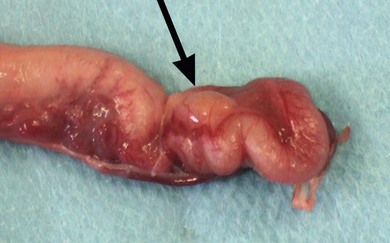

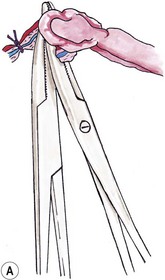

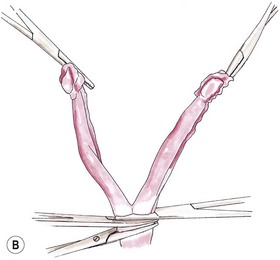

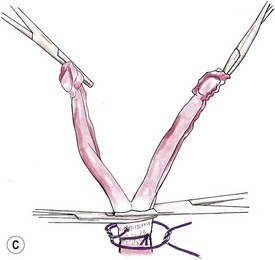

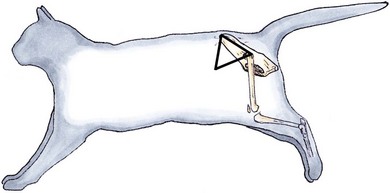

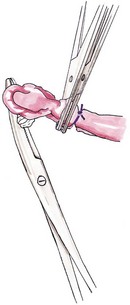

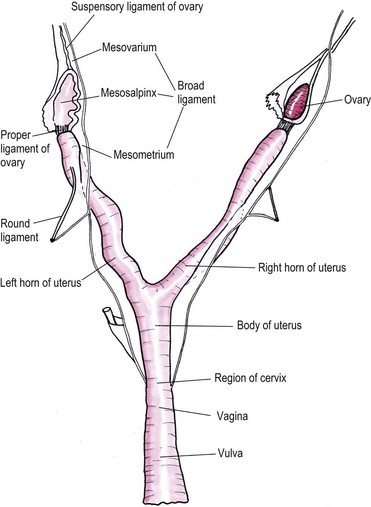

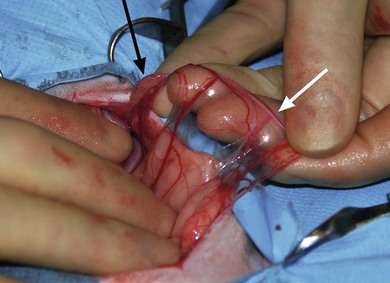

Chapter 40 The female reproductive tract consists of the ovaries, oviducts, uterus, vagina, urogenital sinus, and vulva (Fig. 40-1). The ovaries lie caudal to the kidneys. They are small oval bodies about 1 cm in length.1 The left ovary is usually more caudal than the right one, in keeping with the position of the kidneys. The ovaries are supported by a part of the broad ligament, the mesovarium. A narrow tube, the oviduct, with a funnel shape infundibulum, encircles the ovary. The oviduct ascends along the infundibular side of the ovary, bends over its cranial end and descends along the opposite side where at the caudal end of the ovary it joins the uterus. The ovary is held to the horn of the uterus by the proper ligament, a part of the broad ligament that extends cranially as the suspensory ligament to insert on the middle part of the last one or two ribs. The horn of the uterus is supported by a part of the broad ligament known as the mesometrium. There is also a round ligament, a thickening in the edge of a peritoneal fold, which derives from the broad ligament. The round ligament extends from the cranial end of the uterine horn and runs caudally to the internal inguinal ring. The right and left horns of the uterus join medially to form the body of the uterus. This lies ventral to the colon and rectum and dorsal to the bladder. It extends into the cranial end of the pelvis where it projects into the vagina forming a prominent papilla, the cervix. Figure 40-1 The feline reproductive tract. (From Crouch JE. (1969) Text Atlas of Cat Anatomy. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger.) Cats are a seasonal polyestrus species and induced ovulators. The average age of puberty is variable, but usually starts when the cat reaches 2.3–2.5 kg in weight and is between six and nine months of age.2 Breeds like the Siamese or Burmese appear to be more precocious, reaching puberty at lower weights and younger ages than breeds like the Persian, which may not have their first estrous cycle until 18 months of age. However, the main influencing factor is day length: increasing hours of daylight usually stimulate estrous cycles. In the absence of pregnancy or false pregnancy cats will show repeated estrous cycles every two to three weeks throughout the spring, summer, and autumn.2 The physical examination should look for signs of vulval abnormalities such as enlargement or discharge and abdominal palpation is performed for uterine enlargement. Mammary glands are examined for general enlargement or focal masses (see Chapter 21). Vaginal smear evaluation is less useful in queens for determining stage of estrus for breeding management, particularly as the act of carrying out the procedure can affect the cycle. Hematological and biochemical analysis of blood for evidence of sepsis or other systemic abnormalities with conditions such as pyometra is indicated and hormone levels are assayed in cases of retained ovarian remnant syndrome and potentially cystic ovaries. Radiography is of fairly limited value for the female genital tract investigation, but it may show uterine enlargement. Occasionally, sutures at ovarian vessels or the uterine body may mineralize and therefore be radiopaque. Fetuses are visible between 36 and 45 days and a skull count will give the fetal number (Fig. 40-2). Figure 40-2 Two fetal feline skulls are visible on the abdominal radiograph of this pregnant cat, which therefore must be at least 36–45 days into gestation. Ultrasonography is of more use for investigation of organ size, tissue texture, and the presence of fluid. It can be used to investigate the ovaries and uterus for masses or fluid accumulation. It is also useful to confirm pregnancy, but is less helpful in differentiating between hydrometra, mucometra, pyometra, and hemometra.3 Ultrasound analysis of uterine fluid is unreliable in determining cellular make up, and differentiation is best made on the basis of clinical signs, results of examination, and laboratory analyses. Ovarian agenesis is rare and results in permanent anestrus and infertility. Small ovarian remnants containing fibrous tissue may be identified at laparotomy or laparoscopy.4 Ovarian hypoplasia has been reported in the queen5 and phenotypically normal queens may have non-functional ovaries secondary to chromosomal abnormalities.6 Ovarian cysts are common and their frequency increases with age.6 There are two main types: follicular cysts that arise from mature or atretic follicles,7 and other cysts not of ovarian origin. True follicular cysts are associated with hyperestrogenism if cells lining the cyst secrete estrogen5 and may be associated with exaggerated sexual behavior and prolonged estrus. Administration of progestagen may inhibit the luteinizing hormone surge necessary to induce ovulation and may cause formation of follicular cysts.7 Other cysts, not of ovarian origin, are remnants of mesonephric and rete tubules.8 These cysts are endocrinologically inactive and do not produce clinical signs. The cysts may be detected incidentally at ovariectomy (Fig. 40-3). In animals exhibiting hyperestrogenism, the diagnosis is made on the basis of clinical signs, measurement of plasma estrogen concentrations or demonstration of persistent cornification of vaginal epithelial cells.8 Large cysts may be detected by ultrasound. Human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) may be administered to induce ovulation and thereby treat the cyst but in most cases ovariectomy or the use of progestagens to suppress the clinical signs is necessary.8 Tumors of the ovary are classified on the basis of their cell of origin as epithelial, germ cell, or sex cord stromal and all types have been seen in the cat. The most frequent types seen in queens are granulosa cell tumors, which can metastasise.9 In the largest review of 22 ovarian tumors, a single cat had bilateral cystadenomas of epithelial origin, seven animals had dysgerminomas or teratomas that are germ cell tumors, and 14 animals had granulosa cell tumors and interstitial gland tumors, which are neoplasms of sex cord stromal origin.9 Four of the cats with granulosa cell tumors had clinical evidence of hormonal disturbance. Cats may have signs of persistent estrus, cystic endometrial hyperplasia, and bilaterally symmetrical alopecia.10 Onset of estrus (lordosis, rolling, posturing, excessive vocalization) after gonadectomy is a complication related to a retained ovarian remnant. It is more common after ovariohysterectomy than ovariectomy as the incision made for the former technique is more caudal and access to the ovaries is more difficult. One unproven theory is that there are accessory ovaries that may be small and located in the proper ligament of the ovary; once the normal ovary has been removed these accessory structures may become functional.11 It is also possible for dropped ovarian tissue to become functional,12 although all the cases reported in the literature have had residual ovarian tissue at one or both pedicles.13 Ultrasound is useful for diagnosis and may reveal a cystic structure caudal to the kidney. The diagnosis is also supported by hormonal assays. In the queen, resting serum progesterone values are of little value unless the queen has been bred or induced to ovulate after showing signs of estrus.14 An alternative method of diagnosis is to perform a hormonal stimulation test. In the queen during the breeding season cyclical activity occurs every two to three weeks, and at this time the queen can be readily stimulated to ovulate by the administration of exogenous gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) or hCG. Elevated plasma progesterone concentrations one week after such treatment should confirm the presence of ovarian tissue.15 At surgery, a thorough exploration of the peritoneal cavity is essential, checking the caudal poles of the kidneys, the omentum, and the peritoneal walls. The ovarian remnants are usually found adjacent to the previously ligated pedicle.16 Suspected congenital anomalies of the uterus were identified in 0.09% (49/53 258) of female cats.17 Uterine anomalies identified included unicornuate uterus (33 cats) (Fig. 40-4), segmental agenesis of one uterine horn (15 cats), and uterine horn hypoplasia (one cat). These lesions are often only identified at exploratory laparotomy as they rarely cause clinical signs. Queens may still be fertile if the lesion is unilateral. Figure 40-4 Unicornuate uterus in a stray female cat. An ovariohysterectomy performed through a flank incision had to be converted to a midline incision due to failure to locate the contralateral uterine horn. The ovary is arrowed (black) and there is a structure resembling a round ligament (white arrow) in the mesometrium but no uterine horn identifiable. Most cats affected with uterine neoplasia are intact and are middle aged or older.18 Malignant endometrial adenocarcinoma is the most common endometrial uterine tumor; mixed Müllerian tumors (adenosarcoma) have also been reported.18 Myometrial tumors include benign tumors such as leiomyomas and malignant leiomyosarcomas. Other more unusual uterine neoplasms or neoplastic-like lesions include lymphosarcoma, adenomyosis (refers to the presence of endometrium within the myometrium) and endometrial polyps. Uterine neoplasia may be associated with infertility, pyometra, a persistent hemorrhagic vulvar discharge and straining, and abdominal or pelvic masses. Ovariohysterectomy (see Box 40-1) is the treatment of choice. Prognosis for endometrial adenocarcinoma is guarded. In one retrospective study 50% of adenocarcinomas had metastasized at presentation and only two out of the eight cats survived for longer than five months.18 Cystic endometrial hyperplasia and pyometra (CEH-P) complex is the most frequent and important endometrial disorder in cats and is a sequel to progesterone simulation of the endometrium, and ascending uterine infection by vaginal bacteria19,20 or anogenital contamination. It is more common in older cats21,22 and is uncommon in winter when queens are acyclic. Approximately half the cases are seen in unmated queens, which is unusual as there should be no luteal phase in these animals, but queens may ovulate spontaneously without mating.8 In one study of 20 queens presenting with CEH-P, all affected cats were in diestrus.23 The prevalence of CEH-P in entire female cats increases with age, and most cases of pyometra or endometritis in cats are associated with retained corpora lutea.22 Endogenous ovarian steroid hormones and their derivatives, especially progestogens used to control or suppress estrus, may enhance CEH-P and mammary tumor genesis in cats. The risk of CEH-P is variable and related to the particular progestogen administered, route of administration, amount, frequency and duration of treatment. Megestrol acetate tablets were used as an estrus suppressing agent in 244 cats in Norway in 1974. A weekly dose of 2.5 mg megestrol acetate was given for at least 30 weeks. One cat developed pyometra after three years of treatment with the preparation.24 One queen developed CEH-P, ovarian cysts, mammary adenoma, fibrosarcoma and cystic-papillary adenocarcinoma after continual administration of medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) for nine years.25 Experimentally, uterine changes were seen in prepubertally ovariectomized cats after administration of only six weeks of oral megestrol acetate.26 In another ovariectomized cat, pyometra developed at three years of age, the cat had been treated with proligestone for a dermatologic condition for two years prior to this disease developing.27 The most common signs noted by owners include vaginal discharge, anorexia, and lethargy.28 The malodorous vaginal discharge usually makes diagnosis easy, although the queen will often fastidiously clean her perineum.8 Estrus may have occurred within four weeks of the discharge appearing. Physical examination in early cases may just reveal thickening of the uterine wall, due to endometrial hyperplasia with glandular dilatation, and no or minimal clinical signs. In later cases vaginal discharge (Fig. 40-8), abdominal distension, dehydration, a palpable uterus, and pyrexia are the commonest findings.28 Great care must be exercised when palpating the abdomen in order not to rupture the uterus.

Female genital tract

Surgical anatomy

Reproductive cycle

General considerations

Diagnostic imaging

Surgical diseases of the ovaries

Congenital ovarian abnormalities

Ovarian cysts

Ovarian tumors

Ovarian remnant syndrome

Surgical diseases of the uterus

Congenital anomalies of the uterus

Uterine tumors

Cystic endometrial hyperplasia and pyometra

Clinical signs and investigations

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Female genital tract