CHAPTER 34 Feline Zoonotic Diseases and Prevention of Transmission

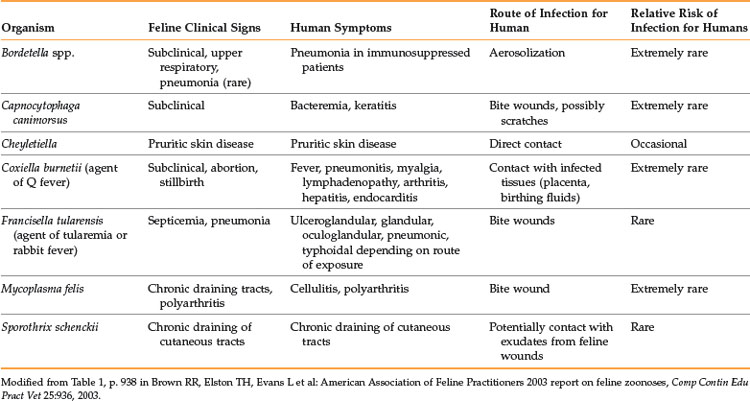

Zoonoses are estimated to make up approximately 75% of today’s emerging infectious diseases. These infectious agents can be transmitted by many different animals, including wildlife, exotic pets, and even traditional pets, such as dogs and cats. Recent studies have shown that cats, both healthy and with diarrhea, can shed zoonotic organisms in their feces. Between 13% and 40% of the cats examined were shedding at least one zoonotic, enteric pathogen.18,36 Although the prevalence of shedding was variable for the specific pathogens, numerous organisms, including Toxocara cati, Giardia, Cryptosporidium, Salmonella, and Campylobacter were identified. This chapter will highlight transmission routes of zoonotic diseases that are commonly associated with domestic cats and what steps can be taken to reduce exposure and transmission (Box 34-1). Additional zoonotic infections are rarely associated with cats (Table 34-1), and more information on these can be found in the American Association of Feline Practitioners 2003 Report on Feline Zoonoses.6

BOX 34-1 Precautions to Reduce the Risk of Contracting a Zoonotic Disease from a Domestic Cat12

• Wash hands after handling cats and before eating.

• Annual checkups and fecal exams should be performed for all cats.

• Rabies vaccinations should be kept current.

• Flea and tick control should be performed.

• Do not allow a cat to lick your face, food utensils, or plate.

• Seek medical attention for cat bites.

• Cats should be fed cooked or commercially processed food.

• Fecal material should be removed from litter boxes daily.

• Dispose of fecal material in a location where water supplies will not be contaminated.

• Clean litter boxes periodically with scalding water and detergent.

• Avoid handling unfamiliar cats, especially those that appear sick.

• Do not allow cats to drink from the toilet.

• Have the cat’s claws trimmed frequently, or consider the use of soft nail caps.

Cat Bites

Although dog bites account for approximately 80% of reported animal bites, cats are the second most common animal reported to cause bites.32 Because cats typically cause puncture wounds when biting, introduction of bacteria deeply into the tissues of the wound is common. Infection rates for cat bites have been reported to range from 30% to 50%, while infection of wounds resulting from dog bites is reportedly lower, 2% to 4%. Pasteurella multocida is the most common bacteria isolated from wounds resulting from cat bites and can cause sepsis, meningitis, and septic arthritis among other complications. Cat bites to the hands often require extensive treatment and are more likely than dog bites to result in complications, such as cellulitis, osteomyelitis, and tenosynovitis.32

Prevention of cat bites can often be achieved by understanding feline behavior, using sedation in fractious cats when appropriate, and wearing thick gloves, such as those worn by welders, to prevent penetration of teeth into hands or forearms. Despite these efforts, cat bites will still occur and should be treated as soon as possible. Delaying treatment is a risk factor for infection and other complications. Pain, swelling, erythema, and swelling of local lymph nodes can occur within 1 to 2 hours of a cat bite. Wound care is essential, and the use of prophylactic antibiotics is still controversial. However, one study that examined a small number of humans who had been bitten by cats found that 67% of those not treated with antibiotics developed infection, while 0% of those treated with antibiotics developed infection.14 Additionally, postexposure prophylaxis for rabies virus may be indicated, depending on the vaccination history of the cat and the circumstances of the bite. The victim’s history of tetanus prophylaxis should also be reviewed. Treatment for cat bites will vary from case to case, but all should include aggressive and careful wound care (e.g., cleaning, irrigation and débridement when necessary) and measures to prevent infection with bacteria, such as Pasteurella multocida or rabies virus.

Bacterial Zoonoses

Bartonella henselae is the most common etiologic agent of cat scratch disease (CSD), but other Bartonella spp. have been found in cats, including B. clarridgeiae, B. koehlerae, and B. weissii.6 Seroprevalence among domestic cats in the United States can vary but has been reported to be as high as 81%.6 Young cats are more commonly bacteremic, and most human cases are associated with kitten exposure. Fleas will feed on bacteremic cats, and the bacteria can then replicate in the gut of fleas and survive in flea feces for days. Human infection occurs after the bite or scratch of a cat, which allows introduction of the bacteria into the skin and subcutaneous tissue (Figure 34-1).11 The bacteria are typically found in flea feces located on the cat (under the claws, in the mouth). Cat scratch disease is usually self-limiting in immune-competent individuals but can lead to atypical and serious consequences in immune-suppressed individuals, including bacillary angiomatosis and bacillary peliosis.16 CSD can most effectively be prevented by maintaining good flea and tick prevention in cats and encouraging gentle play that does not involve the owner’s hands or feet to reduce biting and scratching, especially with kittens. Nails can also be kept trimmed to reduce the likelihood of skin penetration. Additionally, immune-compromised individuals who want to obtain a cat should be encouraged to adopt an adult cat, because they are less likely to be bacteremic.

Yersinia pestis causes plague and can lead to different forms of clinical disease in humans and cats, including bubonic, bacteremic, and pneumonic plague. Plague must be treated with antibiotics or the infection can be rapidly fatal. Human plague is typically associated with exposure to wild rodent fleas; however, exposure to domestic cats can also be a risk factor.11,17 A study that examined human cases of plague in the western United States found that approximately 8% of the reported cases were attributable to contact with domestic cats.17 Exposure occurred through bites, scratches, or other contact with infected cats. Feline and human exposure to Y. pestis, especially in the western United States where plague is endemic, can be reduced by maintaining good flea and tick prevention, keeping cats indoors to reduce exposure to prey species, such as rodents (and associated fleas), and encouraging gentle play.

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is an increasing problem and concern in human medicine, and the role of domestic animals in transmission is increasingly being examined.30 Many studies have focused on canine carriage of or infection with MRSA,24,28 but studies have also identified MRSA in domestic cats.29,33,37,38 Although no definitive evidence of transmission of MRSA from a cat to a human is available, reports of identical isolates in humans and their pets suggest that transmission between species is likely.15,33 Cats likely acquire MRSA from interactions with humans, and a recent study examined risk factors associated with MRSA infections in dogs and cats.34 Dogs and cats with methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) infections were used as unmatched controls for the MRSA cases. The study found that risk factors associated with MRSA infections included number of courses of antibiotics received, number of days admitted to a veterinary clinic, and having received a surgical implant. Of the 197 animals in the study, only 64 were cats (29 MRSA cases, 34 MSSA controls), and data from dogs and cats were combined for analysis. Further research is needed to determine what risk factors might specifically be associated with MRSA infection in cats. Cats can potentially spread MRSA to humans in home or nursing care settings, although the risk is still likely much less than obtaining infection from other humans. Disposable gloves should be worn when possible, but thorough hand washing has been shown to be the most effective method to prevent the spread of MRSA.3 Fomites and environmental surfaces are not typically associated with the transmission of MRSA and routine cleaning and decontamination is sufficient. Additionally, appropriate screening (culture and sensitivity) of clinical patients, both feline and human, can reduce the transmission of MRSA.

Historically, numerous texts have cited Chlamydophila felis as a zoonotic pathogen. Little evidence has been published to support this claim. A recent review of the literature found only seven cases of human disease associated with C. felis.7 Of those seven cases, only one was definitively diagnosed to be caused by C. felis. The human patient had chronic conjunctivitis and was immune-suppressed. Based on the prevalence of C. felis infections in cats, particularly kittens, risk of disease in humans is low. Precautions to limit exposure to cats with respiratory and ocular infections should be taken for individuals that are immune-compromised.

Although group A Streptococcus has been implicated as zoonoses transmitted from a dog, no literature is available confirming the spread of this bacteria from a cat to a human.27 Transmission of group A Streptococcus from a cat to a human is likely extremely rare.6 Exposure to other, less common zoonotic bacteria, such as Salmonella spp., Yersinia enterocolitica, Helicobacter spp., and Campylobacter spp. can be reduced by

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree