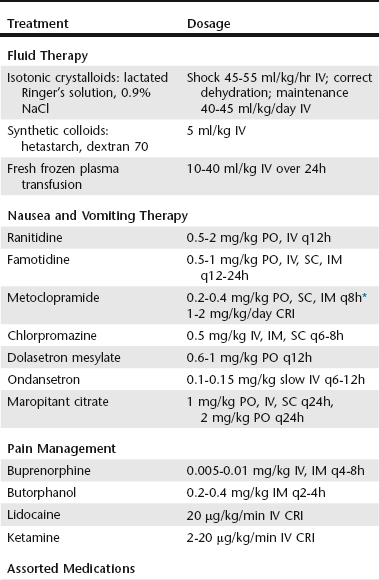

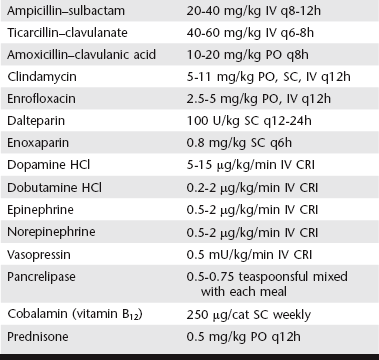

Chapter 138 The core therapy for pancreatitis without complications is supportive and symptomatic. Intravenous fluid is used to restore circulating blood volume, antiemetic medications are used to control nausea and vomiting, and pain relief is provided as needed (Table 138-1). Although less frequently detected than in dogs, potentially because cats have less definitive indicators of pain, abdominal pain can contribute to persistent inappetence, and these cats improve with therapy. The author uses buprenorphine or butorphanol as first-line pain relief medication in cats with mild to moderate pancreatitis. Nutritional support is an important component of therapy. Restriction of oral food and water intake in a nonvomiting cat is not considered necessary; rather, oral intake of food is encouraged. Fasting cats with pancreatitis can lead to development of malnutrition, intestinal atrophy, bacterial translocation, and hepatic lipidosis. With mild to moderate pancreatitis, appetite stimulants are often effective to encourage voluntary intake of food. However, with persistent inappetence for more than 3 to 4 days, placement of an esophageal or gastric feeding tube (percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy [PEG]) should be considered. The ideal dietary composition to feed cats with pancreatitis has not been determined; however, in contrast to dogs, marked fat restriction is likely not necessary. Easily digested, enteral diets currently are recommended. Furthermore, for cats with mild to moderate pancreatitis, the author does not treat with antibiotics or corticosteroids (see section on Areas of Uncertainty later in the chapter). TABLE 138-1 Medical Therapies for Feline Pancreatitis CRI, Constant rate infusion; IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous; PO, by mouth; SC, subcutaneous.

Feline Exocrine Pancreatic Disorders

Treatment of Mild to Moderate Feline Pancreatitis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree