Chapter 30

Flow Cytometry

Flow cytometry is commonly used in human medicine to evaluate patients with leukemia and lymphoma as well as other hematologic diseases and neoplasms. Immunophenotyping (identification of the cell lineage) of neoplastic lymphocytes and leukemic cells is considered indispensable for diagnosis and monitoring of many of these diseases.1 Use of flow cytometry is becoming more common in veterinary medicine and may help differentiate between lymphoid neoplasia and nonneoplastic disorders such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and reactive lymphocytosis. Flow cytometry may also differentiate between T- and B-cell lymphomas and determine the cell line of blasts in acute leukemias. Flow cytometry may also aid in the diagnosis of immune-mediated thrombocytopenia and anemia.

Principles of Flow Cytometry

Flow cytometry measures multiple characteristics of cells and particles in fluid as they pass through a laser beam. Flow cytometry is used in many veterinary hematology analyzers to determine leukocyte differentials and automated reticulocyte counts as part of a complete blood count (CBC). Separation of leukocyte populations is based on differences in light absorption and light scatter properties based on the size and complexity (nuclear shape and cytoplasmic granularity) of the cells. As a cell passes in front of the laser, light scatters at a low angle (forward scatter) depending on the size of the cell and at high angle (side scatter) with increasing cytoplasmic granularity or nuclear lobulation.2 For example, neutrophils are larger than lymphocytes and have more internal complexity (a lobulated nucleus with cytoplasmic granules), so mature neutrophils and lymphocytes can be separated based on light scatter properties alone.3 For automated reticulocyte counts, a dye that stains ribonucleic acid (RNA) is added, allowing immature erythrocytes (reticulocytes) to be separated from mature erythrocytes.4

Sample Collection and Shipping

Submission of a sample with adequate cellularity is necessary to obtain conclusive results. The cells to be analyzed (e.g., circulating atypical lymphocytes for blood samples, lymphoblasts from node aspirates) ideally should be present in a concentration of greater than 3000 per microliter (µL). For patients with lymphoma, sampling of multiple lymph nodes is recommended. Cell preservation is also important, so care should be used when collecting samples with prompt shipping of the sample to the testing facility. Refrigeration of samples (blood, marrow, or tissue aspirates) and shipping with a cold pack is necessary to preserve cell viability and surface proteins for analysis. Samples should be analyzed within 2 to 3 days, if possible, but blood samples and those in transport tubes with preservatives may be viable for up to 5 days. Collecting samples early in the week is preferred to prevent delays in shipping or sample analysis over the weekend. It is also important to collect samples prior to initiation of chemotherapy or treatment with corticosteroids, particularly in patients with lymphoma. In cases where atypical cells are present in both tissue and peripheral blood, submission of a blood sample is only recommended if the atypical cells are present in sufficient numbers. For example, in a dog with peripheral lymphadenopathy diagnosed with lymphoma with more than 90% large, immature lymphocytes (blasts) on FNA cytology of the lymph node, but only low numbers (less than 3,000/µL) of circulating blasts in the peripheral blood, FNA of the lymph node should be submitted rather than peripheral blood.

Sample Processing

At the laboratory, red blood cells (RBCs) in the sample are lysed by using a hypotonic solution, and the cells are incubated with fluorescently labeled antibodies.5 A negative isotype control is used for each fluorescent dye to help identify nonspecific background fluorescence. Antibody panels are not standardized and may differ between laboratories. Some of the most commonly used commercially available surface antibodies for dogs and cats are included in Table 30-1, but other antibodies are also available. A more limited selection of markers is available for cats. Reagents such as propidium iodide and 7-amino-actinomycin D that bind to deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) from lysed cells are also used to ensure that adequate numbers of intact cells are present and to eliminate nonspecific staining of cell fragments or debris.5

TABLE 30-1

Common Commercially Available Surface Markers for Flow Cytometry in Dogs and Cats

| Marker | Canine Cellular Expression | Feline Cellular Expression |

| CD21 | B-cells | B-cells |

| CD5 | All T-cells | All T-cells |

| CD3 | All T-cells | Not available |

| CD4 | Helper T-cells and neutrophils | Helper T-cells |

| CD8 | Cytotoxic T-cells | Cytotoxic T-cells |

| CD14 | Monocytes | Monocytes |

| CD18 | All leukocytes, more strongly in monocytes and granulocytes | Not available |

| CD45 | All leukocytes | Not available |

| CD34 | Stem cells (acute leukemia) | Not available |

Indications for Immunophenotyping by Flow Cytometry

In veterinary medicine, flow cytometry of peripheral blood is useful to evaluate dogs and cats with lymphocytosis or circulating immature cells, if present in sufficient numbers. If only a low number of circulating neoplastic cells are present, these are often difficult to isolate from other cell populations. Clonality assays (polymerase chain reaction [PCR] for antigen receptor rearrangement [PARR] of lymphocytes) may be useful in these cases.6 Flow cytometry is also useful in dogs with lymphoma to determine T-cell or B-cell phenotype but is not typically used for diagnosis of other types of neoplasia such as plasma cell tumor, mast cell tumor, carcinoma, sarcoma, or melanoma.7 These are typically classified by immunohistochemistry, when necessary.

Evaluation of Lymphocytosis in Dogs

In patients with lymphocytosis of small, well-differentiated lymphocytes, it may be difficult to differentiate between reactive lymphocytosis and lymphoid neoplasia on the basis of cell morphology on light microscopy. Evaluation of lymphocyte subsets by flow cytometry in these patients may be helpful to identify neoplasia such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) or the leukemic phase of small cell lymphoma. The lymphocyte population in normal dogs and cats is a mixed population of T-cells (including T-helper cells and cytotoxic T-cell subsets) and B-cells. If a heterogeneous population of lymphocytes is identified, the patient should be evaluated for nonneoplastic (reactive or endocrine) causes of lymphocytosis. Reported differentials for reactive lymphocytosis in dogs include infectious agents (Ehrlichia canis, Leishmania infantum, and Spirocerca lupi) and hypoadrenocorticism.9 If immunophenotyping reveals a homogeneous population of a T-cell subset or B-cells, then neoplastic lymphocytosis is most likely. Identification of lymphocytes that have lost expression of normal surface markers or cells that express an abnormal combination of markers (aberrant phenotype) may also support a diagnosis of neoplasia. In patients with suspected acute leukemia, immunophenotyping is often required for further classification of the cells, as lymphoblasts, myeloblasts, and undifferentiated blasts may all have a similar appearance on light microscopy.

Common immunophenotypes of leukemia have been identified in published studies in dogs. These include small and large cell B-cell lymphocytosis, cytotoxic T-cell lymphocytosis, aberrant T-cell lymphocytosis, and CD34+ acute leukemias. The majority of adult dogs with persistent small cell lymphocytosis have a homogeneous lymphocyte population (more than 80% of the lymphocytes have the same immunophenotype), and may also have aberrant antigen expression indicating neoplastic lymphocytosis.8,9 Recent studies have also found prognostic differences in dogs with neoplastic lymphocytosis based on the immunophenotype.10,11

B-cell Lymphocytosis

Dogs with small cell B-cell lymphocytosis typically have indolent disease, and survival time may exceed 1.5 years.10,11 These patients typically have small lymphocytes with clumped chromatin and normal morphology consistent with chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

In dogs with large cell B-cell lymphocytosis, the reported median survival time with combination chemotherapy for most patients was reported at only 129 days.10 In these dogs, differentiation between primary acute lymphoid leukemia and stage V large cell lymphoma was difficult in this study, as all patients also had peripheral lymphadenopathy.10 The cell morphology in these patients is variable, but most have large lymphocytes (the size of neutrophil or larger) with oval nuclei, fine to finely stippled chromatin, one or more nucleoli, and basophilic cytoplasm.

Cytotoxic T-Cell Lymphocytosis

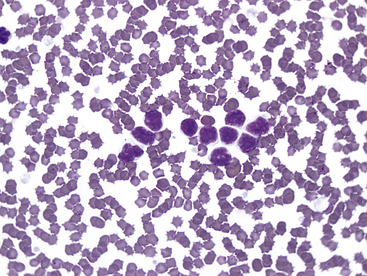

Lymphocytes with this phenotype express CD8, as well as pan–T-cell markers CD3 and CD5. This is the commonly reported type of CLL in dogs.12 Most lymphocytes with this immunophenotype are intermediate in size with oval nuclei, lightly clumped chromatin, no nucleoli, and a scant to moderate amount of lightly basophilic cytoplasm. These cells may contain multiple, fine eosinophilic cytoplasmic granules, and cells with these granules are referred to as granular lymphocytes. See Figure 30-1 for an example. This type of CLL often originates in the spleen, and bone marrow may be spared until late in the disease, so bone marrow cytology often is not helpful to diagnose this type of CLL.13

Figure 30-1 Blood smear (1000×) from a 10-year-old Golden Retriever with persistent lymphocytosis and a lymphocyte count of 27,784/µL at presentation. No other abnormalities were noted on the complete blood count. On immunophenotyping, more than 90% of the lymphocytes coexpressed CD3 and CD8 as well as CD5 and CD45, indicating cytotoxic T-cell lymphocytosis consistent with chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Chronic Ehrlichiosis

Although most commonly seen with CLL, a homogeneous cytotoxic (CD8+) T-cell population may be seen in dogs with E. canis infection.14 Generally, dogs with E. canis infection (or any other cause of nonneoplastic lymphocytosis) have lymphocyte counts less than 30,000/µL.9 Serology and PCR testing are helpful to exclude ehrlichiosis as a cause of persistent lymphocytosis with this phenotype.

Neoplastic Cytotoxic T-Cell Lymphocytosis

Dogs with neoplastic cytotoxic T-cell lymphocytosis most often have indolent disease consistent with CLL, particularly when they present with only a mild or moderate lymphocytosis. In a study that included 33 dogs with this immunophenotype, dogs presenting with greater than 30,000 lymphocytes/µL had shorter median survival (131 days) compared with patients with less than 30,000 lymphocytes/µL (1098 days).10 Another study documented a median survival time of 930 days for this immunophenotype, independent of cell count.11

Aberrant T-Cell Lymphocytosis

Multicolor flow cytometry is particularly helpful in identifying aberrant surface protein expression, which supports a diagnosis of lymphoid neoplasia. T-cells in peripheral blood and lymph nodes normally express CD3 and CD5 with either CD4 (helper T-cells) or CD8 (cytotoxic T-cells). Lack of CD4 or CD8 expression in T-cells is one of the more prevalent aberrant immunophenotypes in dogs with neoplastic lymphocytosis, and loss of CD45 (a marker typically expressed on all leukocytes) is also common in these patients.10 Reported median survival times vary in cases of neoplastic lymphocytosis characterized by an aberrant T-cell phenotype. In one study with 17 dogs, the median survival time was 289 days, but in a smaller study of 6 dogs, it was only 22 days.10,11 Lymphocytes with this immunophenotype cannot be differentiated from small cell B-cell or cytotoxic T-cell lineage on the basis of cell morphology alone. These may be small or intermediate in size and typically lack nucleoli.

Evaluation of Lymphocytosis in Cats

Nonneoplastic Lymphocytosis

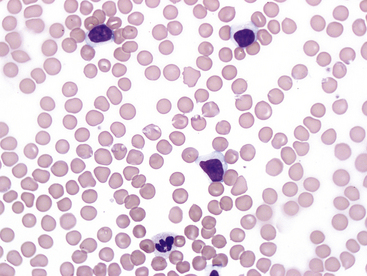

In cats, limited information is available in the literature for chronic lymphocytic leukemia and the incidence of neoplastic versus nonneoplastic lymphocytosis. Physiologic lymphocytosis due to stress or excitement is common in young healthy cats, but this is typically transient and not identified on repeat samplings. Persistent lymphocytosis may be nonneoplastic or associated with lymphoid neoplasia. Potential causes of persistent nonneoplastic or reactive lymphocytosis in cats include infectious agents such as hemotropic Mycoplasma, Cytauxzoon felis, Toxoplasma gondii, feline leukemia virus (FeLV) or feline immunodeficiency virus, immune-mediated disease, hypoadrenocorticism, hyperthyroidism, and methimazole therapy.9,15,16 The lymphocytes in cats with reactive lymphocytosis are typically small and have normal morphology (Figure 30-2). In these cases, a heterogeneous lymphocyte population is expected on flow cytometry (Figure 30-3). These cats may have shifts in the ratio of helper T-cells and cytotoxic T-cells or increased numbers of B-cells when compared with normal cats.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree