30 |

TABLE 1-3 Temperature, Pulse, and Respiratory Rates in Lambs and Kids

| Parameter | Lambs | Kids |

|---|---|---|

| Rectal temperature (° F) | 102.5-104 | 102-104 |

| Rectal temperature (° C) | 39.5-40.5 | 39.5-40.5 |

| Pulse (beats/minute) | 80-130 | 90-150 |

| Respiration (breaths/minute) | 20-40 | 20-40 |

Respiratory System

The clinician can determine the respiratory rate by observing the movements of the costal arch or nostrils at a distance. The average respiratory rate for an adult goat is 15 to 30 breaths/minute, and for an adult sheep, 12 to 20 breaths/minute (see Table 1-2); kids and lambs have a respiratory rate of 20 to 40 breaths/minute (see Table 1-3). An increased respiratory rate may be a sign of excitement, high environmental temperature or humidity, pain, fever, respiratory or cardiovascular disease, or respiratory compensation for metabolic acidosis. A decreased respiratory rate may result from respiratory compensation for metabolic alkalosis. The clinician should carefully look for and note signs of dyspnea or respiratory distress, including tachypnea, extended head and neck, open-mouth breathing, flaring nostrils, abducted elbows, exaggerated abdominal movements, and anal pumping.

The clinician should auscultate the trachea for wheezing (as heard with tracheal collapse or an obstructive lesion) and crackling sounds (characteristic of tracheitis). A cough sometimes can be elicited by palpating the larynx and squeezing the trachea. A normal animal may cough once or twice, whereas a diseased animal will cough repeatedly after tracheal compression. Upper airway disease (e.g., rhinitis, tracheitis, foreign body, compressive lesion) usually is characterized by a loud, harsh, dry, nonproductive cough of acute onset. Affected animals do not swallow after coughing. Lower airway disease usually is characterized by a chronic, soft, productive cough. Animals with lower airway disease typically cough infrequently and will swallow after coughing. Examples of lower airway disease are chronic pneumonia, lung abscess, and lungworm infection. Coughing up blood suggests aspiration pneumonia or pharyngeal abscess (Chapter 7).

Gastrointestinal System

Because the gastrointestinal system occupies the major portion of the abdominal cavity, abdominal contour is an important part of the examination of this body system. Animals should be observed from behind to compare both sides. The presence of the rumen on the left causes a natural mild asymmetry in abdominal contour in both sheep and goats. The presence of a heavy wool or hair coat can mask abnormalities in contour, so these animals should be palpated for normal contour. The clinician should evaluate all areas of the abdomen, alternating percussion and ballottement. Rumen contractions can be auscultated and palpated in the left paralumbar fossa. In healthy sheep and goats, occurrence of one to two primary rumenal contractions (ingesta mixing) and one secondary contraction (eructation) per minute is characteristic (Table 1-4). In healthy animals, a gas cap will be present dorsally on clinical examination, with the fiber mat sitting directly below. Normal fiber mat should be firm but indentable. The normal fluid layer will lie below the fiber mat. Decreased rumen contraction rate and abnormal striation of contents may be due primarily to indigestion or disease of the rumen. However, rumen contraction rate often is abnormal in animals as a result of other, nongastrointestinal illnesses. The presence of a “ping” indicates a fluid-gas interface, typically in a distended viscus. Secussable fluid may be trapped within a viscus or free in the abdomen. Large abdominal masses or fetuses may be detectable by ballottement, depending on size.

TABLE 1-4 Some Physiologic Parameters in Sheep and Goats

| Parameter | Sheep | Goats |

|---|---|---|

| Rumen contraction rate (number/minute) | 1-2 | 1-2 |

| Age at puberty (months) | 5-12 | 4-12 |

| Estrus duration (hours) | 36 | 12-24 |

| Estrus cycle (days) | 16-17 | 18-23 |

| Gestation (days) | 147 | 150 |

| Average birth weight (lb) | Breed-dependent | Breed-dependent |

| Single | 8-13 | |

| Twins | 7-10 | |

| Dairy | 6.5-9.5 | |

| Meat | 6-15 | |

| Fleece weight (lb) | 7-15 |

The normal rectal temperature in sheep and goats ranges between 102° and 103.5° F and 100.5° and 104.0° F, respectively (see Tables 1-2 and 1-3). Hyperthermia may result from elevated environmental temperature and humidity, stress and excitement, or inflammatory disease. Hypothermia may occur in malnourished or older animals. Diseases of the rectum are uncommon in mature sheep and goats. Sheep with excessively short tail docks or certain feeding regimens are prone to rectal prolapse. Fecal consistency should be evaluated. Of note, increased fecal water is attributable to many physiologic processes and is not always a sign of infectious disease. Fecal soiling of the perineum and the back of the hindlegs is a consistent finding in animals with persistent diarrhea.

The abdomen of young kids should be palpated for pain and swelling. Particular attention should be paid to both the internal and external umbilical structures. The remnants of the umbilical vein can be palpated in the abdomen moving cranially toward the liver, whereas the remnants of the urachus and both umbilical arteries course caudally toward the urinary bladder. Pain in any remnant with or without swelling is indicative of infection. The perineum and pelvis of lambs should be evaluated for fecal staining. Diarrhea can quickly lead to life-threatening acid-base and electrolyte abnormalities in young kids and lambs. In neonates, the presence or absence (atresia ani) of the anus should be noted (Chapter 5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree