Chapter 8 Feline Cardiomyopathy

FELINE CARDIOMYOPATHIES

Clinical Classification and Pathophysiology

Key Point

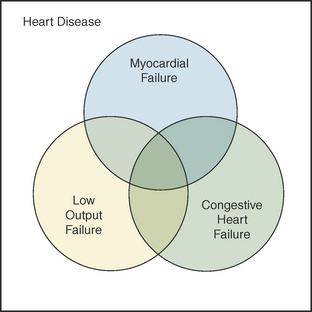

It is important to realize that heart failure and myocardial failure represent heart disease, and that heart failure, either congestive or low-output, may, in some cases, be a result of myocardial failure; however, heart failure can be, and often is, present in the absence of myocardial failure. Similarly, myocardial failure may be present in association with or in the absence of heart failure (Figure 8-1).

Signalment and Presenting Complaints

Physical Examination

Ancillary Tests

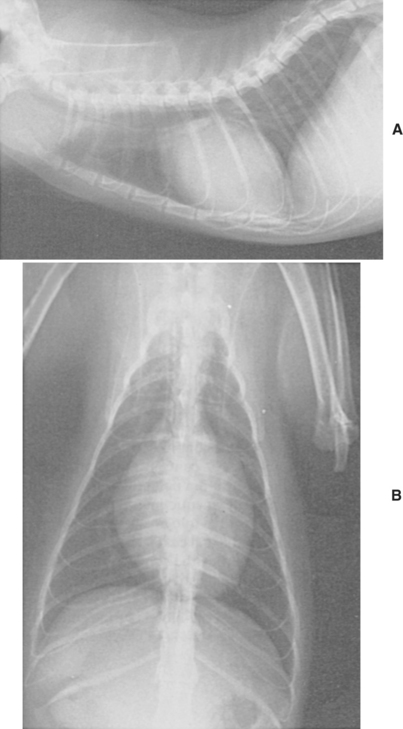

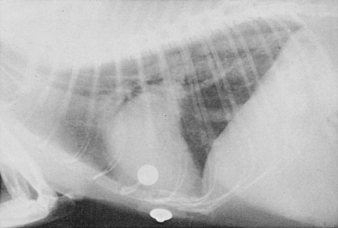

• Thoracic radiography and electrocardiography may direct or reinforce suspicion that a cardiac disorder is present. They may also further characterize the disorder and alert the clinician to secondary ramifications that may require attention; however, neither electrocardiography nor thoracic radiography provides adequate evidence for ruling out, confirming, or classifying feline cardiac disease. Contrast radiography or, preferably, echocardiography, is required to confirm or rule out and categorize myocardial disease.

• Electrocardiography often shows:

• Ventricular arrhythmias are common but are generally mild with relatively infrequent single premature ventricular contractions.

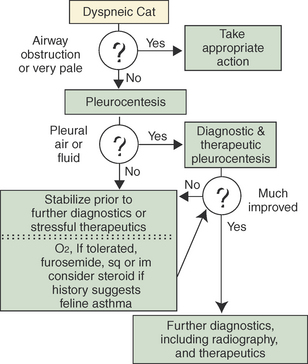

• Thoracic radiography is most useful for detecting gross cardiac enlargement and clinical sequelae to cardiac dysfunction (e.g., pulmonary venous congestion, pulmonary edema, enlarged great veins, pleural effusion) (Figures 8-2 and 8-3). Restraint for radiographic procedures can be life threatening to dyspneic cats. Extreme caution should be taken before proceeding with radiography. The author often delays radiography until after stabilizing the patient (Figure 8-4). Diagnostic and potentially therapeutic thoracocentesis should precede radiography in dyspneic cats.

Therapy

• Therapy should be based upon the clinical and functional classification of the disease process in the individual patient and not by following a standard approach based solely upon the diagnosis.

• Dyspneic cats are easily stressed and may acutely deteriorate and die if stressful diagnostic or therapeutic interventions are initiated too early. An algorithm for management of the dyspneic cat is presented in Figure 8-4.

• Maintenance therapy is generally aimed at minimizing signs and prevent acute crisis. Lower doses of furosemide (6.25 mg twice a day to 12.5 mg three times a day PO) are indicated for chronic maintenance control of CHF. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors (enalapril 0.25 to 0.50 mg/kg PO every 24 to 48 hours or benazepril 0.25 to 0.50 mg/kg PO every 24 hours) are also quite effective in cats with CHF. Antiarrhythmic drugs may be indicated to control significant arrhythmias. Inotropic agents may be indicated in patients with myocardial failure or low-output heart failure.

HYPERTROPHIC CARDIOMYOPATHY

Clinical Classification and Pathophysiology

• Sudden death may occur in any individual and may be unrelated to disease severity. The incidence of sudden death in cats with HCM is unknown.

Echocardiography

• Cats with severe HCM have papillary muscle hypertrophy, markedly thickened LV walls (7 to 10 mm), and usually an enlarged left atrium (Figure 8-5). The hypertrophy can be global, affecting all areas of the LV wall or can be more regional or segmental. Segmental forms can have the entire or a region of the interventricular septum or free wall primarily affected, the apex primarily affected, or the papillary muscles (and often the adjacent free wall) primarily affected. Papillary muscle hypertrophy may be the only manifestation of the disease.

• SAM of the mitral valve may be identified by two-dimensional or, more commonly, by M-mode examination (Figure 8-6). Color flow Doppler echocardiography can be used to demonstrate the hemodynamic abnormalities associated with SAM. Two turbulent jets originating from the LV outflow tract are seen—one regurgitating back into the left atrium and the other projecting into the aorta. Spectral Doppler can be used to determine the pressure gradient across the region of dynamic subaortic stenosis produced by the SAM. The pressure gradient roughly correlates with the severity of the SAM although it can be quite labile, changing with the cat’s level of excitement. SAM is not present in all cats with HCM. The majority of cats with severe HCM have SAM. However, on the other end of the spectrum, some cats develop SAM before they have any evidence of wall thickening, when their papillary muscles are thickened or long. Although the basilar region of the interventricular septum is often thickened in diastole in cats with HCM, the basilar LV outflow tract does not need to be narrowed for SAM to occur.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree