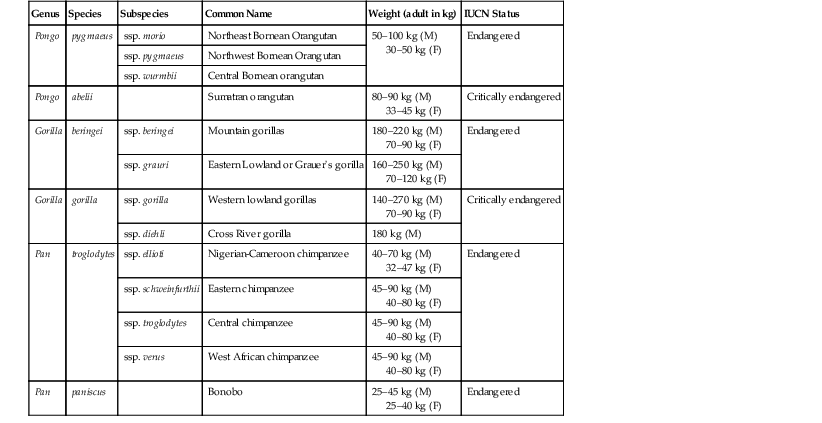

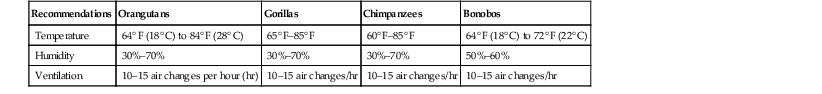

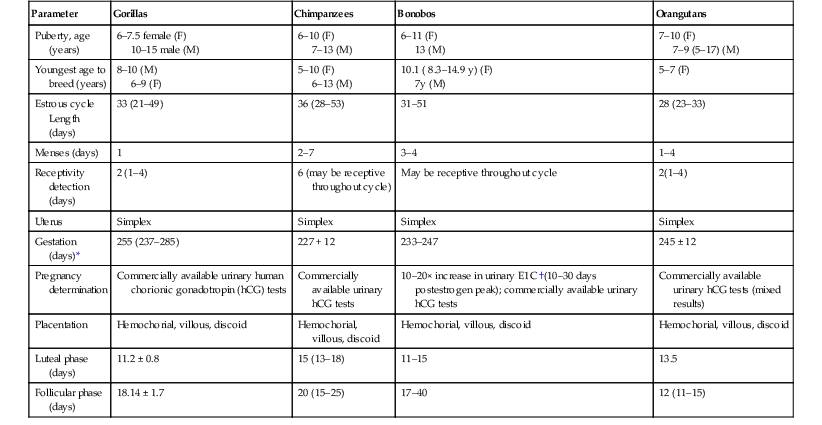

Hayley Weston Murphy Great apes are a taxonomic family of primates classified as Hominidae and include seven living species in four genera: chimpanzees and bonobos (Pan), gorillas (Gorilla), orangutans (Pongo), and humans (Homo).13 The dental formula for the great apes is: (incisor 2/2, canine 1/1, premolar 2/2, molar 3/3) × 2 = 32. The great apes originate from equatorial Africa (gorillas, chimpanzees, and bonobos) and Southeast Asia (orangutans) and are characterized by the absence of tails and their intelligence, strength, and large size. Table 38-1 gives an overview of their status in the wild. Significant threats to wild great ape populations include the hunting of apes for sale as commercial meat products, widespread habitat loss, and infectious disease threats. Outbreaks of Ebola virus, respiratory disease epidemics, and bacterial and parasitic illnesses have resulted in high morbidity and mortality events, often in association with close contact with humans.15–17,31,34,36,41,46,48,49,51 TABLE 38-1 Genus, Species, and Status in the Wild13 F, Female; M, male;. The great apes are intelligent animals and have great strength and varied facial and vocal expressions. They all have laryngeal sacs, which are thought to be used for vocal resonations; these sacs vary in size and complexity, expanding with age into the pectoral, clavicular, and axillary regions. Mature male orangutans have extensive laryngeal sacs that extend around the mandible toward the ears and cheeks and along the thoracic wall.21 Orangutan males are the only great apes that develop cheek pads (flanges), which are composed of fat and fibrous tissue.2 See Figures 38-1, 38-2, 38-3 for examples of adult male Bornean, Sumatran, and hybrid orangutans. Standardized Animal Care Guidelines have been published or are in development for all of the great apes kept in captivity and may be accessed at http://www.aza.org/animal-care-manuals.2 These Animal Care Manuals (ACMs) provide a compilation of animal care and management knowledge that has been gained from recognized species experts, including Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) Taxon Advisory Groups (TAGs), Species Survival Plan® Programs (SSPs), biologists, veterinarians, nutritionists, reproductive physiologists, behaviorists, and researchers. Captive great ape enclosures must be designed with the animals’ psychological, social, and physical requirements in mind. Husbandry recommendations for great apes are outlined in Table 38-2. Particular attention should be paid to containment requirements for all ages and both sexes and provision of adequate horizontal and vertical spaces to accommodate the complex social interactions of the great apes. A protective barrier between the ape and the human caregiver should enable safe and voluntary interactions between humans and apes. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) has regulations to mandate that any facility that is licensed to sell, exhibit, or do research on primates have a plan in place for environmental enhancement adequate to promote the psychological well-being of nonhuman primates.18 These codes may be found at www.nal.usda.gov/awic/pubs/Legislat/awabrief.shtml. TABLE 38-2 Husbandry Recommendations for Great Apes2 Auxiliary ventilation must be provided when ambient temperature is 85° F (29.5° C) or higher. Institutions that house great apes should have sound nutritional programs, and formulation of ape diets should be made in consultation with nutritionists and veterinarians. Diets need to meet the nutritional and psychological needs of the animals throughout their life stages and should be reviewed on a scheduled basis. All of the great apes are primarily herbivorous and require an exogenous source of vitamin C. Diets may vary considerably among institutions and may consist of commercially available pellets, fruits, vegetables, and browse. The caloric needs of the great apes may be estimated by using the equation: ME (kcal) = 100 × body weight (BW)0.75 in kilograms.28 The nutritional requirements for nonhuman primates are available, but it must be recognized that over 250 primate species exist, so defining species-specific requirements is difficult.28 Nutritional imbalances resulting in health concerns have been seen in captive situations. Vitamin D deficiency has resulted in metabolic bone disease in mother-reared infants that do not have outdoor access and adequate sun exposure. Obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, behavioral issues, and osteoarthritis are also a concern in captive apes fed inappropriate diets.4,5,32,50 Diets made up of primarily high-fiber, low-sugar foods may more closely resemble “wild type” diets and may aid in reducing associated dietary health concerns. The basic components of a medical program for great apes are provided in Table 38-3; these are preshipment health screening and evaluation; quarantine; physical examination, including a comprehensive dental examination; immunoprophylaxis; parasite control; proper nutrition; and monitoring for new medical problems.2,21 A well-rounded preventive medicine plan for great apes must take into consideration the close taxonomic relationship between these animals and humans to have maximum effectiveness.17,27,29,31,48,49,51,52 TABLE 38-3 Recommended Procedures for Scheduled Physical Examinations of Great Apes * Up to institutional clinical risk assessments for use of general anesthesia. † Full panel recommended once, then done as needed based on risk assessment. Full panel includes: simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV); simian foamy virus (SFV); simian T-cell lymphotropic virus (STLV); cytomegalovirus (CMV); herpes simplex virus 1 and 2 (HSV-1, HSV-2); influenza A and B (flu A and flu B); parainfluenza 1, 2, and 3; respiratory syncytial virus (RSV); simian adenovirus (SA-8); measles virus; human varicella zoster (HVZ); Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) +/– hepatitis A and hepatitis B; encephalomyocarditis (EMC). CBC, Complete blood cell count; CT, computed tomography; ECG, electrocardiography; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; IFA, indirect fluorescent antibody; PCR, polymerase chain reaction. Anthropozoonoses are of particular concern and should prompt evaluation of potential ape exposures to human caregivers as well as to the public. Potentially immune-compromised individuals, infants and juveniles, naive populations, and geriatric or chronically ill animals and people are at particular risk. Although the zoonotic disease risks are too many to detail in this chapter, a few are worthy of mention because of their documented effects on great apes. Viruses that cause upper respiratory infections such as colds and influenza may be easily transmitted between humans and apes, and close contact with humans, especially young children (or parents of young children), may increase the likelihood of upper respiratory infections in apes.15,34 Humans with any active upper respiratory infections should not work in close contact with apes or prepare food or enrichment items. Bacterial diseases, especially gastrointestinal (GI) illnesses such as those caused by Salmonella sp., Campylobacter, Yersinia, and Shigella sp. may also be of zoonotic concern and result in clinical illnesses.32,39,40 Devastating losses in wild populations of African great apes from Ebola viruses have also been documented.36 Effective preventive medicine protocols need to take into consideration the use of personal protective equipment (PPE; e.g., N-95 masks, protective clothing, gloves, etc.), and cleaning and hygiene regimes, as well as the health of the humans in close contact with the apes. Prior to transfer from one institution to another, it is important to determine the health status of individual animals. This ensures that the animals are healthy enough to withstand the transfer and will not be carrying novel infectious or parasitic diseases into naïve collections. A thorough health history of the individual animal, as well as a review of disease concerns within the originating collection, is warranted before requesting specific preshipment testing. At a minimum, all great apes should have a complete blood cell count (CBC), blood chemistry, endoparasite testing, fecal bacterial cultures, and testing for tuberculosis (TB) exposure. Additional testing options will depend on the situation but may include total cholesterol levels, thyroid hormone testing, and screening for more infectious viral and bacterial agents. In adult animals, it is recommended that a complete examination of the cardiovascular health of the animal be performed before shipment occurs. Additionally, because of the high incidence of respiratory disease in orangutans, it is strongly recommended that a thorough evaluation of orangutan respiratory health be done prior to transfer.2 Newly acquired animals should go through a quarantine period before being introduced into existing collections. Quarantine periods and examinations may vary greatly among institutions and are dependent on the origin of the animal, evaluation of health and infectious disease status, amount of prearrival screening done, and husbandry adjustments needed. A quarantine period of 30 to 90 days should include one to two physical examinations, consisting of CBC, blood chemistry panels, TB testing, and appropriate infectious disease screening. Parasitic disease risks should be assessed with a minimum of three fecal examinations (floats, centrifugation, sedimentation, or all; direct fecal smears) and bacterial fecal cultures should be done to detect potential pathogens such as Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter sp., enterotoxogenic Escherichia coli and Yersinia spp. If the receiving institution cannot sufficiently quarantine new animals, quarantine may occur at the originating institution as long as the animal is isolated during this time frame and shipped in isolation. The Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) considers this to be an adequate quarantine in these circumstances. If an appropriately designed and physically isolated quarantine facility is not present at either institution, then minimizing infectious disease risks from newly acquired animals may be attempted by preventing physical, aerosol, and fomite transmission of pathogens and establishing strict cleaning and PPE guidelines. All applicable regulations must be followed and zoonotic disease prevention procedures and staff training protocols established to minimize the risk of transferable diseases. Increased attention to enrichment is necessary when apes are housed in isolation during quarantine periods of any length. Decisions regarding frequency of hands on examinations performed under general anesthesia varies between institutions and should be determined by an institutional and individual animal risk review. Great apes are generally too strong and agile to be handled without the use of chemical immobilizing agents; therefore, for any diagnostic or treatment procedure that requires more than minimal interactions done through operant conditioning, general anesthesia is usually required. Consideration of the collections’ historic disease risk analysis, taxonomic recommendations made by species experts, life stage risks (i.e., evaluation of health risks based on age), as well as evaluations of the risks versus the benefits of anesthesia may all factor into the frequency of recommended immobilizations done during an individual animal’s life span. Some limited diagnostic procedures including blood collection, auscultation, cursory dental examinations, cardiac echosonographic evaluations, neonatal examinations, blood pressure measurements, and radiography may be done on nonanesthetized animals through training. Figure 38-4 shows an example of a blood pressure monitoring apparatus, and Figure 38-5 shows it in use with an adult male gorilla. Commercial squeeze cages are available for apes but may have limited usefulness in these large and strong animals. Preventive medicine programs for captive great apes may or may not include a variety of vaccination protocols. Decisions on immunoprophylaxis of great apes are often based on a situational risk analysis taking into consideration geographic disease risks, human interactions, operant conditioning to allow for nonanesthetized access, individual animal disease risk, access to mother-reared infants, and examination frequency. Vaccination of free-living great apes has been proposed as a possible means to mitigate the potentially devastating effects of reverse zoonosis to these vulnerable populations of animals.41,48,51 Factors such as cost, practicality, and wildlife welfare and management must be considered when evaluating the use of commercially available vaccines in wild populations. Recommendations for human vaccination (with the addition of rabies prophylaxis if the apes may potentially interact with wild mammals) may be used as general guidelines when devising vaccination protocols for great apes and, whenever possible, killed vaccines should be used. In addition, consultations with local public health officials, infectious disease experts, and on-line resources for human vaccination schedules, as well as species experts and other zoo and wildlife veterinarians may offer the veterinarian an overview of recommended vaccination protocols being used. The use of vaccinations in great apes is considered “off-label,” and therefore specific brand names cannot be given. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommended immunization schedule is outlined in Table 38-4 and may be used as a reference point from which vaccination protocol discussions may be started. TABLE 38-4 Recommended Human Immunization Schedule* * From the American Academy of Pediatrics, 2012 Immunization schedule: http://aapredbook.aappublications.org/site/resources/IZSchedule.pdf. mo, Month; q10yr, every 10 years; yr, year. Sexual behaviors and hormonal parameters in great apes have been studied and documented for all great ape genera.2,3,7,11,35,43 Reproductive parameters are given in Table 38-5. Assisted reproductive techniques have been tried in apes and have met with variable success. Information on contraception of apes may be found at the AZA Wildlife Contraceptive Center (www.stlzoo.org/contraception). Methods for male contraception include vasectomy, vas ligation (potentially reversible), open-ended vasectomy (potentially reversible), and gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists. Methods of female contraception include intrauterine devices (IUDs), GnRH agonists, progestin contraceptives such as melengestrol acetate (MGA) implants, medroxyprogesterone acetate injections, and levonorgestrel implants, as well as progestin and combination estrogen–progestin oral birth control pills (noncompliance issues have been linked to failures). Hormonal intervention may result in weight gain as in humans; progestins may exacerbate subclinical diabetes, although further studies in apes are needed to clarify whether this also occurs in great apes.24,25,37 TABLE 38-5 Reproductive Parameters in Great Apes * Gestation calculations based on three different methods of calculation: days from last menses; days from last tumescence (if present), days from urinary hormonal changes. † E1C, Urinary estrogen conjugates. Medical problems associated with pregnancy have occurred and may include abortion, placenta previa, endometriosis, pregnancy toxemia, fetal septicemia, retained placenta, dystocia, and congenital defects. Extensive abdominal adhesions are common in great apes and in cases of severe endometriosis and uterine neoplasia, consultation with human oncologic reproductive surgeons may be warranted before attempting surgical removal. Prenatal ultrasonography has been used in nonanesthetized apes to monitor fetal development, and, as in humans, gestational issues may be linked to concurrent health issues such as diabetes, obesity, and hypothyroidism. Figure 38-6 shows gestational ultrasonography performed on a nonanesthetized orangutan for fetal monitoring. Uterine, ovarian, and testicular neoplasia may also affect the great apes, especially older animals. Ideally, all healthy ape infants should be left with their natural dam or placed with a comparable ape surrogate for social rearing if maternal rejection or neglect occurs. Newborn apes may not suckle for the first 12 hours, but they should appear bright eyed, strong, and responsive with a strong grip on their mothers. If neonates show signs of weakness, lethargy, diarrhea, or dull eyes, they may deteriorate rapidly. If neonates show signs of illness, they should be assessed quickly, and usually sedation of the dam is necessary to obtain access to the infant. Neonatal physical examinations should include screening for congenital defects, trauma, neonatal disease, malnutrition, or maternal neglect. The timing of these examinations varies widely among institutions, and decisions need to be based on infant’s current health, maternal–infant bonding, and risk to the infant if darting the mother is needed to separate the pair. The most common illnesses associated with great ape neonates are hypothermia, hypoglycemia, dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, enterocolitis, respiratory disease, urologic disturbances, and sepsis.2 Neonates requiring nursery care or treatment are highly susceptible to hypothermia and need to be kept warm, either in incubators or by being held close to the body, until they may maintain their own body temperature. It is recommended that medically stable infants be returned to their dam or surrogate as soon as possible. If this cannot occur, keeping them within auditory, visual, olfactory, and supervised tactile reach of their dam or group is beneficial. Serious, even fatal, respiratory illness may occur in hand-reared infants with prolonged close human contact, so the use of proper PPE (face masks, gloves, etc.) and health of the human caregivers cannot be overemphasized. Most commercially available human infant formulas may be used for feeding great ape neonates. Lactose intolerance and iron sensitivity may occur, so selection of formulas that are soy based and low in iron may be prudent. With the increasing life expectancies seen in captive great apes, challenges in geriatric care and management should be discussed as part of the preventive medicine program. Maintaining a schedule of routine physical examinations and possibly even increasing the frequency of these examinations, balanced with potentially increased anesthetic risks, may be challenging. Common age-related health issues in geriatric apes include renal disease, reproductive disorders, abdominal abscesses, cardiovascular disease, dental issues, vision degeneration, and osteoarthritis.2,30,32,39,40,50 Specific medical, nutritional, exhibit design, and enrichment protocols may need to be modified for these geriatric challenges. Particular attention should be paid to the prevalence of osteoarthritis when positioning anesthetized geriatric animals, and limb and joint support should be of paramount concern to reduce painful and sometimes long-lasting side effects in recovery. Figure 38-7 shows one method for supporting the limbs of a geriatric, anesthetized gorilla during a procedure. Thorough physical examinations on great apes require the use of general anesthesia induced via chemical immobilizing agents. No immobilization is completely risk free, so institutional and individual veterinarians must weigh the risk of anesthesia with the benefit of improved diagnostic abilities and thorough physical examinations. A number of commercially available anesthetics may be used alone or in combination to induce and maintain general anesthesia in great apes, and these may be viewed in Table 38-6.1,44 All apes should be fasted for a minimum of 12 to 24 hours before anesthesia is induced, and water should be withheld for at least 12 hours. If an oral preanesthetic needs to be used, care must be taken to avoid delivering the drug in large volumes of food or liquids, as complications from regurgitation and aspiration may occur during induction. Drug delivery is usually by the intramuscular route, and training the apes for hand injections is preferred. Hand injections of anesthetics via operant conditioning may avoid the stress of darting animals with remote drug delivery systems and will often lead to smoother induction, better planes of anesthesia, lower anesthetic doses, and safer drug deliveries. If this is not an option, remote darting may be used. The use of pole syringes in completely awake apes is not usually successful because of their agility and strength. TABLE 38-6 Chemical Restraint and Anesthetic Induction Agents Used for Great Apes21,44

Great Apes

Biology

Genus

Species

Subspecies

Common Name

Weight (adult in kg)

IUCN Status

Pongo

pygmaeus

ssp. morio

Northeast Bornean Orangutan

50–100 kg (M)

30–50 kg (F)

Endangered

ssp. pygmaeus

Northwest Bornean Orangutan

ssp. wurmbii

Central Bornean orangutan

Pongo

abelii

Sumatran orangutan

80–90 kg (M)

33–45 kg (F)

Critically endangered

Gorilla

beringei

ssp. beringei

Mountain gorillas

180–220 kg (M)

70–90 kg (F)

Endangered

ssp. grauri

Eastern Lowland or Grauer’s gorilla

160–250 kg (M)

70–120 kg (F)

Gorilla

gorilla

ssp. gorilla

Western lowland gorillas

140–270 kg (M)

70–90 kg (F)

Critically endangered

ssp. diehli

Cross River gorilla

180 kg (M)

Pan

troglodytes

ssp. ellioti

Nigerian-Cameroon chimpanzee

40–70 kg (M)

32–47 kg (F)

Endangered

ssp. schweinfurthii

Eastern chimpanzee

45–90 kg (M)

40–80 kg (F)

ssp. troglodytes

Central chimpanzee

45–90 kg (M)

40–80 kg (F)

ssp. verus

West African chimpanzee

45–90 kg (M)

40–80 kg (F)

Pan

paniscus

Bonobo

25–45 kg (M)

25–40 kg (F)

Endangered

Unique Anatomy

Captive Management

Special Housing Requirements

Recommendations

Orangutans

Gorillas

Chimpanzees

Bonobos

Temperature

64° F (18° C) to 84° F (28° C)

65° F–85° F

60° F–85° F

64° F (18° C) to 72° F (22° C)

Humidity

30%–70%

30%–70%

30%–70%

50%–60%

Ventilation

10–15 air changes per hour (hr)

10–15 air changes/hr

10–15 air changes/hr

10–15 air changes/hr

Feeding

Preventive Medicine

Procedure

Frequency

Notes

Physical examination

1–2 times in quarantine, every 1–3 years*

Partial visual examinations may be done through the use of operant conditioning but general anesthesia is needed for a complete physical examination

Dental examination

Every 1–3 years

Complete examination requires general anesthesia

Accurate weights

Monthly

Scales should be designed into holding or exhibit areas

Blood collection

Every 1–3 years, some animals may be trained for voluntary blood draws more frequently

Routine on all: CBC, chemistry panel, viral serology†, serum banking (all ages)

Additional tests: thyroid panel, cholesterol, lipid panel, cardiac disease markers

Rectal culture

Every 1–3 years

For Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, Yersinia, pathogenic E. coli strains

Fecal examination

Every 3–6 months

Includes direct and concentrating techniques (flotation, centrifugation, sedimentation)

Additional diagnostics targeting parasites of concern may include Giardia and Cryptosporidium screening (e.g., IFA, ELISA, PCR), and Baermann technique for identification of select nematode larvae

Mycobacterial testing

Every 1–3 years

Intradermal skin test, lavage (gastric, tracheal, bronchial)

ELISA (e.g., ChemBio)

PCR testing, γ-interferon testing (e.g., Primagam).

Mycobacterial testing results from orangutans are challenging to interpret and many tests have not been validated

Imaging

Every 1–3 years

Radiography (thoracic, abdominal, dental) recommended for all ages

+/– Abdominal ultrasound for adults

-Echocardiography, blood pressure measurements, ECG; once as juveniles, then every 1–3 years once adults

CT imaging of sinuses, air sacs, and thorax recommended to screen for respiratory infections in orangutans when feasible

Vaccinations

Varied frequency

See table 38-4

Identification

Once

Permanent identification for individuals may include natural markings, photographs of facial characteristics, tattoo, transponder chips

Health Screening and Evaluation

Preshipment Evaluations

Quarantine

Physical Examinations

Immunoprophylaxis

Immunization

Abbreviation

Dosing Schedule

Hepatitis B

Hepatitis B

birth; 1 mo; 6–18 mo

Rotavirus

RV

2 mo; 4 mo

Diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis

DTaP

2 mo; 4 mo; 6 mo; 15–18 mo; 11–12 yr; q10yr

Haemophilus influenzae type b

Hib

2 mo; 4 mo; 12–15 mo

Pneumococcal

PCV

2 mo; 4 mo; 6 mo; 12–15 mo

Inactivated poliovirus

IPV

2 mo; 4 mo; 6-18 mo; 4–6 yr

Influenza

—

Annually

Measles, mumps, rubella

MMR

12–15 mo; 4–6 yr

Varicella

Varicella

12–15 mo; 4–6 yr

Hepatitis A

HepA

12–24 mo; 2nd dose 6–18 mo later

Meningococcal

—

11–12 yr; 16 yr

Human papillomavirus

HPV

3-dose series, beginning at age 9

Reproduction

Parameter

Gorillas

Chimpanzees

Bonobos

Orangutans

Puberty, age (years)

6–7.5 female (F)

10–15 male (M)

6–10 (F)

7–13 (M)

6–11 (F)

13 (M)

7–10 (F)

7–9 (5–17) (M)

Youngest age to breed (years)

8–10 (M)

6–9 (F)

5–10 (F)

6–13 (M)

10.1 ( 8.3–14.9 y) (F)

7y (M)

5–7 (F)

Estrous cycle Length (days)

33 (21–49)

36 (28–53)

31–51

28 (23–33)

Menses (days)

1

2–7

3–4

1–4

Receptivity detection (days)

2 (1–4)

6 (may be receptive throughout cycle)

May be receptive throughout cycle

2(1–4)

Uterus

Simplex

Simplex

Simplex

Simplex

Gestation (days)*

255 (237–285)

227 + 12

233–247

245 ± 12

Pregnancy determination

Commercially available urinary human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) tests

Commercially available urinary hCG tests

10–20× increase in urinary E1C †(10–30 days postestrogen peak); commercially available urinary hCG tests

Commercially available urinary hCG tests (mixed results)

Placentation

Hemochorial, villous, discoid

Hemochorial, villous, discoid

Hemochorial, villous, discoid

Hemochorial, villous, discoid

Luteal phase (days)

11.2 ± 0.8

15 (13–18)

11–15

13.5

Follicular phase (days)

18.14 ± 1.7

20 (15–25)

17–40

12 (11–15)

Reproductive Disorders

Neonatal Care

Geriatric Care

Anesthesia

Generic Name

Orangutan

Chimpanzee

Gorilla

Reversal Agent/Dose (mg/kg)

Comments

INDUCTION AGENTS

Ketamine hydrochloride

6–10

5–20

6–10

None

Rapid induction; minimal cardiovascular (CV) and respiratory changes; not reversible; short duration of action

Ketamine/Xylazine

5–7 (K) / 1–1.4 (X)

5–10 (K) / 1 (X)

Yohimbine 0.125–0.25 for X

Rapid induction; CV stable; longer anesthetic times

Ketamine/Medetomidine

2–7 (K) / 0.03–0.04 (M)

2–5 (K) / 0.02–0.05 (M)

2–5 (K) / 0.02–0.05 (M)

Atipamazole 0.1–0.5 (M)

Spontaneous arousal; potential for CV side effects, reversible

Ketamine/midazolam

1–2 (K) / 0.03 (M)

9 (K) / 0.05 (M)

Flumazenil 0.02–0.1, IV for midazolam only

Shorter duration of effect than telazol; drug volume may be an issue

Tiletamine/Zolazepam (Telazol)

2–6.9

2–6

2–6

Flumazenil 0.02–0.1, IV, for zolazepam only

Smooth inductions; may have prolonged recoveries

Telazol/Medetomidine

0.8–2.3 (T) / 0.02–0.06 (M)

1.25 (T) / 0.03–0.04 (M)

Atipamazole 0.1–0.25 for medetomidine

Monitor blood pressure and respirations

Provide oxygen support

TRANQUILIZERS AND ANALGESICS

Diazepam

0.5–1.0 PO/IM/IV

0.2, PO

Flumazenil 0.02–0.1, IV

May reduce anxiety; may be used in combination with other drugs for inductions

Midazolam

0.05–0.15 IM/IV/PO

Flumazenil 0.02–0.1, IV

May reduce anxiety; may be used in combination with other drugs for inductions

Butorphenol

0.1–0.2 IM/IV

Naloxone 0.02, IM/IV

May be used in combination with other drugs for inductions

Buprenorphine

0.01–0.02 IM/IV

Naloxone 0.02, IM/IV

May be used in combination with other drugs for inductions

May produce respiratory depression

ANESTHETIC MAINTENANCE

Isoflurane

or sevoflurane

0.5–2.5% + or to effect via endotracheal

tube

same

same

same

May see dose-dependent hypotension

Propofol

To effect:

25–100 µg/kg/min, IV, OR 50 mg/kg TOTAL DOSE

Monitor blood pressure and respirations

May be used for unexpected arousals![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Great Apes

Chapter 38