40 Feeding orphan and sick foals

Introduction

The neonatal foal has a high metabolic rate and low hepatic glycogen reserves that only last a few hours (Ousey 2003). Newborn foals are dependent on frequent ingestion of good quality colostrum and then milk. Foals that fail to nurse even for a few hours will rapidly become hypoglycemic, hypovolemic, hypothermic and start to break down body tissue to meet their metabolic needs. During the first week of life, healthy foals suckle five to seven times per hour with each bout lasting just under 2 minutes (Carson & Wood Gush 1983). Over the first month of life, the frequency and duration of the suckling bouts decreases as the foals suckle more efficiently.

Ingestion of adequate quantities of good quality colostrum within the first few hours of life is essential for transfer of maternally derived immunoglobulins (transfer of passive immunity). Thoroughbred mares produce an average of 1–2 liters of colostrum. For maximum efficiency of this specialized but short-lived process for transfer of colostral antibodies, foals should ingest colostrum within 4 hours of birth. Colostrum provides immunoglobulins, complement, lysozyme and lactoferrin and large numbers of B-lymphocytes that are essential for the development of the foal’s immune system. It also contains growth factors and hormones important for development and maturation of the gastrointestinal tract. Ingestion of the non-nutrient factors in colostrum plays a vital role in the preparation of the gut of the newborn foal for digestion of enteral feed (Ousey 2006).

During the first 24 hours post partum foals consume about 15% of their bodyweight as milk (8 liters for a 50-kg foal); this increases to 12–15 liters by the end of the first week of life (Ousey et al 1996). The first month of life is a period of very rapid growth. Thoroughbred foals gain 1.5–2 kg/day (Jelan et al 1996, Martin Rosset & Young 2007), and most Thoroughbred foals will have doubled their birthweight by a month of age. Growth rate in healthy foals is breed, age and month of birth dependent (Chapter 12 provides data on normal growth rates of foals).

From about 2 days of age foals begin nibbling feed, grass and hay copying the feeding behavior of the dam. They start being able to digest solid feed from about 3 weeks of age. Levels of lactase and cellobiase increase in the fetus until birth (Roberts 1975) and then steadily decline from 4 months of age reflecting the change in the foal’s nutrient sources. Hind gut fermentation is not fully established until foals are 3–4 months of age.

It is well established that in order to produce a sound, healthy athlete a smooth growth curve should be maintained rather than periods of restriction and compensatory growth. Although moderate restriction in growth can be compensated for to some extent, capacity for compensation decreases with age. In general, differences in growth rates have little influence on mature size after the rapid neonatal growth phase is completed (Martin Rosset 2005). The reader is referred elsewhere in this book for a more complete discussion on foal growth and development (Chapter 12).

The orphan foal

What to feed

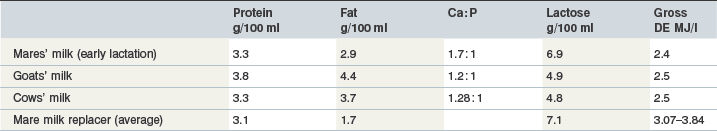

First, in newborn foals it is important to ensure ingestion of adequate quantities of good quality colostrum. In foals >18 hours of age, blood samples should be taken to determine immunoglobulin G concentrations. Mare milk replacers are available worldwide and are preferred when mare’s milk is not available. If mare milk replacers are not immediately available, either unmodified goat milk or semi skimmed (2% fat) cow milk with 20 g/l of dextrose added can be used. Sugar (sucrose) should not be used as young foals lack the enzymes to digest sucrose (Table 40-1).

How to feed

Ousey (1999, 2003) recommends that foals under 2 days of age are fed hourly, then every 2 hours for a further 12 days, after which there should be a gradual decrease in the frequency and increase in the volume fed such that by 8 weeks of age the foal is receiving four feeds daily.

In the authors’ experience, an average daily gain (ADG) >2 kg/day is excessive for a Thoroughbred foal up to 30 days of age (see Chapter 12). For other breeds, data on ADG should be consulted. Farm-specific data on foal growth rates provides the best guide. Alternatively, many international feed companies are able to provide optimum growth curves for various breeds. To avoid excessive or erratic growth rate, the foal should be weighed at least weekly, with feeding rates adjusted as needed.

Foals digest mare’s milk very efficiently (e.g. gross energy [GE] digestibility of 97–99%). However, GE digestibility is lower (approximately 90%) for the first few days of feeding when foals are provided mare milk replacer (Ousey 2006).

Fostering

• Temperament – it is important that there is no risk of injury to the foal or personnel;

• Disease risk – the mare should be screened for risk of EHV 1, strangles and other infectious disease; and

• Stage of lactation – if there is a significant disparity between the stage of lactation and foal age it may be necessary to consider mineral supplementation as milk mineral levels change throughout lactation.

1. Withhold milk from the foal for 1–2 hours prior to introduction to the foster mare.

3. Ensure the mare has easy access to a plentiful supply of hay/feed and water.

4. Have plenty of assistance available when the foal is first introduced to the mare.

5. In some cases carefully fitted hobbles may be helpful.

6. Strip the mare’s udder and cover the foal with her milk.

7. Don’t allow the mare to sniff the foal until a bond is established.

8. Take the mare outside to hand graze her with the foal close by.

Kelly (1999) provides further details of fostering techniques.

Hand rearing

Manufacturers of mare milk replacer provide guidelines on quantities of milk to be fed. With newborn foals it is sensible to gradually increase the quantities fed over the first few days and follow directions regarding the concentration of replacer used. Naylor and Bell (1985) suggest that milk replacer should be fed at 10–15% dilution which is greater than recommended by some manufacturers, although over the last few years, manufacturer’s recommendations have changed to be more in line with this recommendation.

Monitoring growth and development

It is important to monitor weight and height regularly and compare to standard growth curves for breed and sex. The use of condition scoring is also a useful technique. Similar growth curves can be expected for hand-reared foals to those reared on mares (Cymbaluk et al 1993). However in the author’s experience it is a common complication for inexperienced personnel to feed hand-reared foals to appetite, which tends to produce excessive growth rates and associated problems (e.g., physitis). As mentioned, it is important to adjust feeding in accordance with growth rate.

One study found that fostered Thoroughbred foals grew more rapidly than those reared on their dams by 0.0366 kg/day. The authors suggested that the nurse mares (e.g., part and pure bred Tennessee Walkers) are selected for their mothering and milk producing ability, whereas Thoroughbred dams are selected on race performance (Willard et al 2005). In the UK, cobs or larger ponies are most commonly used as foster mares, selected principally for placid temperament and mothering ability.

Sick neonatal foals

Requirements of the sick neonatal foal

Healthy foals aged 1–4 days spend approximately 12 hours standing and active, increasing to nearly 14 hours per day by day 7, whereas sick foals are often recumbent for much of the time. This behavioral difference reduces energy expenditure by approximately two thirds. On the other hand, environmental temperatures below the lower critical temperature (24°C in sick foals) will increase metabolic rate and so can increase energy requirements for maintenance (Ousey 1997, Ousey et al 1997).

Although studies on the requirements of sick foals are sparse, research suggests that the energy requirements of sick neonatal foals are considerably less than their healthy counterparts. Studies of immature foals and foals with perinatal asphyxia syndrome showed they have a lower metabolic rate, requiring only 260–290 kJ/kg/day (13–14.5 MJ/day for a 50 kg foal) compared to 540–600 kJ/kg/day for healthy foals (Ousey et al 1996, Ousey 2003).

A recent study using indirect calorimetry in sick foals reported energy requirements of approximately 188 kJ/kg/day (Paradis 2001). Historically, it was thought that conditions such as sepsis and systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) in young as well as mature patients produced a hypermetabolic state and therefore increased energy requirements. However, recent studies (Taylor et al 2003, Turi et al 2001) in children have refuted this theory, finding that children do not become hypermetabolic during critical illness. Turi et al (2001) speculated that this is due to diversion of energy for growth into the recovery process.

Recent studies in humans having found that the overfeeding of critically ill patients has an adverse affect on outcome (Dandona et al 2005). Similarly, McKenzie & Geor (2009) have suggested a conservative approach to calorie provision for sick neonatal foals. Providing excess carbohydrate can result in hyperglycemia, which may increase production of proinflammatory cytokines and increase production of CO2, which can worsen hypercapnia in foals with respiratory compromise. Excessive dietary protein increases protein catabolism which can produce azotemia, while excessive feeding of lipids results in hypertriglyceridemia. One study reported that triglyceride concentrations >200 mg/l (>2.25 mmol/l) were associated with non-survival in neonatal foals receiving parenteral nutrition (Myers et al 2009).

Mare’s milk has high carbohydrate (lactose) content. Insulin secreted by the beta cells in the pancreas is essential for regulation and homeostasis of blood glucose in the face of high carbohydrate intake. Maturation of beta cells in the pancreas occurs very late in gestation and is dependent on the prepartum cortisol surge which prepares the fetus for birth in the few days before parturition (Holdstock et al 2004, Fowden et al 2005).

Buechner-Maxwell and Thatcher (2004) have suggested that crude protein requirements for neonates are 4–6 g protein/100 non-protein calories. However, other authors have recommended a lower protein requirement (2–5 g/kg/day) for foals with normal plasma protein concentrations, and a higher rate of provision (6.5 g/kg/day) for sick neonates that are hypoproteinemic (Stratton-Phelps 2008). The criteria for diagnosis of hypoproteinemia will depend on factors such as foal age, disease process, and laboratory reference ranges.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree