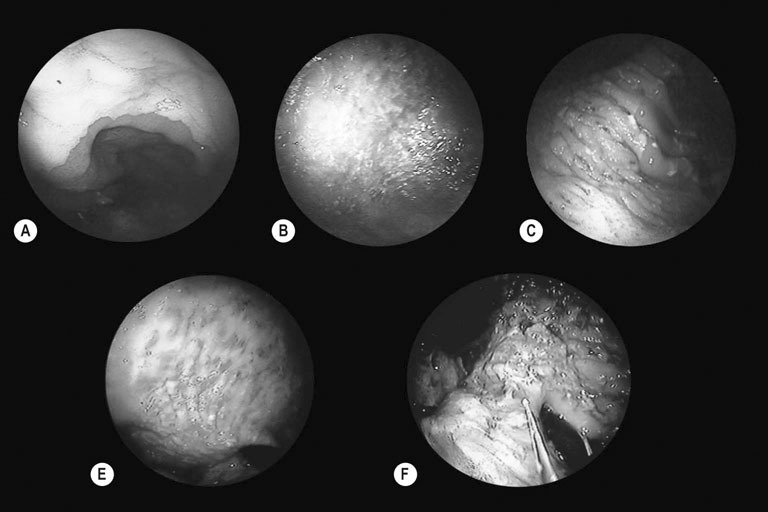

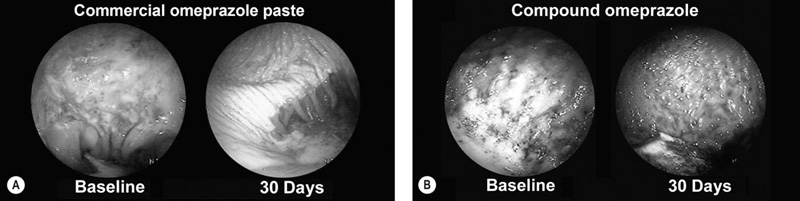

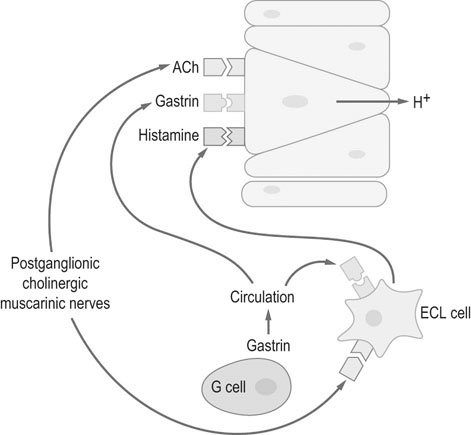

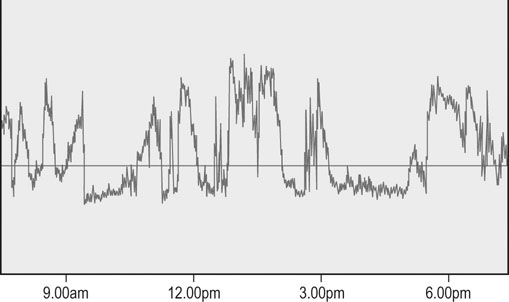

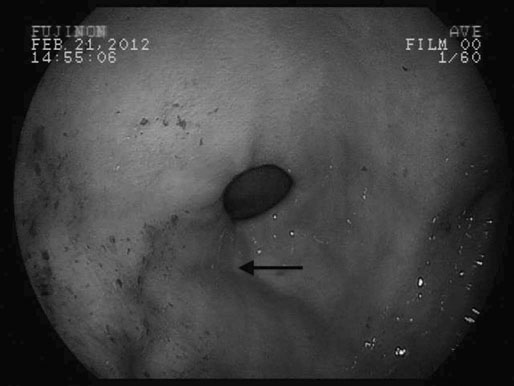

Moderate exercise and an active lifestyle have potential benefits to the gastrointestinal tract. Several studies in humans have shown an inverse relation between physical activity and the risk of gastrointestinal disease such as colon cancer, constipation, inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel disease.1 However, strenuous exercise in human athletes has been associated with development of gastrointestinal disturbances, with symptoms reported to occur in up to 70% of endurance athletes during exercise.2 Gastrointestinal bleeding, abdominal cramping, nausea and diarrhea have been described in marathon runners.3,4 The gastrointestinal symptoms have been attributed to motility disorders, mechanical factors, altered secretion of neuroendocrine hormones and gastrointestinal ischemia.5 During exercise, splanchnic blood flow is redistributed to the working muscles and skin, at the expense of bowel perfusion. During high-intensity exercise, splanchnic blood flow may be reduced by up to 70%, and it has been estimated that gastrointestinal ischemia might be induced by a 50% reduction of splanchnic blood flow.5 In addition, it has been reported that the use of some non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may predispose to gastrointestinal problems related to marathon running.4 Limited information exists regarding changes in blood distribution, motility, secretion and absorption through the gastrointestinal tract in horses during exercise. However, a study in ponies exercised on a treadmill, at an intensity of 75% of heart rate maximum, showed a significant reduction in blood flow (between 40 and 50%) to the large colon and cecum.6 Therefore it is possible that some of the gastrointestinal clinical signs observed in horses during or after exercise may be due to the same proposed mechanism for human athletes. • The prevalence of gastric ulceration is high in athletic horses. Although racehorses in active training have the highest prevalence and severity of gastric ulceration, horses in other athletic disciplines are also commonly affected. • The cause of gastric ulceration in horses is multifactorial. • The diagnosis of gastric ulceration in horses is based on history, presence of clinical signs and confirmed by gastroscopy or response to therapy. • The recommended treatments include the use of agents to decrease stomach acidity and management modifications. It has been estimated that approximately 2% of the human adult population suffers from gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Signs and symptoms of GERD include acid reflux and heartburn. Up to 36% of healthy Americans suffer from heartburn at least once a month. GERD is a multifactorial disease that occurs when stomach acid and/or bile fluid flows back into the esophagus. With the availability of three-meter-long endoscopes veterinarians and owners became aware of the frequency and impact of gastric ulceration in adult horses in the 1990s. Gastric ulceration in horses more closely resembles GERD seen in man and is produced by exposure of the squamous mucosa to acid. In humans the majority of cases of gastric ulcers are caused by infection with Helicobacter pylori, a spiral-shaped, flagellated Gram-negative bacillus that colonizes the gastric mucosa of more than 50% of the human population. Although the majority of infected people are asymptomatic, in some individuals colonization produces gastric inflammation that can evolve to chronic gastritis, peptic ulceration and gastric cancer.7 Helicobacter species have been isolated from feces and stomachs of healthy horses and horses with ulcers.8 In addition, Helicobacter DNA has been found in the stomach and feces of adult horses and foals.9,10 However, a clear and convincing association between Helicobacter colonization and gastric ulcers in horses has not been made. It has been the author’s experience that in a small subpopulation of horses, gastric acid suppressant therapy fails to resolve gastric ulceration until parenteral antimicrobials (trimethoprim sulfa and metronidazole) are added to the treatment regimen. This anecdotal observation suggests that, in a small number of cases, bacteria may colonize ulcer beds, exacerbate ulceration and contribute to a failure to respond to routine treatments. The term equine gastric ulcer syndrome (EGUS) was adopted to describe a group of diseases in foals and horses including erosions and ulcerations in the distal esophagus, non-glandular and glandular stomachs, and proximal duodenum of horses.11 Equine gastric ulcer syndrome results from an unbalance between mucosal protective factors (mucus and bicarbonate production) and aggressive factors (HCl, pepsin and bile acids). In foals the disease is described in highly stressed newborn and in suckling foals.12 In neonatal foals, due to other primary diseases, the signs may be subtle and ulcers can progress and occasionally perforate in the absence of overt clinical signs.12 In suckling and early weanlings foals, lesions are found in the proximal duodenum and pylorus and may result in a functional obstruction causing delayed gastric emptying, requiring surgical bypass of the obstruction in some cases. In adult horses most of the ulcers are located on the squamous portion of the stomach, closer to the margo plicatus. Less commonly, the glandular portion of the stomach can also be affected. Glandular ulcers often are associated with clinical signs and the use of anti-inflammatory agents. Clinical signs of gastric and duodenal ulceration in foals include bruxism, teeth grinding, inappetence, watery diarrhea and abdominal discomfort. Signs of EGUS in adult horses are subtle and not specific. Reported signs in adult horses include acute, chronic and recurrent abdominal pain, diarrhea or loose feces, weight loss, poor appetite, poor hair coat and body condition, obtundation, and decreased performance.13,14 Horses with clinical signs have higher prevalence and severity of gastric ulceration.14 In addition, 49% of horses presented to a referral center for abdominal pain had gastric ulceration; and the prevalence of ulceration in horses responding to medical treatment was higher compared to horses that required surgical treatment.15 Although the history, physical examination and laboratory findings may provide evidence in support of a diagnosis of gastric ulceration, endoscopic examination of the stomach is required for definitive diagnosis. With the availability of two- and three-meter endoscopes, gastric ulcers are now commonly diagnosed in foals and adult horses. Although a two-meter-long scope may reach the stomach of many adult horses, a three-meter-long scope is required to examine the lesser curvature, cardiac orifice, pyloric antrum and proximal duodenum. All feed and forage should be withheld for a minimum of 12 hours and water for 2–4 hours before endoscopy because the presence of feed material within the stomach will hamper complete examination. Distention of the stomach by insufflation with air may improve visualization by lowering the fluid level inside the stomach, exposing a bigger surface area. Feed material can easily attach to the mucosal wall, preventing evaluation of some areas. The use of tap water under pressure by using a 60 mL syringe or an automatic fluid pump attached to the biopsy port of the scope may assist with removal of the feed material. In an attempt to characterize and standardize the severity of gastric ulcers in horses the Equine Gastric Ulcer Council proposed an ulcer grading system16 (Table 47.1; Fig. 47.1) that is commonly used by researchers and practitioners. Table 47.1 Grading system for gastric ulcers developed by the Equine Gastric Ulcer Council16 Recently, a commercial two-part lateral flow immunoassay for the detection of blood in feces of horses became available. The tests use specific antibodies for the detection of equine albumin (source of blood caudal to the common bile duct) or equine hemoglobin (source of blood at any location of the GI tract). However the test has only a moderate negative (72%) and positive (77%) predictive value for the diagnosis of equine gastric ulcer disease.17 The management of gastric ulceration should include, when possible, control or modification of risk factors. Gastric acidity is greatest when horses do not have access to feed material.18 Therefore, continuous feeding or feeding several times a day may prevent or assist in gastric ulcer recovery. Allowing horses access to pasture grazing may also assist in the prevention of gastric ulcers, as one study showed that stall confinement is a risk factor for ulcer formation while turnout to pasture assists in resolution of ulceration.19 High grain-concentrate diets increase plasma gastrin production and promote the production of volatile fatty acids in the stomach, which may contribute to ulcer formation.20 Reducing the total amount of starch given each day as well as the amount provided in each meal may reduce EGUS prevalence. Alfalfa hay has been shown to increased gastric pH, due to the buffer capacity of its calcium and protein contents.21 Therefore an alfalfa hay diet may buffer stomach acidity in horses. Other predisposing factors for ulcer formation include intensive exercise, transportation and the use of NSAIDs. Although limiting exercise may not be feasible, decreasing transportation and using agents to reduce gastric acid production in horses during active competition may be warranted. Avoiding or decreasing NSAID use, and using cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 specific anti-inflammatory drugs may also assist in the prevention or treatment of animals with gastric ulceration. However, management modifications are not always possible and often the treatment and prevention of gastric ulcers relies on agents to increase the gastric pH by reducing production of HCl. Medical treatment is recommended for horses with severe gastric ulcers, horses with clinical signs and horses under stressful conditions; in addition horses at risk of developing ulceration may be treated to prevent the development of ulcers. The initial recommended treatment time for most antiulcer medications is 28 days. Improvement of clinical signs should not be used to discontinue therapy, as clinical signs may improve or resolve faster than healing. If recheck endoscopy is available it may be used to evaluate improvement and adjust the length of treatment. The primary pharmacologic agents used for the treatment of gastric ulcers in horses include histamine type-2 receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors. Both drug types effectively decrease acid production and increase gastric pH in horses.22,23 Proton pump inhibitors completely block gastric acid production by irreversible binding to the enzyme responsible for the terminal step in the acid secretory pathway. In horses the most commonly use histamine type-2 receptor antagonists are cimetidine and ranitidine and the most commonly use proton pump inhibitor is omeprazole. Omeprazole has a longer duration of action and can be administered once a day compared to ranitidine and cimetidine, which require administration three times a day. Two studies have compared omeprazole with cimetidine and ranitidine in racehorses in active training.24,25 Both studies concluded that oral omeprazole once daily was more effective than either cimetidine24 or ranitidine25 in healing gastric squamous mucosal ulcers in racehorses. Omeprazole is a pro-drug that is coverted into an active sulfonamide form by protonation. The active form of omeprazole binds irreversible with the hydrogen-potassium ATPase enzyme in the secretory canaliculi of parietal cells.26 Omeprazole is commercially available for oral administration in a paste form and has been effective for the treatment (4 mg/kg) and prevention (2 mg/kg) of gastric ulceration in racehorses in active racing and training.27 However the commercial paste is expensive and some compounding pharmacies manufacture paste or solution preparations that are considerable cheaper. A study in the author’s laboratory compared the effects of the commercial paste vs a compounded suspension (both at a dose of 4 mg/kg BW) in racehorses in active exercise training. The compounded omeprazole suspension did not decrease the severity of gastric ulceration, whereas gastric ulcers resolved in horses that received the commercial paste (Fig. 47.2).26 In addition, significantly lower blood omeprazole concentrations were detected in horses after administration of the compounded suspension (1.13 µg/mL peak concentration) compared to the commercial paste (2.85 µg/mL peak concentration). A different study comparing the commercial formulation with three generic compounded formulations found inconsistent results, with two of the three generic presentations failing to reduce the pH of gastric contents to a level considered necessary for ulcer healing (mean pH < 4).28 Omeprazole is a lipophilic weak base that degrades rapidly in acidic aqueous solutions. The alkaline pH of the commercial paste (8.43,26 10.229) is higher than the pH of some of the compounded products (3.41,26 5.1–5.728) and it was hypothesized that the lower pH may be responsible for this lower efficacy.26,28 The American Veterinary Medical Association established that compounding may only be performed when no approved use of an animal or human drug is available. In addition, compounding pharmacies are not regulated by the Food and Drug Administration; neither do the products require testing for strength or potency. Therefore veterinarians need to be careful when prescribing compounded medications.29 Relative to the size of the entire gastrointestinal tract, the stomach of the horse is small compared to other species. It is located in the dorsal part of the abdominal cavity and is divided in two parts: squamous (dorsal) and glandular (ventral) regions by the margo plicatus. The squamous region of the stomach is lined by non-glandular stratified squamous epithelium similar to the esophageal mucosa. It does not contain glandular structures and lacks effective protective mechanisms against acid injury. The primary barriers to acid in the squamous epithelium are the intracellular tight junctions and intracellular secretion of bicarbonate ions.30 The ventral region of the stomach is lined by glandular epithelium that secretes HCl, pepsinogen, histamine, gastrin and serotonin. Acid is secreted in the glandular mucosa of the stomach by the parietal cells located in the oxyntic glands. Glands in this region also secrete mucus and bicarbonate that are important for mucosal defense against acid, pepsin and other corrosive agents.31 Hydrogen ions are secreted into the gastric lumen by intracellular canaliculus located in the parietal cell. Acid secretion involves an elevation of intracellular calcium, follow by activation of protein kinase cascades, which trigger the translocation and insertion of the proton pump into the apical membrane of the cell.32 The active transport of H+ across the mucosal membrane is catalyzed by H+, K+-ATPase, and H+ is pumped into the lumen in exchange for K+. The more important regulators for gastric acid production are gastrin, acetylcholine and histamine (Fig. 47.3). Gastric releasing peptide stimulates G cells to produce gastrin; and somatostatin acts on the G cell to inhibit gastrin release. Gastrin acts on acid secretion directly on the parietal cell or indirectly on the enterochomaffin-like cells to produce histamine. Acetylcholine is produced by postganglionic cholinergic muscarinic nerves and also acts directly on the parietal cell or indirectly on the enterochomaffin-like cells. Histamine is produced by the enterochomaffin-like cells located in the lamina propria of the gastric gland and acts directly on the parietal cell.32 The horse’s stomach secretes acid even during the fasted state. Although the pH of gastric juice is acid, it has frequent periods of alkalinization (Fig. 47.4) due to the passage of duodenal fluid (bile and pancreatic secretions) through the pylorus into the stomach (Fig. 47.5).31 Even under fasted conditions, periods of alkaline pH (6–7.5), lasting up to 5 min, can be seen periodically in horses.31 Conjugated bile salts are normally maintained in their dissociated form in the intestine; however at the lower pH of the stomach, they may unionised and become lipid soluble, gaining access to the mucosa.33 It is likely that, in addition to the damage caused by the acid to the mucosa, other factors such as pancreatic enzymes, and activation of pepsinogen and bile salts by acid, are also involved in the formation of gastric mucosal lesions in the stomach. While the squamous mucosa of the horse stomach has limited defense mechanism against corrosive agents, the glandular mucosa has a complex mechanism of protection.34 Cells of the gastric glands secrete and form a mucosal barrier produced by a combination of mucus and bicarbonate. In addition, the gastric mucosa is also protected by prostaglandins that inhibit gastric acid production, increase mucus/bicarbonate secretion, stimulate mucosal repair, prevent swelling by stimulating sodium transport and produce vasodilation.34 Diets high in starch (gain and grain-concentrates) can produce ulcers in horses.35 High concentrate diets are fermented in the stomach by resident bacteria, resulting in production of volatile fatty acids. The volatile fatty acids in a low pH environment have produced damage to the equine gastric squamous mucosa in vitro.36 Risk factors identified for ulcer formation in horses include: history of colic, stress, poor hair coat, picky eater, straw being fed as the only forage, diets high in starch, transportation, stall confinement, intermittent feeding, intensive exercise, racing, illness, and use of NSAIDs.13,17,38 Racehorses in active training or racing are more predisposed to gastric ulceration.39 The area more commonly affected with ulceration in the stomach of horses is the squamous region closer to the margo plicatus, likely because the mucosa in this area is close to the source of gastric acid and lacks effective protective mechanisms. Two recent studies in endurance horses have reported a higher prevalence of glandular lesions than has been reported for horses in other athletic disciplines.37,40 In one of these reports, 27% of the horses had an active bleeding lesion in the glandular mucosa during an examination performed immediately after the end of an endurance race.37

Gastrointestinal diseases of athletic horses

Introduction

Equine gastric ulcer syndrome

Recognition

Physical examination

Laboratory examination and diagnosis

Grade 0

Intact epithelium, no hyperemia (reddening) or hyperkeratosis

Grade 1

Intact epithelium, areas of hyperemia or hyperkeratosis

Grade 2

Small, single or multifocal lesions

Grade 3

Large, single or multifocal lesions, or extensive superficial lesions

Grade 4

Extensive deep ulceration

Treatment and prognosis

Therapy

Etiology and pathophysiology

Epidemiology

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Gastrointestinal diseases of athletic horses