3 Eyelids – introduction

An understanding of the basic anatomy and physiology of the eyelids is important since so many common ophthalmic problems are encountered in this area, especially in dogs, but less frequently in cats and rabbits as well. The tremendous variation in conformation exacerbated by selective breeding for specific appearance has contributed to the numerous pathological conditions in the area. These can be primarily ocular, such as entropion (rolling in of the eyelids) or distichiasis (extra eyelashes along the eyelid margin) or can be secondary to skin diseases or immune-mediated conditions for example.

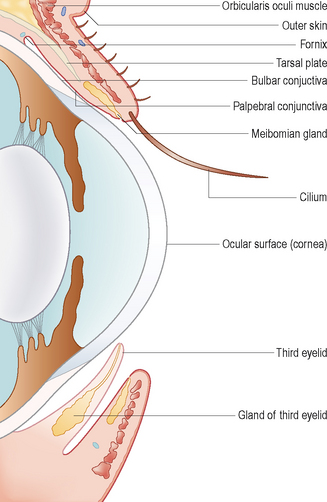

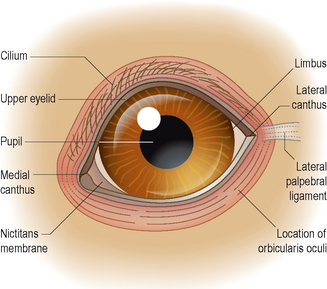

The eyelids are dorsal and ventral folds of skin lined with palpebral conjunctiva and they form the palpebral fissure in which the globe is situated (Figure 3.1). The normal outline of the palpebral fissure is almond shaped (Figure 3.2) but many different variations occur with pedigree animals. The skin should be only loosely adherent to underlying structures but again this can vary from being excessively loose (e.g. in the Saint Bernard) to being very tight (e.g. the miniature poodle). The upper eyelid is more mobile than the lower in most species. A fibrous layer for support, the tarsal plate, is present within the eyelids. This is less well developed in dogs than cats.

The eyelids have several functions. Clearly protection is important, along with the distribution of the tear film (assisting corneal nutrition) and propulsion of tears towards the nasolacrimal punctae for drainage. Foreign bodies such as dust and debris are removed via blinking. Closure of the eyelids reduces visual stimuli and assists sleeping while the cilia around the eyelids are important tactile organs.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree