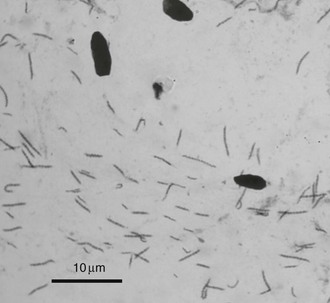

Chapter 124 Currently a direct causal relationship between spiral bacteria and chronic gastritis and vomiting or with gastric neoplasia has not been established firmly in dogs or cats. However, based on clinical experience and several clinical studies evaluating dogs and cats treated for Helicobacter spp. and identifying improvement or resolution of clinical signs, the author believes that gastric Helicobacter spp. can cause or contribute to the clinical signs in some dogs and cats with chronic gastritis and vomiting (Happonen et al, 2000; Jergens et al, 2009; Leib et al, 2007). In addition, a potential relationship between gastric lymphoblastic lymphoma and Helicobacter heilmannii in cats has been proposed (Bridgeford et al, 2008). Although H. pylori has been identified in a research colony of cats, infections in pet dogs and cats with other species of Helicobacter is more common. Gastric Helicobacter spp. usually found in dogs and cats are larger than H. pylori (1.5 to 3 µm). Initially these large spiral bacteria (4 to 10 µm) were called Gastrospirillum hominis but were later reclassified as Helicobacter heilmannii. Other large gastric spiral bacteria such as Helicobacter felis, Helicobacter bizzozeronii, and Helicobacter salomonis are found and are indistinguishable from H. heilmannii using routine light microscopy. Multiple species also can be present within an individual animal. Gastric or duodenal ulceration associated with Helicobacter spp. is rare in dogs and cats, demonstrating a major pathophysiologic difference between H. pylori and the gastric spiral bacteria commonly found in dogs and cats. In addition to the role of Helicobacter spp. in the pathogenesis of gastritis and chronic vomiting in dogs and cats is the potential for zoonotic transmission. Most evidence indicates zoonotic transmission to be very low, but the potential is real. H. heilmannii is a rare cause of gastritis in humans, accounting for approximately 0.1% of cases. An epidemiologic survey of humans with H. heilmannii gastritis showed that contact with dogs and cats was a significant risk factor (Meining et al, 1998). In addition, there was an association between H. heilmannii gastritis and gastric lymphoma, although this relationship could be coincidental (Stolte et al, 1997). Some studies have identified cat ownership as a risk factor for H. pylori infection in humans, whereas others have found contact with dogs or cats not to be a risk factor for H. pylori infection. Although the potential for zoonotic transmission appears slight, until this issue is resolved conclusively, it seems prudent to identify the presence of gastric Helicobacter spp. in dogs and cats during the diagnostic evaluation of chronic vomiting. Gastric brush cytology is the least expensive and most practical diagnostic method with the quickest turnaround time. After completion of an endoscopic examination and collection of biopsy samples from the duodenum and stomach, a brush cytology specimen is collected. A guarded cytology brush is passed through the biopsy channel of the endoscope into the gastric body along the greater curvature. The cytology brush is extended from the sheath and gently rubbed along the mucosa from the antrum toward the fundus, along the greater curvature. Hemorrhagic areas associated with previous biopsy sites should be avoided. The brush is retracted into the protective sheath and withdrawn from the endoscope. The brush is extended from the sheath, gently rubbed across several glass microscope slides, which are air dried, and stained with a rapid Wright stain (Dip Quick stain). The slide is examined under 100× oil immersion. Areas with numerous epithelial cells and large amounts of mucus are examined initially for Helicobacter spp. If present, the spiral bacteria are seen easily. They are usually at least as long as the diameter of a red blood cell, and their classic spiral shape is obvious (Figure 124-1). The number of spiral bacteria can be highly variable, from one every several fields to massive numbers in most fields. At least 10 oil immersion fields are examined on two slides before the specimen is considered negative. Unlike diagnostic tests that involve using a single or several small biopsy samples, brush cytology gathers surface mucus and epithelial cells from a much larger area, increasing the chances for identification of bacteria. Brush cytology was found to be more sensitive than urease testing or histopathologic examination of gastric tissues in identifying Helicobacter spp. organisms in dogs and cats (Happonen et al, 1996). Figure 124-1 Gastric brush cytology specimens stained with Dip Quick stain. Large numbers of spiral bacteria are visible. Cellular debris is scattered throughout the photograph. (With permission from Leib MS, Duncan RB: Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet 27:221, 2005.)

Gastric Helicobacter spp. and Chronic Vomiting in Dogs

Pathogenesis

Diagnostic Tests

Brush Cytology

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Gastric Helicobacter spp. and Chronic Vomiting in Dogs

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue