CHAPTER 18 Gastrointestinal Protozoal Infections

COCCIDIANS

CRYPTOSPORIDIUM SPP.

Etiology

In the past, most mammalian infections with Cryptosporidium spp. were attributed to Cryptosporidium parvum. However, recent genetic studies showed that most isolates from cats are C. felis.1 In cats, sporulated oocysts (4 µm × 6 µm) are passed in the feces after completion of an enteric life cycle.

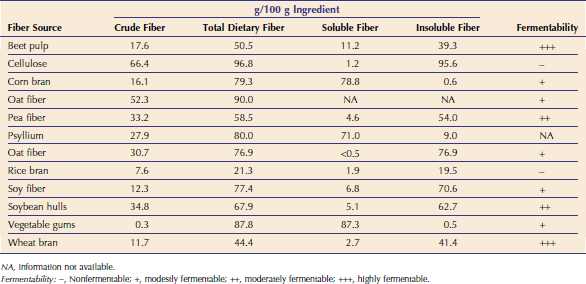

Epidemiology

Cryptosporidium spp.–infected cats have been documented worldwide (Table 18-1). However, the prevalence of C. felis varies based on the study population and on the diagnostic test used.2–17 For example, in one study of 180 cats with diarrhea in the United States, the prevalence rates based on an immunofluorescent antibody assay and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were 3 per cent and 29.4 per cent, respectively.13 Therefore, while the true prevalence of C. felis is unknown, it is generally between 3 per cent and 20 per cent in cats with diarrhea. Also, in most of the studies, the prevalence tends to be higher in young cats and in shelter cats.

Pathogenesis

Little information is available concerning the pathogenesis of C. felis in cats. Thus, most information is extrapolated from what is known in human beings and mice after infection with C. parvum. Cryptosporidium spp. oocysts are sporulated when passed in feces. After excystation from oocysts, Cryptosporidium sporozoites attach to the intestinal epithelium between the cell membrane and the cell cytoplasm; this location may partially explain their resistance to chemotherapy.18 The initial host-parasite interactions are complex and involve multiple parasite ligands and host receptors.18 The intestinal epithelial cells serve as a physical barrier and produce a variety of cytokines and chemokines in response to the pathogen. C. parvum infection can induce mucosal infiltration with neutrophils, macrophages, and lymphocytes in the lamina propria underlying the epithelial cells, as well as intraepithelial infiltration with neutrophils and T lymphocytes. Proinflammatory cytokines are up-regulated during C. parvum infection.18 Concurrently, antiinflammatory cytokines are produced and play a protective role in limiting the epithelial damage due to the infection.18 Cellular immunity mediated by CD4+ and CD8+ α/β T cells is an important component for the resolution of C. parvum infection. Interferon-γ also appears to play an important role in innate immunity and in the cell-mediated response against C. parvum.18 In otherwise healthy specific-pathogen–free cats, inoculation with C. parvum oocysts resulted in chronic infection, but minimal clinical signs of disease, even after the administration of glucocorticoids, suggesting that these organisms were minimally pathogenic in these healthy cats.19

Clinical Signs

Cats with C. felis infections can be infected clinically or subclinically, but most infections are subclinical. When clinical signs occur, cryptosporidiosis usually is characterized by small bowel diarrhea, anorexia, and weight loss. Most cats with C. felis infection and diarrhea have concurrent immunosuppression, preexisting disease in the intestinal tract, or coinfection with other infectious or noninfectious causes.20–22 For example, coinfection with other protozoans, like Giardia spp. and Tritrichomonas foetus, may aggravate clinical signs of cryptosporidiosis in cats.23–25 Noninfectious diseases associated with cryptosporidiosis in cats are lymphoma and inflammatory bowel disease.20,26,27 Cats infected with Cryptosporidium spp. also can serve as subclinically infected carriers. The administration of glucocorticoids to some chronically infected, oocyst-negative cats, may induce repeated oocyst shedding.19

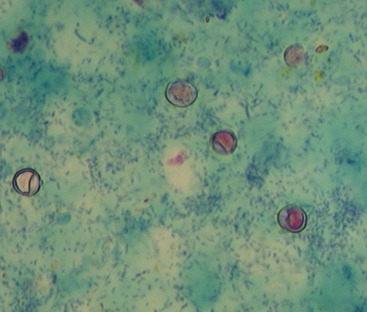

Diagnosis

C. felis oocysts are very small (4 µm × 6 µm) and are shed in low numbers by cats. Therefore results of fecal flotation generally are negative. Staining a thin fecal smear with modified Ziehl-Neelsen acid-fast stain (MZN) can be performed as an in-clinic test (Figure 18-1). A monoclonal antibody–based immunofluorescent antibody (IFA) assay (Merifluor Cryptosporidium/Giardia, Meridian Diagnostics, Cincinnati, OH) designed to detect C. parvum oocysts in human feces has been used in many feline studies and appears to detect C. felis oocysts. This assay has the advantage of detecting Giardia spp. cysts concurrently and thus can be used to identify parasites both by fluorescence and by morphology. However, this procedure requires a fluorescent microscope, and samples therefore must be sent to a reference laboratory. A recent study reported that IFA had a lower sensitivity than the MZN technique when a single fecal sample was tested.28 The sensitivity of IFA and MZN were equal when two to four fecal samples were tested.28

Multiple commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) designed to detect C. parvum antigen in human feces have been assessed for use with feline feces with variable results.28,29 Our laboratory recently evaluated two lateral flow devices for the detection of C. parvum in human feces and found them to be inadequate for detection of Cryptosporidium spp. in feline feces.29 This may relate to antigenic differences between C. felis and C. parvum. In another study, the ProSpecT Microplate Assay (Alexon Biomedical, Sunnyvale, CA) showed the highest sensitivity (71.4 per cent) and specificity (96.7 per cent) of a variety of commercial assays for the detection of Cryptosporidium when compared to IFA.30

Cryptosporidium spp. DNA can be amplified from feces by PCR testing, which is now commercially available at many diagnostic laboratories in the United States. The technique can be more sensitive than IFA.2,19 However, currently there is no standardization between laboratories, and the level of quality control may vary widely between laboratories. The results of PCR also can be used for genotyping to determine whether the Cryptosporidium spp. detected is C. parvum, C. felis, or another Cryptosporidium species (Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO; http://www.dlab.colostate.edu). At this time, PCR is only recommended for assessment of cats with diarrhea because the clinical and zoonotic impact of oocyst-negative, but PCR-positive, healthy cats is unknown.

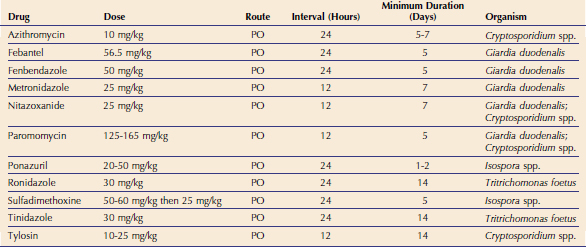

Treatment

It is impossible to determine whether Cryptosporidium spp. is causing diarrhea in a specific patient. However, when a cat with diarrhea is shown to be Cryptosporidium spp.–positive and there is no other obvious cause for the diarrhea, treatment may be indicated. More than 100 compounds have been evaluated for the treatment of cryptosporidiosis in human beings, cattle, and mice, and none control clinical signs of disease consistently or eliminate infection. There are few published reports of treated cryptosporidiosis in cats. Therefore the protocols described here can only be considered anecdotal (Table 18-2).

In one case report, administration of clindamycin hydrochloride to a cat with chronic cryptosporidiosis and lymphocytic duodenitis failed to resolve diarrhea or stop oocyst shedding.20 However, after initiating tylosin therapy, the stool character normalized within 7 days and feces were negative for Cryptosporidium spp. oocysts over a period of 6 months. Also, the inflammatory changes in the bowel resolved, and the cat was clinically normal over a 2-year period, which suggested a therapeutic response. We have treated other cats with presumed cryptosporidiosis with tylosin, and diarrhea has resolved in about 50 per cent of cases (Scorza and Lappin, unpublished observations, 2008). However, these observations are uncontrolled, and the signs in the affected cats may have resolved spontaneously without any treatment. However, it is likely that the antiinflammatory or antibacterial effects of tylosin play a role in the clinical response to the drug. Tylosin is not tolerated well by most cats because of its unpleasant taste and thus needs to be administered in capsules to many feline patients.

Recently, azithromycin has been shown to be effective for the management of cryptosporidiosis in some infected calves.31 Azithromycin is well tolerated by cats and has been administered at 10 mg/kg PO q24h for a minimum of 10 days for the treatment of cryptosporidiosis with a variable response.

Paromomycin, an aminoglycoside for oral administration, was effective in clearing Cryptosporidium oocysts from the feces of a naturally infected cat with persistent diarrhea and in a group of experimentally inoculated cats.32,33 However, the diagnostic tests used in the follow-up period in both studies may not have been adequately sensitive to detect cats who may have been in a carrier state. It is important to note that this drug should never be administered to cats with bloody diarrhea because it could be absorbed systemically. In one study of cats with Tritrichomonas infection treated with paromomycin, four out of 32 cats developed acute renal failure, and three of those four cats also became deaf.34

To date, nitazoxanide is the only drug approved by the U. S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of diarrhea caused by Cryptosporidium in children and in adult human beings.35 We are currently evaluating nitazoxanide for the treatment of a number of small-animal parasites. Some cats with Cryptosporidium spp. or Giardia spp. infections have shown resolution of diarrhea after the administration of nitazoxanide at a dosage of 25 mg/kg PO q12h for at least 5 days. However, the drug is a gastrointestinal irritant and commonly causes vomiting.

The optimal duration of therapy for feline cryptosporidiosis is unknown, and some cats treated with the protocols described in Table 18-2 may improve but may not resolve by the end of the suggested treatment period. In these cats, continued treatment may be indicated because a longer duration of therapy is sometimes needed to resolve the diarrhea. Cats with Cryptosporidium spp. and Giardia spp. coinfections seem to be more difficult to treat than cats infected with either organism alone. Some coinfected cats have required administration of paromomycin or nitazoxanide daily for more than 21 days to eliminate diarrhea.

Zoonotic Transmission

Most cats are infected with the cat-specific genotype C. felis.1,14,36,37 Although C. felis DNA has been amplified from the feces of some human beings, molecular and epidemiological data suggest that the risk of zoonotic transmission of Cryptosporidium from companion animals to people is low.38,39 However, care should be taken when handling the feces of cats with Cryptosporidium spp. infection and diarrhea.

ISOSPORA (CYSTOISOSPORA) SPP.

Pathogenesis

Infection occurs either through the ingestion of infective oocysts from the environment or when a cat eats a prey animal infected with the parasite. Oocysts are passed unsporulated in feces, and after exposure to warm temperature (20° C to 37° C) and humidity, sporulation occurs and two sporocysts are formed (Figure 18-2). Within each sporocyst are four infective sporozoites. After ingestion, sporozoites excyst in the intestinal lumen and undergo a series of asexual replications, followed by sexual replication, which leads to the formation of unsporulated oocysts that are shed in feces. Some sporozoites penetrate the intestinal wall and form unicellular cysts in the mesenteric lymph nodes or other extraintestinal tissues. These cysts may serve as a source of reinfection. Vomiting and diarrhea can occur and result from intestinal congestion, erosion of enterocytes, and atrophy of villi. These clinical signs occur mainly in kittens and young cats during the enteroepithelial cycle. I. felis generally is considered more pathogenic than I. rivolta.

Treatment

It is questionable whether Isospora spp. infections cause chronic diarrhea in adult cats. If oocysts are found in feline patients with chronic diarrhea, the presence of another underlying disease should be considered. Sulfonamide-containing drugs have been used classically for treatment if clinical illness from Isospora spp. infection is suspected. However, these drugs are coccidiostatic, may be poorly tolerated by kittens, and have to be prescribed for long periods of time to be effective (see Table 18-2). Toltrazuril has been shown to be effective, but is currently not available in the United States.40 Although no literature has been published on it, the related drug ponazuril is available for large animals and has been used safely for the treatment of Isospora spp. infection in kittens. Ponazuril (Marquis Paste, Bayer Animal Health) can be diluted at 1 g of paste to 3 mL of water, which gives a solution of 37.5 mg/mL. The drug is thought to be stable for several weeks after dilution. Ponazuril can be administered at 20 mg/kg PO q24h for 2 days, or at 50 mg/kg PO as a single dose. Both regimens appear to be safe and effective. Consideration should be given to treating cats who can be considered in-contact to the infected cat to attempt to prevent recurrent infection. Treatment of subclinically infected cats may lessen oocyst shedding and resultant environmental contamination. However, infection is not always cleared. In addition, the presence of a low-level infection can lead to premunition.

FLAGELLATES

GIARDIA SPP.

Etiology

Giardia duodenalis is a protozoan parasite with worldwide distribution that infects a variety of mammals. The G. duodenalis isolates from human beings and animals are indistinguishable morphologically. Molecular genetic studies have demonstrated that G. duodenalis is a species complex comprising seven assemblages (A to G). Some of the assemblages have been detected in animals and human beings, but some are host-specific. Cats can harbor the cat-specific assemblage F (Tables 18-3 and 18-4) and also occasionally the assemblages A and B, which represent the genotypes that have mainly been detected in human beings.41–50 The organism exists in two stages, the motile trophozoite and the environmentally resistant cyst.

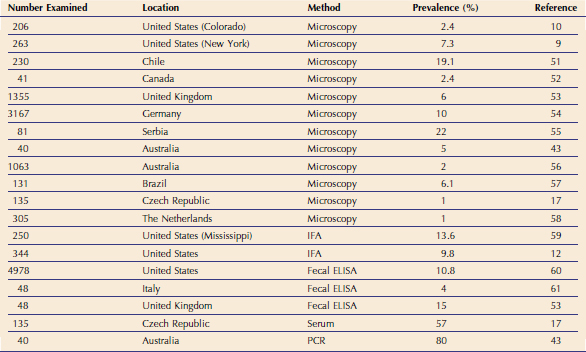

Epidemiology

Giardia spp. have been detected in feces from cats around the world (Tables 18-4 and 18-5). However, the prevalence of Giardia spp. varies, based on the study population and on the diagnostic test used.* Thus, although the true prevalence of Giardia spp. infections in cats is unknown, it is generally believed to be between 1 per cent and 20 per cent in cats with diarrhea. Young, immunodeficient, and group-housed cats are thought to be more susceptible to infection and clinical disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree