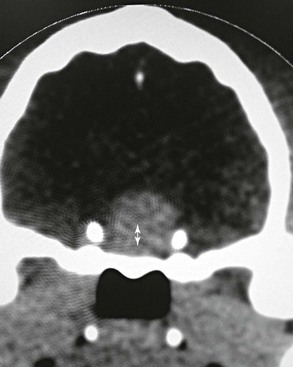

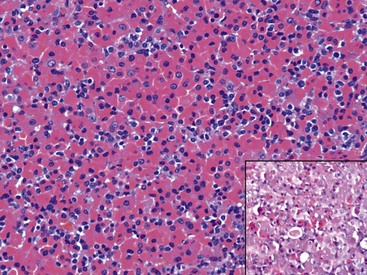

Chapter 49 Feline hypersomatotropism or acromegaly is recognized as an important alternative cause of feline DM largely as a result of two more recent prevalence studies (Niessen et al, 2007a; Berg et al, 2007). Hypersomatotropism refers to the pathologic overproduction and subsequent secretion of growth hormone (GH), which leads to the clinical syndrome of acromegaly. The excess GH, among other effects, causes a state of insulin resistance, which eventually results in DM. Most cats with GH hypersecretion are initially considered to have diabetes. The existence of individual nondiabetic acromegalic cases has been mentioned anecdotally, but the true prevalence of such cases is largely unknown. Because excess GH is diagnosed in a large proportion of cats that do not yet show the typical acromegalic phenotype, using the term hypersomatotropism instead of acromegaly might be more appropriate, although the terms are often used interchangeably. GH induces the production of the peptide insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) (mainly by the liver and only in the presence of sufficient portal insulin concentrations). Serum IGF-1 concentrations are elevated in most acromegalic cats. The authors and colleagues performed a screening study among diabetic cats with variable glycemic control (from good to bad) (Niessen et al, 2007a); 59 of 184 (32%) assessed diabetic cats had IGF-1 concentrations strongly suggestive of acromegaly (>1000 ng/ml). Of these 59 cats, a subpopulation (n = 18) was more closely evaluated with intracranial contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and serum GH measurement to establish conclusively the diagnosis of hypersomatotropism. The diagnosis was subsequently confirmed in 94% of these more carefully assessed cases, proving the original estimation of prevalence, made on the basis of increased IGF-1 concentrations only, to be close to the true prevalence in this diabetic cat population in the United Kingdom. A retrospective North American study indicated that 26% of diabetic cats in the United States seemed to have acromegaly (Berg et al, 2007). Continued monitoring of diabetic cats in British first-line veterinary practices by the authors’ research group has enabled assessment of more than 1200 serum samples of diabetic cats and has substantiated further a prevalence ratio of approximately 25%. This is very important information for any veterinary practitioner because a diagnosis of hypersomatotropism has a huge impact on prognosis and management of the diabetic cat in question (see section on Treatment and Prognosis later). The authors advocate routine screening of diabetic cats for the possible presence of hypersomatotropism, just as screening is done for urinary tract infections in diabetics, the presence of an adrenal tumor in cases with hyperadrenocorticism, or any underlying disease in cases with immune-mediated hemolytic anemia. However, the characteristics and dynamics of serum total IGF-1 concentration measurements as a screening tool should be taken into account (see subsequent section on Diagnosis). Traditionally, acromegaly in cats has been seen as a process caused by excess endogenous GH secretion caused by a pituitary adenoma (Figure 49-1). Until more recently, all reported cases that were subjected to postmortem examination, although bearing in mind the paucity of such reports, suggested this to be the case. A more systematic evaluation of pituitary histopathology in a larger number of patients is currently ongoing and indicates that a minority of cases lack the histopathologic features of a concrete acidophilic adenoma. Instead, acidophilic hyperplasia has been found in these cats (Figure 49-2), which phenotypically in terms of facial and other physical features were indistinguishable from other acromegalic cats (although a typical acromegalic phenotype is not persistently present; see the section on Signalment and Presentation next). If there are at least two underlying etiologic mechanisms, questions arise over a possible interrelationship between them (e.g., hyperplasia becoming adenoma?). A comparison with current hypotheses on the etiology of feline hyperthyroidism is tempting in this regard. Given the fact that feline hyperthyroidism often affects both thyroid glands (albeit not always at the same time), it can be hypothesized that there is a suprathyroidal process driving the disease. Similarly, hypersomatotropism could be hypothesized to originate from the pituitary itself or to be driven by a suprahypophyseal process, possibly located in the hypothalamus. Figure 49-1 Transverse CT image of the brain of a cat with hypersomatotropism demonstrating the presence of a pituitary tumor (double arrow) at the level of the pituitary fossa. Figure 49-2 Microscopic image of the pituitary of a cat with hypersomatotropism demonstrating clear dominance of acidophils (red-staining cells that produce GH) instead of the expected mix of acidophils and basophils (deep blue–staining cells) in a healthy pituitary (inset). (Hematoxylin and eosin staining, magnification ×400.) Most reported feline acromegalic patients have been middle-aged to older male neutered domestic short hair cats with DM, although various breeds have been documented to be affected (Table 49-1). The presence of insulin-resistant DM has been shown to be a definite indicator for the presence of hypersomatotropism. Nevertheless, although in the authors’ dedicated Acromegalic Cat Clinic insulin resistance is frequently a presenting sign, when routinely measuring IGF-1 in all diabetic cats, a significant number of acromegalic patients can be found that appear insulin sensitive at the time of the initial diagnosis. This finding may relate to “catching” these animals at an early time during their disease process, when hyperglycemia and insulin resistance–induced β-cell dysfunction and hyperglycemia-induced insulin resistance have not yet taken their toll. It is also known that hypersomatotropism-induced changes show a particularly gradual and slow onset. This might also be an explanation for the fact that a “typical” acromegalic phenotype is not consistently present. Previous failure to screen more subtle cases can explain our misconception about what an acromegalic cat should always look like. To illustrate the point of gradual onset, duration of clinical signs in the initial group of cats seen by the authors’ research group ranged widely from 2 to 42 months with owners and attending clinicians often remaining unaware of any ongoing morphologic changes (Niessen et al, 2007a; Niessen, 2010). It seems tempting to draw comparisons to feline hyperthyroidism, where we currently rarely see the extreme hyperthyroid cat phenotype, possibly owing to increased preparedness to screen for this disease in elderly cats and increased awareness among clinicians and owners. Commonly encountered yet not consistently present clinical signs, assumed to be directly or indirectly caused by the excess of anabolic and catabolic GH and anabolic IGF-1, are denoted in Figure 49-3. The detected polyphagia might be extreme. Especially weight gain despite poor glycemic control should be a trigger to alert clinicians for the possible presence of acromegaly. TABLE 49-1 Signalment Data and Insulin Requirements of 59 Acromegalic Cats

Feline Hypersomatotropism and Acromegaly

Prevalence

Etiology

Signalment and Presentation

Gender

47 male neutered, 6 female neutered, 5 intact males, 1 unknown

Breed

52 DSH, 3 domestic long hair, 4 unknown

Age (years)

Median, 11 (range, 6-17)

Body weight (kg)

Median, 5.8 (range, 3.5-9.2)

Insulin dose (total per injection)

Median 7 U BID (range, 1-35 U BID)

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree