Chapter 30

Forensics in Reptile Investigation

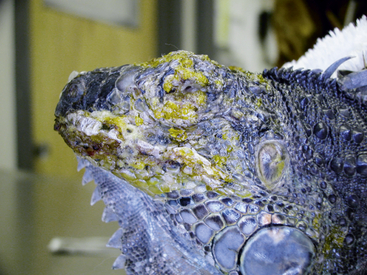

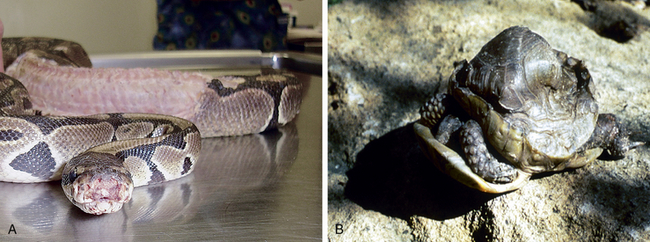

Recognizing neglect and cruelty can be difficult. In some cases, cruelty (Figure 30-1) or neglect (Figure 30-2) may be obvious, but in others, what appears to be neglect can simply be a matter of timing. For example, an inspection of a pet store reveals a Monitor Lizard lying in a feces ridden water bowl. Is this the norm or did the animal happen to defecate moments before the observer noticed the situation (Figure 30-3)? Finally, what may appear to be cruelty may actually be ignorance/stupidity on the part of the owner (Figure 30-4,).

FIGURE 30-1 This iguana, a victim of animal cruelty, was painted blue and had its rear feet and tail cut off. (Photo courtesy Dr. Douglas R. Mader, Marathon Veterinary Hospital, Marathon, Fla.)

FIGURE 30-2 Neglect, such as seen in this iguana that was suffering from a severe mite infestation, can easily be confused with cruelty or abuse. (Photo courtesy Dr. Douglas R. Mader, Marathon Veterinary Hospital, Marathon, Fla).

FIGURE 30-3 This photograph showing a monitor soaking in a feces-filled water bowl could be interpreted as evidence of neglect or cruelty. However, it could also illustrate the issue of timing, if the animal had defecated just moments before the photo was acquired. (Photo courtesy Dr. Douglas R. Mader, Marathon Veterinary Hospital, Marathon, Fla.)

FIGURE 30-4 A, The owner placed a large, live rat unattended in the cage with this python that was not in a hunger state. As a result, the prey became the predator. B, This grossly deformed box turtle has been malnourished its entire life. Although, ostensibly, these cases look like abuse, in actuality, both of these cases are examples of ignorance on the part of the owner. (Photos courtesy Dr. Douglas R. Mader, Marathon Veterinary Hospital, Marathon, Fla.)

Although several publications have addressed forensics in herpetoculture and medicolegal aspects of herpetology in recent years,1–11 there has yet to be a document that specifically defines “herp cruelty”, in the United States. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) does not regulate reptiles and amphibians, and as such, there are no guidelines on caging, nutrition, husbandry requirements, or shipping (Figures 30-5 and 30-6) like there are for other mammals such as dogs and cats. Without written standards, at most, U.S. veterinarians evaluating neglect/cruelty cases can only offer an “opinion.” In the United Kingdom herpetology protection falls under the 1911 Protection of Animals Act that was updated in 2007. The legally important term found within the act is “unnecessary suffering”, for which many people have been prosecuted.

FIGURE 30-5 Evaluation of housing conditions may be a part of a herp-trained veterinarian’s responsibility. (Photo courtesy Dr. T. Tristin.)

FIGURE 30-6 Improper shipping conditions for a collection of amphibians. (Photo courtesy Dr. T. Tristin.)

Until such herp-specific guidelines are developed, veterinarians can use the “Five Freedoms” as a template for assessing the health and welfare of herps. The Five Freedoms evolved from the Report of the Technical Committee to inquire into the welfare of animals kept under intensive livestock husbandry systems (the Brambell Report, December 1965, HMSO London) (Box 30-1). These principles were and are relevant and suggest appropriate measures for any animal species kept by humans—specifically, that all animals must be protected from unnecessary suffering.

Recognition and Reporting of Neglect and Cruelty

As stated by Yoffe-Sharp,12 veterinarians play many vital roles in cases brought to the attention of authorities, including the following:

Recognizing and reporting suspected cases of animal abuse

Recognizing and reporting suspected cases of animal abuse

Assisting at crime scene investigations

Assisting at crime scene investigations

Collecting and documenting evidence

Collecting and documenting evidence

Testifying as expert witnesses in court

Testifying as expert witnesses in court

Recognizing suspected abuse and neglect of family members and reporting to appropriate authorities

Recognizing suspected abuse and neglect of family members and reporting to appropriate authorities

In addition, specifically regarding herp cases, veterinarians’ roles may include the following:

Although reporting cruelty is not required in all U.S. states, the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) advocates the responsibility of the veterinarian to report suspected cases of animal abuse, cruelty, and neglect to the appropriate authorities.13 An excerpt from the AVMA Principles of Veterinary Medical Ethics13 reads as follows: “Veterinarians and their associates should protect the personal privacy of patients and clients. Veterinarians should not reveal confidences unless required to by law or it becomes necessary to protect the health and welfare of other individuals or animals.”

The AVMA Position Statement on Animal Abuse and Animal Neglect13:

Similarly, the American Animal Hospital Association offers the following Position Statement on Animal Abuse14:

Responsibility of the Veterinarian

Yoffe-Sharp12 recommends that veterinarians should

Acquire a working knowledge of applicable laws pertaining to animal cruelty in their state, county, and community

Acquire a working knowledge of applicable laws pertaining to animal cruelty in their state, county, and community

Know which agency in their jurisdiction is responsible for enforcement of animal cruelty laws and develop a working relationship with that agency

Know which agency in their jurisdiction is responsible for enforcement of animal cruelty laws and develop a working relationship with that agency

Establish policies and procedures for recognizing and reporting abuse and provide training for all employees

Establish policies and procedures for recognizing and reporting abuse and provide training for all employees

Documentation

Chain of Custody

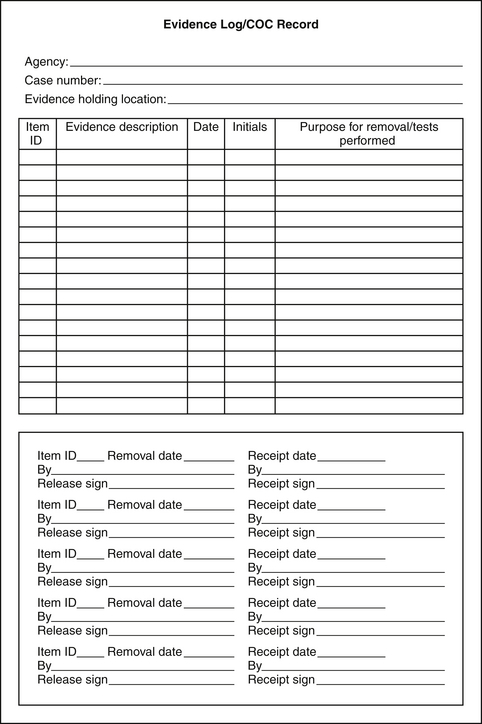

Any evidence related to a crime must follow a chain of custody. This refers to a process of documentation in which the evidence is accounted for at all times, and there is a record of any alteration (e.g., testing; Figure 30-7). Evidence is anything collected or recorded from the animal and includes samples, photographs, radiographs, and the animal itself. It should be the investigating agency or their designee that transports the live or deceased animal to the veterinarian. When that is not possible, a courier service with tracking procedures may be used, and the chain of custody is still maintained.

All evidence must be properly collected, packaged, and labeled, and each item must be recorded in the evidence log (see Figure 30-7). All evidence should be kept in a locked cabinet with restricted access. If the evidence must be kept in a refrigerator or freezer without a lock, it should be located in an area with limited personnel access. A restricted access box may be placed inside the refrigerator or freezer, such as a metal lockbox, that will allow the evidence to be maintained under acceptable conditions. If the evidence is transferred to another person, location, or laboratory, it must be noted in the evidence log with the time, date, and a signature from the sender and/or recipient. This also applies to the body of the animal.

Whenever evidence needs to be transferred, including laboratory samples, chain of custody procedures should be followed. An evidence receipt form should be sent along with the evidence with instructions for the receiving agency/person to fill out the chain of custody section and fax it back (see Figure 30-7). It should be noted on any test request form that the samples are “Evidence,” “Forensic Samples,” or involve a “Criminal Investigation.” This may assist the receiving laboratory to institute certain handling protocols and assign the appropriate person to perform the analysis.

If evidence is removed from storage it should be documented in the evidence log, including the purpose, if opened, and any testing or alteration. If necessary, a sealed evidence package should be opened in a different place from the original opening; the original seal needs to be preserved. This will later provide proof that the original seal was not broken. After the examination is complete, the item is placed back in the original package, sealed with evidence tape, signed, and dated. Evidence must be held until the legal case is over. Because additional legal avenues may be pursued after a case is closed, the prosecuting authority should be consulted before disposing of any evidence.

Photography and Videography

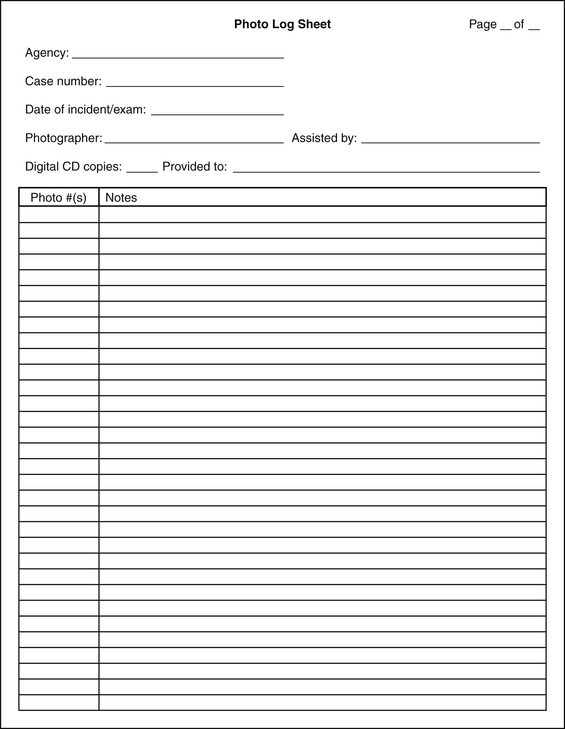

There are some general guidelines regarding photography for legal cases. The photographs may need to be enlarged for court, so the resolution of the photographs should be high enough to prevent loss of detail. After a photograph is taken with a digital camera, the image should be checked for quality and adjustments made as necessary. No photograph should ever be deleted; this is to prevent the appearance that exculpatory evidence was deleted. A photo may be altered only after the original is preserved. Any enhancements or alterations should be documented and saved separately from the original. Several photography software programs automatically record the alteration steps. Photographs should only be of items related to the case; no personal photos should be on the digital card. The photos should be professional: remember, they may end up in court. Care should be taken to avoid including personnel in the photographs, if possible. Hands in the photograph holding or pointing at the area of interest should be avoided; instruments should be used instead. All photographs should be taken at a 90-degree angle to the area of interest. The lighting should be evaluated for each photograph, and reflection off the object or tissue should be avoided. All photographs should be recorded in a photo log (Figure 30-8). The photos may be logged as they are being taken or after all photography is completed.

The photographs should begin with the case information, including the case number, date, and animal ID written on a card or dry-erase board. This first picture with the case and animal information may be taken with or without the animal in the photo. All photographs after this initial picture should only be of the examination of that animal. When cases involve multiple animals, this protocol will ensure consistency of the photographs and reduce the chance of errors. If additional photographs are needed of an animal that has already been photographed, the sequence starts again with the case and animal ID information card. General photos should be taken showing the entire body of the animal, that is, right and left side, front (facial), hind (rear), and dorsal and ventral (if possible) views. Photographs, with and without scale, should be taken of any obvious lesions, abnormal physical findings, and any evidence found on the body.

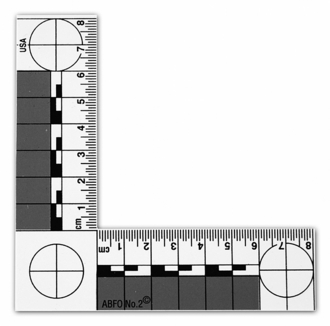

For all photos, it is important to capture the context and location, starting with overall views, then medium views, and finally close-ups. Taking only a close-up view is not useful in court without the reference or context photos. This process of narrowing down the focus and showing perspective may take several photographs to achieve. When physical evidence on the body is photographed, an evidence marker should be in the photo, including the close-up views. Special markers, scales, and pointers for small evidence are available, or a piece of paper with a letter or number system can be created. The markers, with the ID number written on a piece of paper, may be reduced in size to accommodate close-ups. Close-up photographs should be taken with and without a photo scale to show that no evidence was obscured by the scale. The purpose of a photo scale is to show the size of the item. There are special photography scales, such as American Board of Forensic Odontology (ABFO) no. 2 scales (Figure 30-9), that also have symbols and a gray scale to allow correction for size distortion (elongation) and color discrepancies. If a photo scale is not available, other items with known sizes may be used, such as a coin or dollar bill. A macro lens may be used for clear close-ups of small lesions. Because of the sensitivity to movement of fine detail lenses, it is recommended that a mini-tripod be used for stability when photos are taken.

FIGURE 30-9 American Board of Forensic Odontology (ABFO) no. 2 photography scale. (Photo courtesy Dr. Douglas R. Mader, Marathon Veterinary Hospital, Marathon, Fla.)

Examination Documentation

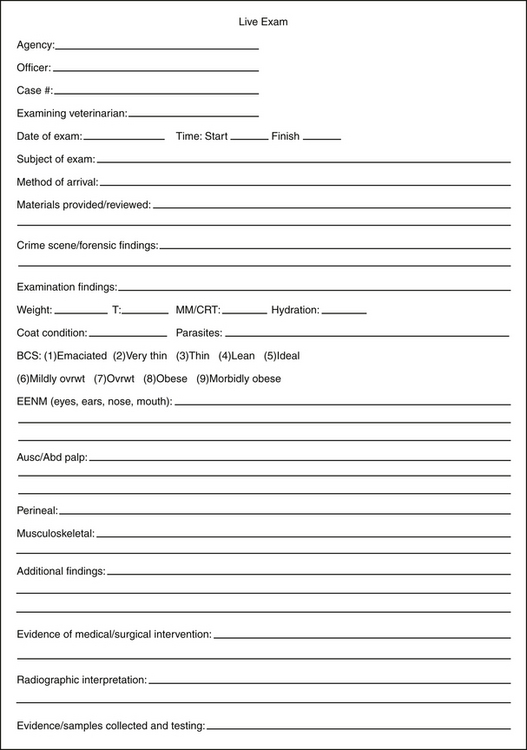

The top of the examination form should have the investigating agency or authority information including their case number and the lead investigator’s name (Figure 30-10). The name of the examining veterinarian and any other parties present for the examination should be noted. The date and time of the examination should be recorded, including the time when the examination is concluded. No examination should be conducted without all the information from the investigators and/or owner, including crime scene findings and photographs, the investigator’s reports, and any witness statements. This information provides the proper context in which the veterinarian can more accurately interpret the examination findings. Anything provided by the investigator should be documented on the form. A description of the animal, including species, sex, coloring, distinguishing marks, and estimated or known age, should be recorded. The basis for age determination should be defined on the document. Details of how the animal arrived should be noted for live and deceased examinations. This includes the person’s name that transported the animal, the method of transport, and packaging details. For deceased animals, the external and internal packaging is recorded and photographs are taken as each layer of packaging is removed. Any tears or leakage of the packaging material should be noted, as well as the degree of decomposition. Any courier information on the package should be photographed and, if possible, removed and placed in the case file.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree