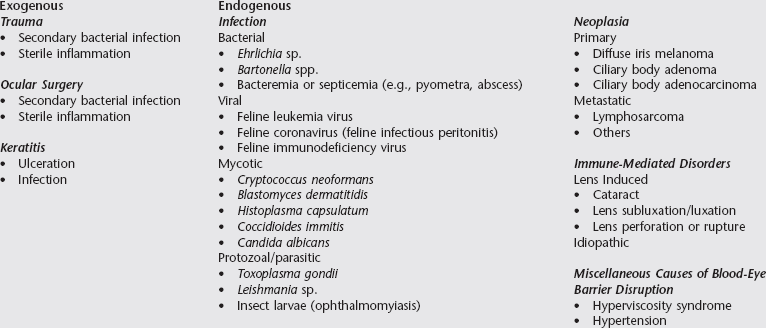

Chapter 250 Uveitis is a painful, vision-threatening disease common in cats. Previous reports suggest that 40% to 70% of feline uveitis cases are associated with a systemic illness. A thorough workup to eliminate infectious causes is imperative because treatment of idiopathic uveitis is directed toward immunosuppression. Owners should be prepared for a potentially expensive diagnostic workup in which a definitive diagnosis is not identified. Some causes of uveitis in cats are different from those identified in the dog (see Chapter 249). Causes of feline uveitis generally are subdivided into the categories of trauma, infection, immune-mediated disease, and neoplasia (Box 250-1). Some causes can be identified by history (trauma) or ocular examination (trauma, lens disorders, neoplasia). Correlating infectious disease with uveitis is more challenging. Infectious causes generally cannot be differentiated by ocular findings alone, so the history, physical examination findings, and results of a complete blood count, urinalysis, and serum biochemical panel should be used to guide further diagnostic testing such as serologic studies, aqueous or vitreous humor analysis, radiography, ocular ultrasonography, and histopathologic evaluation. Ocular fluids can be used for cytologic analysis, culture and sensitivity testing, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay, and determination of antibody content.

Feline Uveitis

Diagnosis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree