CHAPTER 192 Examination of the Foal with Colic

Unfortunately, horses can be affected by colic from the first day of life until the last. Evaluation and treatment of acute abdominal pain in foals is somewhat different from that in adult horses because of their size, pain tolerance, and the types of diseases foals acquire. The purpose of this chapter is to attempt to differentiate the medically manageable foal with colic from the foal requiring surgery. This discrimination is especially important in foals because of their predisposition for adhesion formation following abdominal surgery. The decision to treat medically or surgically is resolved by synthesizing information concerning the foal’s history, results of diagnostic tests, and, most important, the physical examination.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Thoracic auscultation should be performed on the right and left sides of the thorax to evaluate the heart and lungs. Mean heart rate is 100 beats per minute during the first 30 days of life and decreases to 60 to 70 beats per minute by age 2 to 3 months. A high heart rate may be a response to pain, excitement, hypovolemia, or endotoxemia. Bradycardia is rare but may be detected in foals with uroabdomen if they are hyperkalemic ([K+] greater than 5.5 mEq/dL). These foals are also prone to developing cardiac arrhythmias. Cardiac murmurs may be normal in foals up to 3 to 5 days old and are usually caused by blood flow through a patent ductus arteriosus. Such murmurs may sound like continuous machinery–type or systolic murmurs. Innocent flow murmurs can be heard in some foals, but these are restricted to the left heart base and are usually less than grade 2/6. Fever and anemia can also result in cardiac murmurs. The lungs should be ausculted on the right and left sides and over the trachea. Borborygmus heard within the thorax is normal because of the shape of the diaphragm and is not indicative of diaphragmatic hernia.

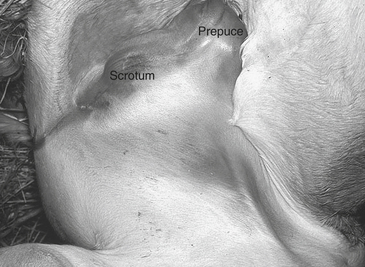

The abdomen can be ausculted, balloted, palpated, and percussed. Progressive borborygmus is produced by gas and fluid interfaces within the gastrointestinal tract. The presence of audible borborygmus is usually considered normal. However, foals with gastrointestinal obstruction will initially have borborygmus that may be increased followed by a period of decreased to absent intestinal sounds, indicating decreased gastrointestinal motility or ileus. Increased borborygmus may indicate enteritis. Percussing the abdomen and listening for a ping can detect gas distension of the cecum and colon. Palpation of the umbilicus and inguinal area is performed to identify hernias. Many reducible umbilical and inguinal hernias are found incidentally during the physical examination, but if pain is elicited during palpation or if the hernia is not reducible, surgery is usually indicated. In cases of inguinal hernia, emergency surgical correction is advised if the tunic is ruptured, small intestine is in the subcutaneous space, and there is medial thigh and preputial edema (Figure 192-1).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Differential diagnoses for neonatal foal colic include meconium retention (see Chapter 187, Meconium Impaction), enterocolitis (see Chapter 191, Inflammatory Bowel Diseases in Foals), uroabdomen and ruptured bladder, and congenital lesions.

Ruptured Bladder

Foals with ruptured bladder or urachal tear usually begin to develop clinical signs of uroabdomen by 24 to 72 hours of age. These foals “flag” their tails, are restless, and strain to urinate. Although most affected foals dribble urine, some may continue to pass a stream of urine. Foals with previous or ongoing septic umbilical structures are at risk for necrosis of the urachus, which can lead to uroabdomen. Foals with uroabdomen caused by a ruptured or torn ureter may show clinical signs later, from 4 to 7 days of age. There is no sex predilection, but these foals may have some history of trauma at birth, such as falling if parturition occurred with the mare standing. Uroabdomen is diagnosed based on ultrasonographic observation of anechoic free peritoneal fluid (Figure 192-2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree