Chapter 5 Hamsters and guinea pigs

Hamsters

Introduction

The total numbers of Syrian hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) used in biomedical research is much less than the numbers of rats and mice used, however, the Syrian hamster is an important research subject. Hamsters are used in specialized research situations where the use of their cheek pouch for tumor induction and transplantation has contributed significantly to carcinogenesis research (Strandberg, 1987). Hamsters are also used in contract research laboratories and pharmaceutical companies for occasional studies. Information about the incidence of spontaneously occurring lesions is essential if Syrian hamster is to be used in acute and chronic toxicity studies (Pour et al 1976a). The interpretation of tumor incidences in hamster carcinogenicity studies depends on a good knowledge of the background neoplastic and non-neoplastic lesions of the species involved (Pour et al 1976a).

Hamsters are occasionally chosen as the candidate species for carcinogenicity studies in preclinical studies. Reasons include the fact that hamsters are less sensitive in developing olfactory mucosa toxicity (Toth et al 1961) and hamsters have a low incidence of spontaneous neoplastic lesions (Kamino et al 2001a).

Cardiovascular system

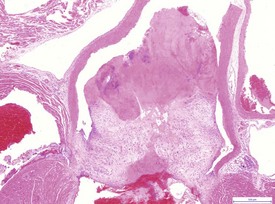

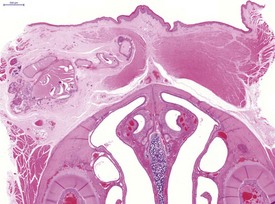

Atrial thrombosis, secondary to heart failure, is seen commonly in older hamsters (Gad 2007a). This lesion generally occurs in the left atrium and auricle and may cause dilatation of the left ventricle (Fig. 5.1). Female hamsters are more commonly affected than male hamsters and the syndrome may be associated with amyloidosis (Percy & Barthold 2007). Atrial thrombosis may be associated with myocardial degeneration and fibrosis as well as medial degeneration and calcification of the coronary arteries (Percy & Barthold 2007). In addition, vegetative endocarditis or aortic valve thrombosis has also been observed in older hamsters (Fig. 5.2). Vascular calcinosis has been noted in the aorta and coronary and renal arteries; however, this lesion is thought to be related to diet (Pour et al 1976d). Fibrinoid degeneration of arterioles may also be observed in aging hamsters (Percy & Barthold 2007).

Hemolymphoreticular system

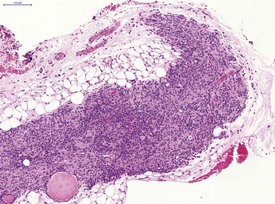

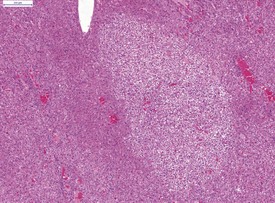

In common with other laboratory animals, hamsters display atrophy and involution of the thymus as they reach adulthood (Fig. 5.3).

Respiratory system

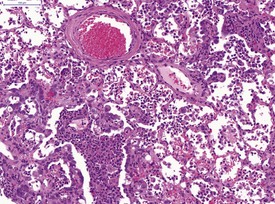

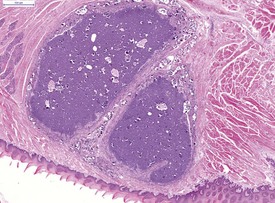

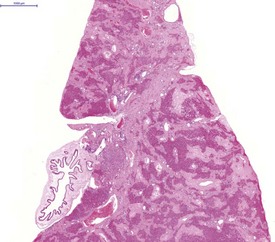

The severe cardiac insufficiency caused by atrial thromboses or aortic valve thromboses causes chronic pulmonary congestion and this results in an increase in haemosiderin-laden, alveolar macrophages within the alveoli of the lung (Fig. 5.4). Neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia occurs in small foci in the bronchioles and within the trachea (Fig. 5.5). The presence of spontaneous C-cell or neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia or benign or malignant tumors of these cells in the larynx (Pour et al 1985) or the trachea (Ernst et al 1995) may be unique to hamsters. The frequency varies considerably between colonies of hamsters (Mohr et al 1996). Pour and co-workers (1985) reported an incidence of 9% in the larynx of Syrian hamsters. Ernst and co-workers have confirmed the neuroendocrine origin of these cells and stated that they occur in the larynx and upper trachea. The proliferation of neuroendocrine cells in the larynx and upper trachea is first observed at 15 months of age in Syrian hamsters and it is difficult to differentiate between hyperplasia, benign tumor and malignant tumor involving these cells (Mohr et al 1996). The cytoplasm of the neuroendocrine cells tends to be clear with large, central nuclei (Mohr et al 1996). Mitotic figures are rare (Mohr et al 1996). Ernst et al 1995 demonstrated that the neuroendocrine cells in these laryngeal and tracheal locations are positive for calcitonin, calcitonin gene related peptide, neuron-specific enolase (NSE), and serotonin using immunohistochemistry. Benign tumors of neuroendocrine cells do not display invasion while malignant tumors of these cells demonstrate submucosal and lumenal invasion and metastasis to the lung (Ernst et al 1995). The term C-cell hyperplasia rather than neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia is now favored since the origin of these cells is thought to be the C-cells from the thyroid. In addition, alveolar histiocytosis may be observed in the lungs of older hamsters (Percy & Barthold 2007).

Gastrointestinal system

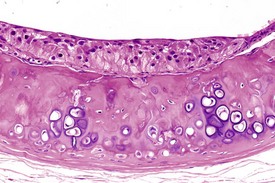

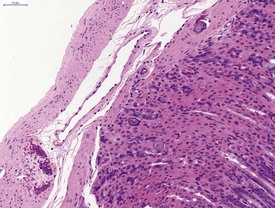

Cyst formation and mineralization in the hard palate of a hamster is occasionally observed (Fig. 5.6). Mineralization in the tongue of a hamster is also noted (Fig. 5.7). Mineralization of the gastric mucosa is observed commonly in hamsters (Fig. 5.8). Ulcers and erosions are observed commonly in the hamster forestomach as well as in the glandular region (Pour et al 1976a & b) (Fig. 5.9). Herniation of gastric glands into the tunica muscularis occurs in the hamster stomach (Fig. 5.10). Tumors of granular cells and areas of proliferation composed of granular cells in the intestinal walls of white hamsters have been described by Pour and co-workers (1973). This finding may be observed in the serosa of the small and large intestine.

Liver and biliary system

In the liver, intranuclear inclusions are a non-specific background lesion and the cause is not known; however, the inclusions are thought to be formed by invagination of nuclear membrane with incorporation of some cell cytoplasm. The inclusions are weakly eosinophilic with H&E, PAS-negative, 5–8 micrometers in diameter, homogeneous or granular in appearance and usually eccentrically located within the nucleus. The nuclei containing the inclusions are frequently enlarged and have an irregular wrinkled profile (Fig. 5.11).

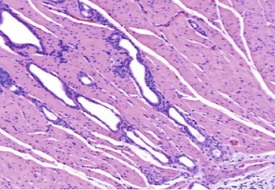

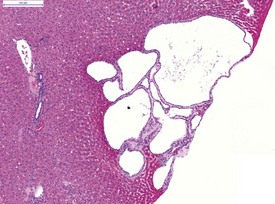

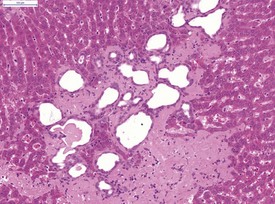

Liver cysts are common in the hamster and are thought to derive from bile ducts (Gad 2007a) (Fig. 5.12). Polycystic liver disease may occur in hamsters and is characterized by multiple hepatic cysts observed in older animals (Percy & Barthold 2007). Cysts are most common in the liver and epididymis as well as in the seminal vesicles and pancreas (Percy & Barthold 2007).

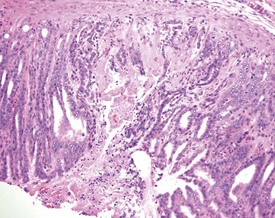

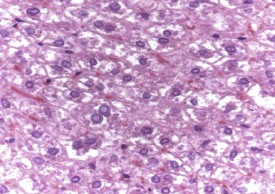

Atrophy of the adjacent hepatocytes, hemosiderin deposition, bile duct hyperplasia and periportal lymphocytes may be observed in conjunction with the liver cysts (Percy & Barthold 2007). Clear-cell foci are a normal background change in the hamster liver (Kamino et al 2001b) (Fig. 5.13). In common with rats and mice, bile-duct hyperplasia is observed in the hamster liver (Fig. 5.14) (Percy & Barthold 2001, 2007). Bile-duct proliferation forms part of the hepatic cirrhosis complex in hamsters, which includes periportal fibrosis, bile-duct proliferation, nodular hepatocellular proliferation, degeneration, necrosis and a mixed inflammatory-cell infiltrate (Percy & Barthold 2007).

Amyloidosis occurs frequently in hamsters, particularly in older animals and in female animals. Testosterone administration will inhibit the occurrence of amyloidosis in female hamsters (Percy & Barthold 2007). The liver, kidneys, adrenals and gonads are the most commonly affected organs. In the liver, amyloid deposition is observed around the portal areas, within blood vessel walls and within the sinusoids (Fig. 5.15). Amyloidosis is an important cause of renal failure in hamsters (Percy & Barthold 2007). Gall bladder cholelithiasis and submucosal lymphocyte aggregates are occasionally observed in the hamster gall bladder (Fig. 5.16).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree