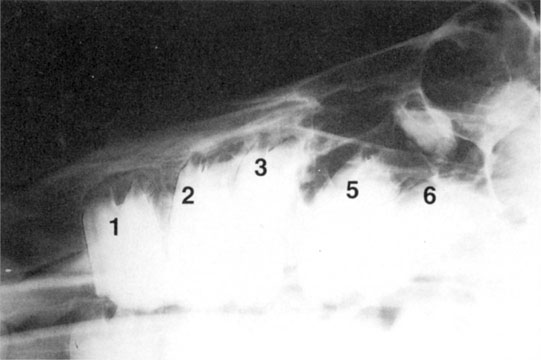

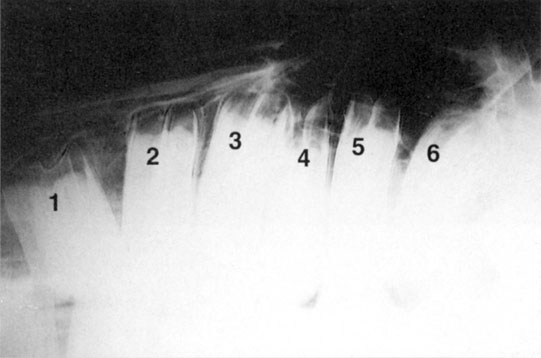

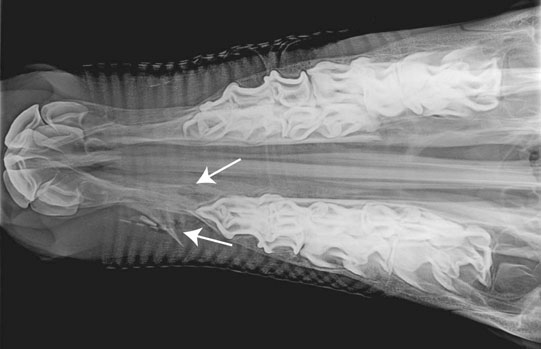

• Treatment needs to be directed at two main areas, correction of the abnormality and treatment of secondary problems such as pneumonia. • Treatment of the defect involves one of a variety of surgical techniques. Dehiscence of the surgical site is a common problem. In severely compromised foals, surgery may need to be delayed while secondary problems (pneumonia, sepsis) are addressed. In these situations, feeding via a nasogastric tube or parenteral nutrition is required. • The prognosis is better in foals with defects only involving the soft palate. • Diagnosis through oral examination. • In many cases, these conditions are more of a cosmetic defect than a true medical problem. The treatment approach is dependent on the severity of the lesion and the age. • Use of bite plates and surgical correction have been described for severe cases. Many affected horses will require more frequent dental care. Defects of the teeth relating either to genesis or eruption are relatively common. • Oral examination may be diagnostic for the majority of cases of missing or malerupted teeth. • Radiographs may be required to differentiate supernumary teeth from persistent temporary dentition. A retained deciduous incisor has a more mature root and a shorter reserve crown than those of the adjacent permanent incisors. • Radiographic examination and comparison with the normal arcade anatomy in cases of maleruptions show a variety of deformities ranging from complete absence of the tooth to an obvious tooth growing in an abnormal direction or position. Sometimes however, definite dental structure cannot be identified in a mass of abnormal tissue. • Radiographs can confirm the presence of an aberrant tooth-like structure, which is either firmly attached to the cranium or loosely enclosed in a cystic structure and may in either case be surrounded by a collar of bone forming an apparent alveolus. A contrast fistulogram can be used to delineate the mass and any draining tracts. • Surgical excision is required but may be difficult in some cases where the ectopic teeth are firmly attached. Prognosis following removal is good. • Although the apparent deformity of the mandibular bone may be obvious, radiographs of the area will demonstrate the presence, in young horses, of a normal dental sac, without any evidence of periapical inflammation or infection. • Usually the extent of the defect improves somewhat with age, but persistence of some thickening and deformity are to be expected. Such swellings are totally benign and, in spite of apparently severe cosmetic changes, they are of little or no clinical significance and are in any case untreatable. • Usually obvious but radiographs are often required to determine the extent of the fracture and relationship to adjoining structures. • Treatment is normally surgical; the method chosen is determined by the type of fracture involved. Antibiotic treatment is usually required as the mouth has a high bacterial load and there is usually contamination of the fracture site. In some cases of maxillary fractures secondary infections of the sinuses may occur and require separate treatment. Dental disease is grouped into four basic types: All of these are interrelated, and horses with one type will also have, to varying degrees, the other types of disease. • Wave mouth. Localized differences in the density of the occlusal surfaces of the molar teeth may also have marked effects upon the occlusal efficiency and the development of abnormal wear patterns. Alternate hard and soft areas in the structure of the cheek teeth or, more commonly, stereotyped chewing behavior, may result in the development of wave mouth in which either a series of waves develops on the occlusal surface or individual teeth wear faster or slower than their neighbors giving a much coarser irregularity of occlusal surfaces. • Step mouth. In other cases, there may be one (or more) tooth which, often for inexplicable reasons, wears excessively. This results in gross variations in the height of the teeth (step mouth) and necessarily limits the occlusal efficiency. The full extent of the condition may only be apparent from lateral radiographs when gross variations in height and pyramid deformities of the crowns of the molar teeth may be present. • Shear/scissor mouth (see p. 3). While the loss of lateral grinding movement of the molars, for any reason, will initially induce sharp buccal margins on the upper teeth, this may progress into a severe and debilitating parvinathism (shear/scissor mouth), in which lateral movement, which is essential for normal chewing, is prevented. These unfortunate horses are often noted to have an abnormally narrow lower jaw but, while under these circumstances it is regarded as a developmental deformity, the same dental deformity may develop as a consequence of a sensitive molar tooth (or teeth) in the opposite arcade or from pain associated with the temporomandibular joints. This results in the upper molars becoming bevelled from the inside outwards with the lower molars worn in the opposite fashion. This deformity prevents further lateral movement of the teeth and seriously interferes with mastication. Under these circumstances extensive overgrowth or bizarre dental deformities may be encountered. This may itself induce secondary temporomandibular arthropathy as the animal attempts to chew with the sides of the molar teeth. It is, in most cases, impossible to identify whether the occlusal problem arose first and caused secondary joint degeneration, or whether the occlusal deformity is the result of abnormal jaw movement created by joint inflammation and degeneration. It represents one of the most serious deformities of the horse’s mouth and carries a poor prognosis. • Sand mouth. In areas where horses have, of necessity, to eat and chew large amounts of sharp sand or other abrasive substances the occlusal surface of the cheek teeth may become completely smooth and therefore ineffective as grinders of food. Failure to masticate efficiently results initially in difficulty with swallowing and slow eating. Weight loss, as a result of ineffective digestion, is commonly present. Under similar circumstances, because these horses are usually grazing very short pasture or having to find food in soil or sand the incisors may become severely worn down. • Overgrown cheek teeth. Overgrown cheek teeth may arise from the absence of the opposite occlusal tooth. Such defects may follow either from normal old-age shedding, or from failure of normal eruption or, more often, from surgical extraction of one or more of the cheek teeth. Molar teeth with no occlusal pressure are likely to grow faster than normal teeth and in addition have no occlusal abrasion. The resultant loss of normal control of dental growth creates abnormal wear patterns which are usually visible as gross overgrowth. Pyramidal peaks on the tooth opposite the gap are common where the gap created by a missing cheek tooth is narrowed by angulation of the adjacent teeth but leaving a relatively small area of non-occlusion. • Excessive incisor wear. While severe incisor wear is sometimes encountered where grazing is short and large amounts of sand or other abrasive substances are ingested, the wear pattern of the incisors, in particular, may be influenced by behavioral factors. Crib-biting is a common vice (neurosis) developed by horses showing a characteristic wear pattern on the rostral margin of the upper incisor teeth which is variable in extent according to the severity and duration of the vice, and to some extent upon the structural character of the teeth. The earliest indications of the vice may be gained from close examination of the rostral margin of the upper central incisors where a worn edge will be detected. The persistence and severity of the effort involved in cribbing is often enough, even in young horses, to cause severe wear of the central incisors, often down to gingival level.

Gastrointestinal system

Part 1: The mouth

Developmental disorders

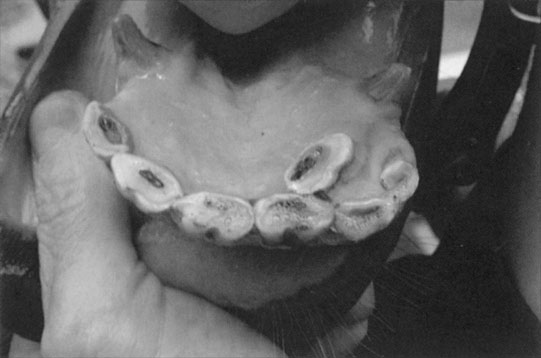

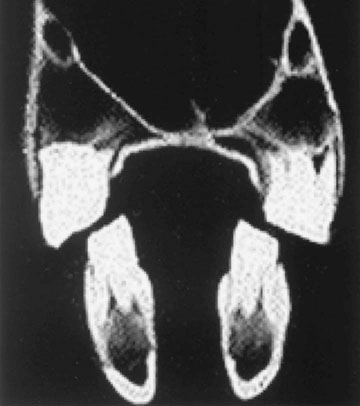

Cleft palate (Figs. 1.1–1.3)

Differential diagnosis: Nasal/oral discharge of milk and/or dysphagia may also be seen with:

Treatment

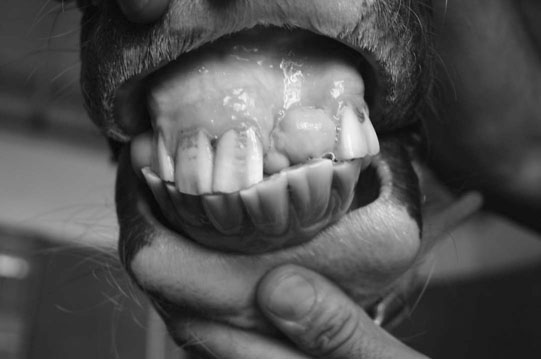

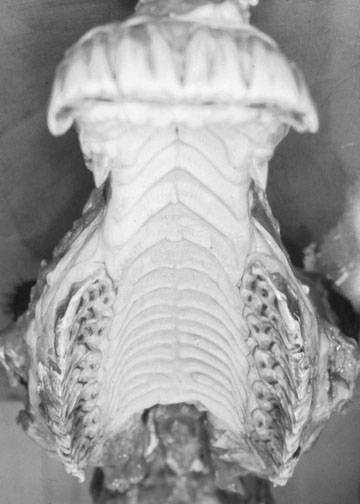

Parrot mouth (brachygnathia) (Figs. 1.5–1.7)

Sow mouth (prognathia) (Figs. 1.8 & 1.9)

Diagnosis and treatment of parrot mouth/sow mouth

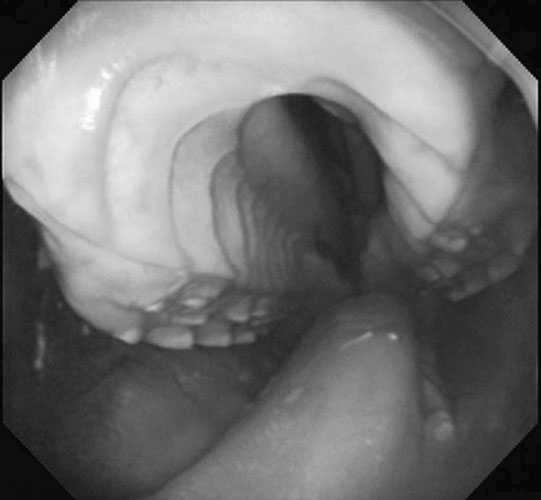

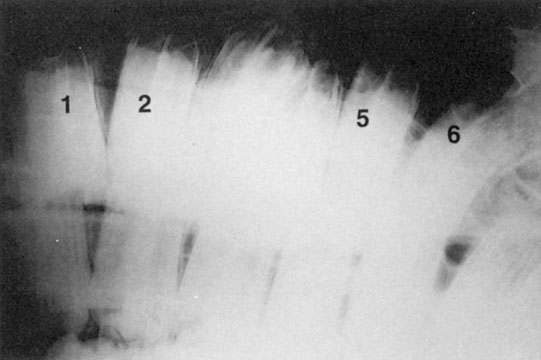

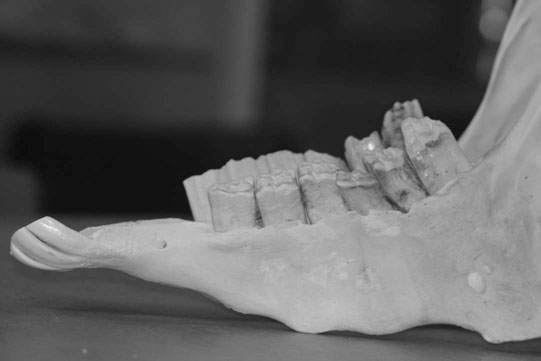

Missing and malerupted teeth (Figs. 1.10–1.18)

Supernumerary teeth

Diagnosis of missing/malerupted teeth

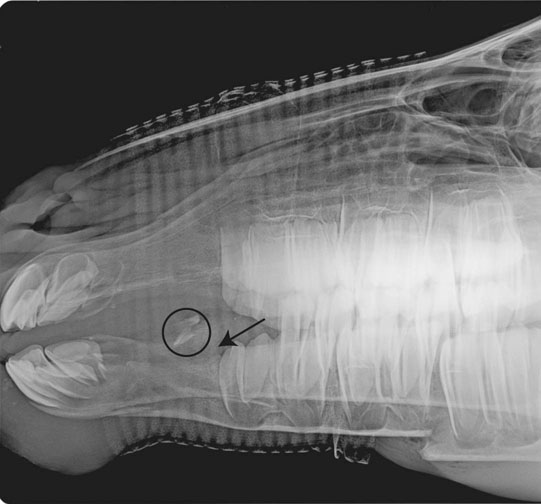

Dentigerous cysts (Figs. 1.20 & 1.21)

Differential diagnosis:

Diagnosis and treatment

Non-infectious disorders

Dental tartar (Figs. 1.22 & 1.23)

Ossifying alveolar periostitis (Fig. 1.24)

Differential diagnosis:

Diagnosis and treatment

Fractures of the maxilla and mandible (Figs. 1.26–1.30)

Diagnosis and treatment

Dental disease

Abnormal wear patterns (Figs. 1.31–1.38)

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree