Chapter 49 Fungal-Like Agents

RHINOSPORIDIUM SEEBERI

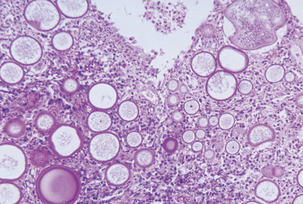

Although polyps have been maintained in tissue culture medium for up to 15 days, actual propagation of the organism has not been successful. Diagnosis therefore is not based on culture of the organism but on the tissue appearance of the organism. In potassium hydroxide (KOH) mounts of crushed polyps, spherules with endospores (sporangium with sporangia) are observed. These spherules may be as large as 350 μm, much larger than those of Coccidioides immitis (Figure 49-1). Rhinosporidium seeberi is visualized in histologic sections with fungal stains such as periodic acid–Schiff and methenamine silver. The tissue response is inflammatory, with evidence of polymorphonuclear cellular infiltration and tissue necrosis. Scarring and granulation tissue are common findings.

FIGURE 49-1 Micrograph of rhinosporidiosis.

(Courtesy Public Health Image Library, PHIL #3107, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, 1965, Martin Hicklin.)

THE GENUS PNEUMOCYSTIS

Because of the lack of an in vitro propagation system, the life cycle of this organism and the subsequent epidemiology of pneumocystosis have not been defined. It appears that the normal habitat is the lung and the only part of the life cycle that is known is that involving the mammalian lung. The proposed life cycle includes a sexual and an asexual growth phase. The two main developmental stages are the trophozoite and the cyst. Trophozoites are produced during the asexual growth phase and can probably replicate by binary fission. The haploid trophozoites also replicate sexually by conjugation, and produce diploid zygotes. Zygotes undergo meiosis and mitosis, resulting in precyst formation. Differentiation into a mature cyst results in the production of up to eight intracystic bodies that are released when the mature cyst ruptures and develop into trophozoites.

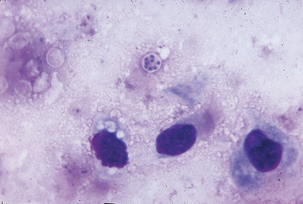

Antemortem diagnosis may be accomplished by careful cytologic examination of fine-needle aspirates of lung biopsy or bronchoalveolar lavage materials. Organisms are small (3-5 μm in diameter) and may exist in low numbers. Wright-Giemsa–type stains best demonstrate trophozoites and intracystic bodies (Figure 49-2). Trophozoites appear as basophilic, dense, oval, or irregular structures having a lobed surface and a single nucleus. Intracystic bodies appear as aggregates of spherical to oval dense basophilic structures against a thick, foamy background. A direct immunofluorescence test can also be applied to bronchoalveolar lavage specimens. Diagnostic immunohistochemical kits are available for use on fixed tissues, and development of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques has given a new alternative for identification of the organism. Serology is an antemortem method to determine exposure to Pneumocystis.

FIGURE 49-2 Giemsa stain of lung impression smear with Pneumocystis carinii.

(Courtesy Public Health Image Library, PHIL #2998, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, 1971, Mae Melvin.)

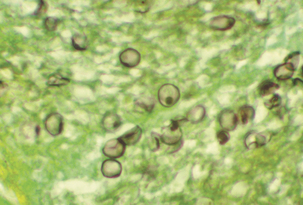

Subacute, interstitial pneumonia with diffuse, alveolar damage, marked macrophage infiltration, and intracellular cysts is observed histologically. Frothy “honeycombed” eosinophilic, intraalveolar material with lymphocytic/plasmacytic interstitial infiltrate suggests P. carinii pneumonia. Fungal stains, such as Gomori methenamine silver, stain the cyst form but not the trophozoite (Figure 49-3). The finding of clusters of nonbudding round to oval to crescent–shaped cysts that appear as “commas” or “parentheses” in alveolar exudates, is confirmatory.

FIGURE 49-3 Cysts of Pneumocystis carinii. Methenamine silver stain.

(Courtesy Public Health Image Library, PHIL #960, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, 1984, Edwin P. Ewing, Jr.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree