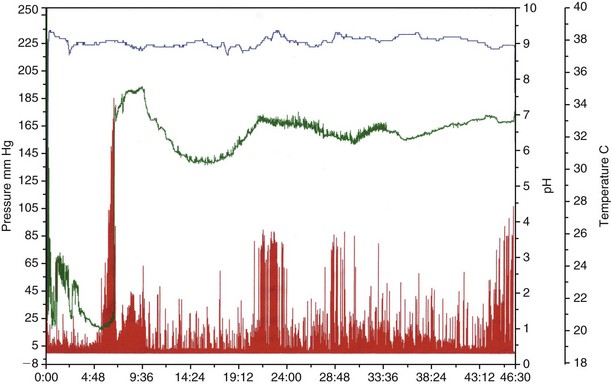

Chapter 125 Signs associated with disorders of gastric motility in dogs and cats are listed in Box 125-1. However, the signs may be difficult to recognize before the problem becomes severe. Primary functional disorders appear to be rare in small animals. Slower gastric emptying occurs in dogs following circumcostal gastropexy performed after gastric dilation-volvulus (GDV). Gastric motility is impaired in the fasting and postprandial phases in these dogs (Hall et al, 1992). However, it has not been established whether this abnormal motility is involved in the etiology of GDV or simply a consequence of surgical treatment. The exact role of gastric dysmotility in canine GDV has not been elucidated to date. Systemic disorders also may affect GI motility. Hypoadrenocorticism often is accompanied by decreased gastric motility. Furthermore, abnormal small intestinal and colonic motility have been shown in dogs with ablation of 66% of renal mass and chronic renal disease, whereas gastric emptying seemed normal. However, it is not known if a larger reduction of functional renal mass, as is observed in clinical cases (>75%), may have negative effects on gastric motility. Finally, delayed gastric emptying may be induced by various medications; opioid analgesics and anticholinergics may interfere with GI neurotransmitters and cause impaired smooth muscle function. Vincristine, a frequently used chemotherapy agent, recently has been shown to decrease gastric antral motility transiently (Tsukamoto et al, 2011). The various methods available to investigate gastric emptying have been reviewed in detail (Wyse et al, 2003). They aim at evaluating the gastric emptying or intestinal transit time of solid food and include radionuclide scintigraphy, radiographic contrast studies (barium meals and barium impregnated polyethylene spheres, or BIPS), and abdominal ultrasound. Gastric emptying also can be measured using indirect techniques relying on duodenal absorption of compounds that subsequently can be detected in the breath (e.g., 13C-octanoid acid) or in the blood (e.g., acetaminophen). Recently, a wireless motility capsule (SmartPill) has been validated for use in dogs (Boillat et al, 2010) (Figure 125-1). Figure 125-1 Wireless motility capsule recording in a young healthy male mixbreed dog. The top line reflects the temperature (in degrees Celsius), the line below represents the pH, while the bottom line shows the pressure profile (in mm Hg). Time is shown on the X axis (in hours [h] and minutes [min]). The massive rise in pH at 6 h 42 min indicates exit of the capsule from the stomach. The slight decline in pH at 9 h 20 min indicates entry into the large bowel. Gastric emptying time was 6 h 38 min, small bowel transit time was 2 h 38 min, and large bowel transit time was 36 h 57 min.

Gastric and Intestinal Motility Disorders

Disorders of Gastric Emptying

Clinical Signs

Etiology

Primary Disorders of Gastric Motility

Secondary Disorders of Gastric Motility

Diseases Affecting Multiple Organ Systems.

Diagnostic Approach

Evaluation of Gastrointestinal Motility

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Gastric and Intestinal Motility Disorders

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue