Teresa Y. Morishita

Galliformes

Galliformes species are characterized as birds that are medium to large bodied, have rounded wings, have a well-developed keel bone, and have strong legs with four digits that are designed for their terrestrial life.17 Galliformes are one of the first bird orders to be associated with humans and among the first domesticated.17 They remain diverse with regard to their domestication, ranging from the common barnyard poultry species to the more exotic species found in zoologic settings and captive breeding programs. In a zoologic setting, aviary collections may include the more exotic members of Galliformes, whereas places such as children’s zoos may have the common domesticated chicken and turkeys. The more exotic Galliformes species are usually housed as breeding pairs, and collections of domesticated Galliformes species are housed in small flocks. It is important to consider disease transmission between domesticated species of Galliformes and that of the exotic Galliformes collection. Although diseases and their treatment and control are often extrapolated from those diseases well described in domestic Galliformes species,5 exotic ones seem to be fairly hardy under captive conditions.

Within Galliformes, relatedness among the various species has been debated. Relatedness has been based on deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA),63 and more recent phylogenetic trees have been based on mitochondrial DNA.26 The major divisions of the Galliformes are found in Box 18-1. For a complete listing of genus and species worldwide, including natural histories, comprehensive pictorial atlases are readily available.11

The majority of exotic Galliformes species housed in zoologic parks are the guans, chalacas, currasows, pheasants, peafowl, and guinea fowl. In some captive conditions, guinea fowl are considered the “watch dogs” of Galliformes and have been used for rodent control and alerting other species to impending danger with their shrill calls.19 In some zoologic settings, guinea fowl are usually kept in mixed exhibits. Peafowls are often allowed free roam access in zoologic settings, and this may present problems if they have contact with both the exotic and domestic species of Galliformes kept on site. The same concern applies to free-roaming jungle fowl.

Clinical Significance of Unique Anatomy and Physiology

Some Galliformes species have portions of their integumentary system that are unfeathered, including areas of the head. The most extreme elaborate unfeathered areas are found in turkeys, with their bare heads, ornamental caruncles, and the snood, a fleshy skin appendage found near the upper beak between the eyes.17 For Galliformes, unfeathered areas of the head may be prone to frost bite in environments with extreme winter conditions.66

Since the Galliformes species are terrestrial birds, their adaption to ground dwelling has been cryptically colored feathers in brown, black, and gray.17 Some Phasianidae, especially the males, are brightly colored in red, yellow, and silver feathered patterns.12,20 The peacock, a member of the Phasianidae family, has elongated uppertail coverts with the characteristic eyespots that are used in mating displays.17 Most young of the Galliformes species are covered in down when they hatch; however, members of the Megapodiidae family are fully feathered and capable of flight when they emerge from their mound nests.17 Although many of the male of the Galliformes species are brightly colored compared with the more drab-colored females, both males and females of guinea fowl are similar in appearance, having the same plumage, markings, and colorations that make visual sexing guinea fowl difficult.19 Guinea fowl also have a unique characteristic of having tiny white dots over their entire plumage.19

The beaks of the Galliformes species are short, stout, and generally conical in shape, with an arched culmen and with the tip of the maxilla slightly overlapping the mandible.17 The beak is used to pick up grains and small insects and does not have the crushing power as seen in other seed eaters.17 In a captive setting, beaks will not overgrow and need not be trimmed unless malocclusion exists.35 The main injury that has been associated with the beak is related to wire gauge size of the housing. If too large a gauge size is used and the bird’s beak may fit through the cage wiring, traumatic damage to the beak may occur if the bird becomes spooked and jerks its beak backward.35 Lacerations of the beak may be prevented with appropriate cage gauge size.35

Galliformes species have digits that are arranged in the anisodactyl position with three digits facing forward and one digit, often referred to as the hind toe, facing backward.17 The hind toe is often reduced in size. In some species within Galliformes, differences exist. In Phasianidae and Numidadae, the hind toe is elevated and not in contact with the ground.17 However, in the Megapodiidae and Cracidae families, the hind toe is on the same level as the ground.17 Some members of the Phasianidae have spurs on the tarsus; and some members such as the grouse have feathered tarsi and digits.17 The spurs do not need to be medically managed but may cause injuries for zoo staff when the bird is captured, handled, or both. If spurs are to be removed, caution should be exercised during surgical removal.9,35

All members of the order Galliformes are known as granivorous birds and have a well-developed muscular ventriculus (gizzard) because of the striated muscle layers.8,17 In addition, Galliformes species have well-developed ceca.8,17 Although domesticated Galliformes species have been provided grit in their diets, it is not required for digestion.35 Under natural exhibit conditions, exotic species may have small stones in their gizzards and observed as incidental findings during necropsy.29 In addition, it should be noted that Galliformes species are curious, and if exposed to environmental conditions they are not accustomed to, they may ingest excessive grass, flooring substrates, and even feathers to form an impaction (blockage) in the gizzard that needs to be surgically removed.29,35,39,40,50,56 This may be prevented by obtaining a history on the previous housing conditions provided to the birds.

Radiographic Anatomy Considerations

The general body-shape of Galliformes is rounded and the visceral organs are compact. Hence, it may be difficult to visualize individual visceral organs such as the heart, liver, and ventriculus.65 The manus is shorter than or about the same length as the antebrachium or the brachium.65 Radiographically, a sesamoid bone is seen proximal to the carpus, located within the tendon of the tensor propatagialis muscle.65 Since the legs of Galliformes were developed for a terrestrial life style, the femur, tibiotarsus, and tarsometatarsus are all relatively long.65 In some birds, the length of the femur may be two thirds the length of the tibiotarsus.65

Behavioral Aspects

Galliformes species have ritualized feeding habits that are incorporated in their courtship behavior and are especially noted in quails, pheasants, and peacocks.12,17 These ritualized feeding behaviors displayed in courtship behavior is often referred to as tidbitting and involves the male bowing in front of the female with wings and tail outstretched to varying degrees, and beak pointing to the ground.17 Guinea fowl are rather aggressive and may chase other Galliformes and bird species away, so care must be used if they are placed in mixed species avian exhibits.19

Husbandry

Husbandry and management requirements for Galliformes depend on the species and numbers. In general, a pair of pheasants would need a minimum of 200 square feet with tragopans needing closer to 400 square feet; for a basic enclosure.20 For smaller Galliformes, 100 to 150 square feet may be adequate.20 One of the most important considerations in facility design is to predator-proof the enclosures and to determine the size of the netting’s gauge and type.20,22 If wire netting is used, it is necessary to extend the netting at least 12 inches into the ground to prevent predators from digging through and gaining access into the exhibit areas.20,22 With regard to the netting gauge, a determination needs to be made if the exhibit is primarily designed to keep the Galliformes species in the enclosure or if the primary purpose is to prevent small birds such as house sparrows from entering the enclosures and having contact with the Galliformes species.35 With recent concerns of diseases such as avian influenza among free-living birds and Galliformes, prevention of pest avian contact is of utmost importance. However, in geographic regions with heavy snow, the concern with exhibit collapse exists if snow is not removed and allowed to accumulate on small-gauge wiring.35 In addition, the smaller gauges will also hinder the public’s clear view of the birds on exhibit. In terms of design, a long aviary with narrow frontage is preferred, as it would provide enough space for the birds to retreat to the back of the exhibit if they need to feel safe.20,35 An aviary with shallow depth and long frontage will provide better viewing but would not allow a retreat area for the birds.20 With multiple adjacent aviaries housing Galliformes, it has been recommended to have a solid partition that is 18 to 24 inches in height to prevent aggression or to have small-gauge netting to prevent contact between adjacent exhibits.20,35 Exotic Galliformes species such as pheasants may be highly aggressive and, if crowded, may display intraspecies aggression and incur skin wounds that could result in gangrenous dermatis.48

Perches should be placed in a sheltered area. Consideration should be given for birds that have long tail feathers. For these birds, perches should not be located close to exhibit walls and caging, as this could damage or break the feathers as the birds turn on their perches.20

Housing requirements are simple. Some species are fairly hardy, and all that is required is a simple A-frame structure.20,23,24,35,40 Those species from neotropical and tropical environments may need supplemental heat during inclement weather. For such species, indoor housing with supplemental heat may be needed, depending on environmental conditions.

Since Galliformes tend to reside in flocks, single bird exhibits should be avoided. A breeding pair for exotic Galliformes is ideal. A single guinea fowl will tend to vocalize more than normally as they prefer to be in flocks, with a minimum of three birds.19 In the case of domestic species such as chickens in the children’s zoo or farm sections, the birds should be kept in all-hen groups. If roosters are to be included in the group, at least two males should be placed in a flock, with six to seven females per male.35,50 Caution should be used in dealing with single-rooster flocks, as these roosters tend to be more aggressive to both keepers and visitors.35,50 Having two roosters in the flock will allow the roosters to establish a pecking order.35,50

Biosecurity and Quarantine

It is of utmost importance to perform the necessary tests to fully evaluate the health and exposure of newly acquired exotic Galliformes during the quarantine period.14,35 The quarantine period may start from a minimum of 2 weeks for commercial and backyard poultry species35,46; this period is insufficient for exotic Galliformes. For exotic Galliformes, or for domestic Galliformes destined for a children’s zoo, a minimum of 45 to 60 days would be more appropriate. The reason for this recommended time is the 2-week incubation time of most documented diseases in domestic Galliformes, and the time needed for diagnostic test result reporting also needs to be taken into account.35 Although domestic poultry have a 2-week to 30-day quarantine period, their prior history is documented, and thus their disease exposure history may already be known.35 In addition, if disease does occur, domestic Galliformes housing areas are more easily cleaned and disinfected.35 However, one of the challenges in housing exotic Galliformes in public displays that recreate their natural settings for enrichment is that they are extremely difficult to thoroughly clean and disinfect once a disease has been established.35,39,40 This is why a complete disease assessment needs to be performed during the quarantine period. Moreover, for collections involving areas of public display, major renovations to the environment may be limited for disease control purposes.35 For example, roundworms may survive in the soil for at least 7 years, and in heavy nematode infestations in Galliformes, it is recommended to turn over the top 3 to 5 inches of soil to reduce exposure of the birds to infective ova and to top-dress (place new floor substrate) the top of the flooring to reduce exposure of birds to infected ova.35,39,40 However, this would be impractical for areas of public display. Hence, the quarantine period is very important to determine the presence of diseases in new acquisitions to prevent and minimize the contamination of the aviary environment.

On arrival, shipping containers should be examined and feces present collected so that the first round of fecal examination may be performed to evaluate for the presence of endoparasites. This should be repeated at 2-week intervals for at least three successive collections to ensure the detection of endoparasites. False-negative test results may occur if the birds were in an early stage of infection, so serial testing is necessary. Table 18-1 lists the recommended tests that should be performed in the quarantine period and the rationale.

TABLE 18-1

Recommended Procedures and Tests for Exotic Galliformes in Quarantine and Duration of Recommended Testing

| Procedure/Test | Rationale | Ideal |

| Physical examination | Examine the birds for external parasites, especially lice and mites. Mites have a wide host range and live also in the environment. If detected while the birds are on exhibit, control may be difficult with restrictions on chemical exposure to species and environment. Early mite infections start near the vent and ventral abdomen region, so scrutinize these areas during physical examination. | Some species may be fractious to handling. Even in the absence of parasite detection, treat with antiparasitic agent, and repeat in 2 weeks because of generalized 2-week life cycles of external parasites. For exotic Galliformes, have at minimum three successive 2-week treatment plan. |

| Serologic testing | Collect serum to determine exposure to Mycoplasma, a bacterium that may be spread via vertical and horizontal transmission and may impact captive breeding programs. If detected, clearing breeders of the infection may be attempted as described for commercial poultry. Although this disease may cause minimal clinical impact as a sole disease, it may impact the severity of other respiratory diseases. Other serologic tests to perform include those for Newcastle disease and avian influenza exposure. | Test all birds on arrival. Allow at least 2 weeks for testing results to be completed. Establish collaborative relationship with state diagnostic laboratories that may perform such tests, as they are commonly used in the commercial poultry industry. Some states monitor for diseases within the state, so costs may be minimal. Collect serum 3 weeks after initial blood collection to detect early infections that may not have been previously detected, as antibody levels did not raise to detectable levels. |

| Hematologic and biochemical values | When collecting blood, also make blood smears to evaluate for blood parasite presence. | Because of the existence of a variety of exotic Galliformes species for which established values have not been determined, it would be helpful to collect “baseline” levels in birds whenever the opportunity arises. Since exotic Galliformes species are not usually handled once on exhibit, the quarantine period is a good opportunity to get species-specific data. |

| Parasite fecal examination | Minimal cost necessitates the need to perform such tests. Some infective ova of nematodes may survive in the soil for prolonged periods, so it is best to detect such infections before the exhibition area becomes “seeded” with parasites, which would necessitate lifelong treatment of the collection. | Treat for nematodes, cestodes, and trematodes on arrival of the birds and 2 weeks thereafter to ensure detection of developing stages. For exotic species, have a minimum three successive, 2-week treatment plan. Check feces before releasing the birds into the exhibit area. |

A physical examination and additional testing, including fecal examination (for internal parasites), serologic monitoring, and hematologic and biochemical monitoring, are highly recommended.35,43,44 The time needed in the quarantine period is well worth the prevention of seeding the exhibit area with infectious agents and parasites.46

Nutrition and Feeding

Although specific diets may be created for each species, it is often difficult to find nutritionists and feed mills, and the feed may be cost prohibitive. The nutritional diets of pheasants most closely align with those of domesticated turkeys, and feeds produced for turkeys provide almost all the basic requirements of most pheasant species.20 Starter diets for chicks usually contain 28% to 30% protein.20 Diets for growing birds contain 20% to 24% protein, whereas protein levels needed for maintenance range from 13% to 15%.20 If breeding of pheasants is required, a 17% to 20% protein level is recommended. Guinea fowl starter diets should contain 24% protein for the first 4 weeks and 22% between 4 and 8 weeks of age.19 Guinea fowl may then be maintained at 18% protein.19

Besides a balanced diet, fresh greens are also recommended.19 Fresh grass clippings may be provided, but caution should be used to ensure that the birds do not gorge on grass as crop and gizzard impactions may occur.35 More digestible green leafy lettuce, along with carrots and fruits such as apples, oranges, bananas, and grapes, is often popular. Mealworms as live insect food also provide enrichment and are recommended for captive birds.20 Overexposure to new items may lead to curiosity and potential ingestion and impaction of indigestible materials.35,50

Since exotic Galliformes species are usually fed balanced rations, the occurrence of nutritional diseases is rare. Nutritional deficiencies may occur if feed storage conditions are inadequate. Food should be stored in a cool, dark, rodent-proof container, away from sun and moisture to avoid degradation of vitamins and mold development, respectively. Feed mixing errors that directly affect the birds or indirectly affect their offspring may occur.27

It is important that newly hatched young Galliformes be directed to water drinkers, and marbles must be placed in water troughs such that the water levels do not cover the marbles, as some young Galliformes, especially guinea fowl, have a tendency to explore the water and will often get their down wet. Having wet down will chill the young chick and may increase chick mortality.35

Restraint and Handling

In general, Galliformes species may be handled without chemical restraint. To restrain Galliformes, the bird should be grasped across the back to control its wings, since they may be easily broken if the bird flaps them to escape.50,66 After gaining control of the bird, one hand should be quickly placed between the bird’s legs, with the legs controlled between the handler’s fingers. The legs should be grasped firmly but loosely and close to the body. The bird should then be gently flipped so that one side of its body is placed against a hard, nonmovable surface.50 Once the bird feels secure, it will become calm. In the case of a fractious bird, it may be necessary to place a dark-colored cloth over its head to keep it calm.50

Although handler injuries are usually not serious, caution should be used when handling Galliformes species with tarsal spurs.50 Handler safety measures should include face and head protection during handling of birds that are nervous and unpredictable.50

It is difficult to capture guinea fowl as they are fearful unless they have experienced extensive handling as young chicks. Guinea fowl should never be picked up by the wings as the feathers surrounding the wings are loosely attached and will result in their loss.19 Unlike in other Galliformes, the legs of guinea fowl are extremely fragile and may be easily broken. To restrain a guinea fowl, one hand should be used to close the wings while pushing the bird’s body to the ground. At the same time, the other hand should be placed over the closed wing to pick the guinea fowl straight up. The key is to prevent the bird from flapping its wings and constantly kicking its legs.19

In a zoologic setting, it may be difficult to monitor the health of Galliformes species that are allowed free-roaming status, including peafowl, jungle fowl, and guinea fowl. Hence, accessing health status of these birds and other birds in the collection is necessary before they are allowed free-roam access.

Surgery and Anesthesia

Flight Restriction

While exotic species of Galliformes tend to be terrestrial species, they are capable of flight for short distances. Most captive Galliformes are housed in aviary situations where escape opportunities are limited and measures for flight control and restriction are unnecessary. However, flight restriction may be needed for those species that may have free access to the grounds. The most common species allowed free-roam access include jungle fowl, peafowl, and guinea fowl. The least invasive flight control method is wing clipping, but it is only a temporary measure. See Chapter 65 for more information on avian deflighting techniques.

Spur Management

In some Galliformes species such as pheasants, peafowl, and jungle fowl, a pointed spur (calcar) projects caudomedially from the medial surface of the tarsometatarsus. The spur is composed of the bony calcarial process that is ankylosed to the tarsusmetatarsus and covered by a sharp pointed horny covering.9,65 Removal of the spur, if deemed necessary, should be considered a surgical procedure. Spurs should never be removed with guillotine-type nail clippers.

Diagnostics

For the diagnosis of diseases in captive exotic Galliformes species, some of the well-developed tests used in the commercial poultry industry may be adapted.

Serologic Monitoring

Serologic monitoring is one of the most important tools for determining disease exposure, chronicity of disease, effectiveness of vaccination programs, and disease epidemiology.44,50,53 To minimize stress in captive species, every instance that calls for the capture of the birds should be used for collection of blood also if such procedures do not stress the birds too much. This will allow for the monitoring of disease and for the banking of serum for disease monitoring or for future disease investigation.35,39,44 Blood collection from Galliformes is fairly simple, and three main sites may be used: the right jugular vein along the neck, the wing (brachial) vein, and the leg (tarsal) vein.21,44 Depending on the size of the bird, each approach has its advantages. In smaller birds such as quails or in young chicks, the jugular vein is the preferred site. The wing vein is most often preferred for adult birds. No more than 1% of a bird’s body weight should be collected (i.e., 1 mL/100 gm), and in general, for the total volume blood collected, a yield of 50% serum may be harvested.21,41

Hematologic and Biochemical Evaluation

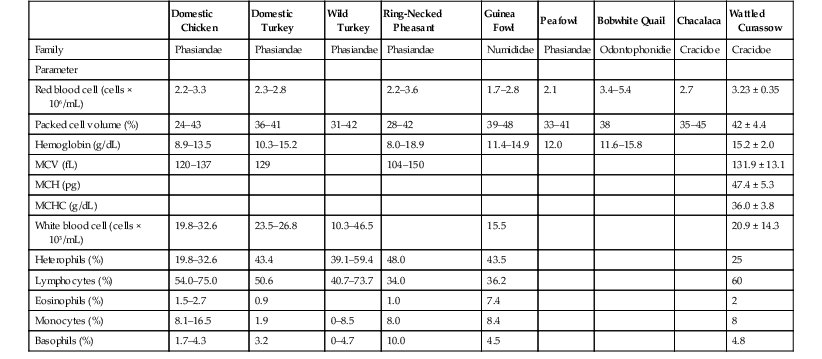

Collection of blood to establish hematologic and biochemical values is important to assess the health of individual birds. It is recommended that a baseline value be established first for each individual species at the time of quarantine because it may be assumed that the bird would be healthy at that point in time. Tables 18-2 and 18-3 provide hematologic and biochemical values for selected exotic Galliformes species as previously reported.1,4,13,16,18,25,68,69

TABLE 18-2

Reference Ranges for Hematology Parameters for Selected Species of Galliformes

| Domestic Chicken | Domestic Turkey | Wild Turkey | Ring-Necked Pheasant | Guinea Fowl | Peafowl | Bobwhite Quail | Chacalaca | Wattled Curassow | |

| Family | Phasiandae | Phasiandae | Phasiandae | Phasiandae | Numididae | Phasiandae | Odontophonidie | Cracidoe | Cracidoe |

| Parameter | |||||||||

| Red blood cell (cells × 106/mL) | 2.2–3.3 | 2.3–2.8 | 2.2–3.6 | 1.7–2.8 | 2.1 | 3.4–5.4 | 2.7 | 3.23 ± 0.35 | |

| Packed cell volume (%) | 24–43 | 36–41 | 31–42 | 28–42 | 39–48 | 33–41 | 38 | 35–45 | 42 ± 4.4 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 8.9–13.5 | 10.3–15.2 | 8.0–18.9 | 11.4–14.9 | 12.0 | 11.6–15.8 | 15.2 ± 2.0 | ||

| MCV (fL) | 120–137 | 129 | 104–150 | 131.9 ± 13.1 | |||||

| MCH (pg) | 47.4 ± 5.3 | ||||||||

| MCHC (g/dL) | 36.0 ± 3.8 | ||||||||

| White blood cell (cells × 103/mL) | 19.8–32.6 | 23.5–26.8 | 10.3–46.5 | 15.5 | 20.9 ± 14.3 | ||||

| Heterophils (%) | 19.8–32.6 | 43.4 | 39.1–59.4 | 48.0 | 43.5 | 25 | |||

| Lymphocytes (%) | 54.0–75.0 | 50.6 | 40.7–73.7 | 34.0 | 36.2 | 60 | |||

| Eosinophils (%) | 1.5–2.7 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 7.4 | 2 | ||||

| Monocytes (%) | 8.1–16.5 | 1.9 | 0–8.5 | 8.0 | 8.4 | 8 | |||

| Basophils (%) | 1.7–4.3 | 3.2 | 0–4.7 | 10.0 | 4.5 | 4.8 |

fl, Femtoliter; g/dL, gram per deciliter; MCH, mean corpuscular hemoglobin; MCHC, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; mL, milliliter; pg, picogram.

From references 1,4,16,18,25,68,69; as summarized by Drew (13) with modifications.

TABLE 18-3

Reference Ranges for Serum Biochemical for Selected Galliformes

| Domestic Chicken | Domestic Turkey | Wild Turkey | Ring-Necked Pheasant | Guinea Fowl | Peafowl | Bobwhite Quail | Chacalaca | Wattled Curassow | |

| Family | Phasiandae | Phasiandae | Phasiandae | Phasiandae | Numididae | Phasiandae | Odontophonidie | Cracidoe | Cracidoe |

| Parameter | |||||||||

| Total protein (g/dL) | 3.3–5.5 | 4.9–7.6 | 3.6–5.5 | 6.9 | 3.5–4.4 | 4.0 + 0.7 | |||

| Albumin (g/dL) | 1.3–2.8 | 3.0–5.9 | 1.1–2.1 | 5.2 | |||||

| Globulin (g/dL) | 1.5–4.1 | 1.7–1.9 | 1.7 | ||||||

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 13.2–23.7 | 11.7–38.7 | 11.4–14.6 | 14.1–15.4 | 11.8 + 1.2 | ||||

| Phosphorus (mg/dL) | 6.2–7.9 | 5.4–7.1 | |||||||

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 131–171 | 149–155 | 164–172 | 149–157 | 154–162 | 158–164 | 161 + 5 | ||

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 3.0–7.3 | 6.0–6.4 | 4.3 + 1.5 | ||||||

| Chloride (mEq/L) | |||||||||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.9–1.8 | 0.8–0.9 | 0.3 + 0.1 | ||||||

| Uric acid (mg/dL) | 2.5–8.1 | 3.4–5.2 | 3–17 | 2.3–3.7 | 2.9–5.1 | 1.8–3.7 | 3.7–7.9 | 10.0 + 3.6 | |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 227–300 | 275–425 | 215–500 | 335–397 | 273–357 | 235–345 | 309 + 47 | ||

| ALT (IU/L) | 34 + 13.6 | ||||||||

| AST (IU/L) | 255–499 | 14 + 6. | |||||||

| GGT (IU/L) | |||||||||

| LDH (IU/L) | 420–1338 | ||||||||

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.3 + 0.1 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree