Elizabeth J. Davidson

Evaluation of the Horse for Poor Performance

Poor performance is a common problem in horses of all breeds and athletic uses. There are many causes of poor performance, and comprehensive testing is often required for accurate diagnosis. Evaluation centers on obtaining an accurate history and performing a detailed clinical examination with the use of appropriate diagnostic tools as well as specialized techniques.

What is Performance?

The horse is an amazing athlete that is able to run, turn, and jump over a variety of surfaces while bearing the weight of a rider or pulling a driver. When a horse is evaluated for poor performance, considerations must be made for the type and demands of the competition. Successful racehorses must outperform fellow competitors by crossing the finish line first. In nonracing performance horses such as sport horses, athletic ability is more difficult to define. In these types of horses, performance is often subjectively judged and compared with other competitors. Judging points may be the elegance of a particular movement, or sheer jumping ability, for example. Although it is not necessary for the examining veterinarian to be an accomplished rider or trainer, it is helpful if he or she has a clear understanding of and is familiar with the discipline linked to the horse’s use. It is difficult to assess a “poor quality” extended trot without prior knowledge of what a good quality extended trot should look like. Regardless of the type of competition, for the horse to perform adequately, its athletic ability is dependent on coordinated movements and complex relations between many body systems.

Factors Limiting Performance

Peak performance requires all body systems to function at or close to their maximal capacity. For healthy horses, performance-limiting factors depend on the type of exercise engaged in. In racehorses, running at top speed is limited by oxygen transport. Any reduction in oxygen availability (e.g., such as would be caused by a decrease in laryngeal cross-sectional area secondary to recurrent laryngeal neuropathy) will diminish the performance capacity of the respiratory system, which in turn affects the rest of the body systems. However, if the performance does not require peak effort, impairments in physiologic functions may be tolerable. A dressage horse with recurrent laryngeal neuropathy, for example, may still be able to perform (although the associated abnormal respiratory noise may detract from its performance). It is important to understand the physiology during exercise for each breed and use so that the likely cause or causes of poor performance in a given individual horse can be determined.

Musculoskeletal injury is the most common cause of poor performance in horses. All types of horses are susceptible to lameness, and sooner or later most horses are affected by it. In the horse industry, more than $1 billion is lost every year to lameness, with the largest component of costs attributed to loss of use. The annual incidence of horse lameness in the United States is approximately 9 to 14 events per 100, and about one half of horse operations report 1 or more horses with lameness during the previous year. Boarding and training facilities are more likely to have lameness affect horses, compared with ranches or farms, breeding facilities, or personal-use stables. This difference is likely a result of the differences in exercise intensity horses are subject to and perhaps a greater awareness of lameness on the part of owners. Lameness accounts for approximately 8% of all equine losses annually.

The prevalence of respiratory disease in all types of competition horses is also high, and in many instances, airway disorders only arise during exercise. Upper airway obstructions and lower respiratory tract diseases are most common. Abnormalities of the cardiovascular system can also negatively affect performance by reducing cardiac output. It can be difficult to ascertain the impact of cardiac conditions on performance because many normally functioning horses have murmurs and dysrhythmias, most of which are physiologic in nature and have a negligible effect on performance.

Muscle strains, tears, and soreness are also common in the athletic horse. Exertional rhabdomyolysis occurs in approximately 3% of poorly performing horses, and subclinical myopathy occurs in as many as 15% of racehorses. Less common causes of poor performance include neurologic diseases. Overt incoordination or stumbling is easily recognized, but subtle weakness and mild ataxia may necessitate a more discerning clinical examination. Numerous other metabolic, endocrine, and electrolyte disturbances can also be a cause for loss of athletic ability.

Poor Performance Testing

When one or more body systems break down functionally and the horse is no longer able to perform up to its potential, testing is focused on the reason or reasons for the diminished ability. In some horses, the cause for the poor performance is obvious: a horse with severe musculoskeletal injury will be severely lame. However, in many instances, the horse has a subtle or gradual decline in performance and has few or no distinct abnormal clinical findings. Common complaints from riders, trainers, or owners may include trailing off at the end of competition, long recovery periods, or the observation that the horse is “just not right.” In these kinds of poorly performing horses, clinical signs may be subtle, intermittent, or only apparent during exercise.

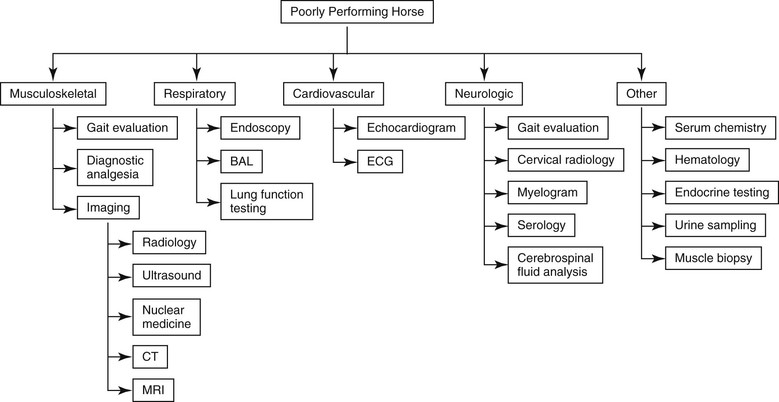

The fewer the possible factors that contribute to the poor performance, the more likely the testing will provide useful information. For example, in a racehorse that is making a loud, consistent, abnormal respiratory noise during exercise, endoscopy during exercise is very likely to reveal a definitive answer. However, taking into account the number and complexity of mechanisms that are all involved in a good performer, investigation of poor performance or loss of performance can be a substantial challenge. This is when real detective work begins for the examining veterinarian. It starts with obtaining a clear and accurate history, followed by a thorough physical examination. It may also involve numerous diagnostic tests, the expertise of multiple clinicians, and access to a good laboratory for cytologic and hematologic analysis (Figure 18-1).

The value of obtaining a thorough and accurate history cannot be overstated. This includes not only a detailed description of the presenting complaints, including duration, but also past and present performance history. Obtaining an accurate database requires excellent communication skills. By using open-ended questions, the examining veterinarian is more likely to get the correct information than by using closed-ended yes-or-no questions. For example, when the closed-ended question, “Do you give your horse any medications?” is asked, the client’s answer is almost always “No.” Rephrasing the question into an open-ended one such as, “How have you been managing your horse?” requires the client to provide more than one-word answers. The answers may come in the form of a list, a paragraph, or an essay, but in any event the “no medication” response is almost always a “yes” by the end of the conversation. This is no fault of the client, but is simply the result of a poorly asked question. Although they can be time-consuming, asking well-constructed questions and listening effectively to the responses is critical and can guide the veterinarian down the appropriate diagnostic pathway.

With many readily accessible imaging modalities, a detailed physical examination is often performed incompletely, circumvented, or avoided altogether. Although it is easier to charge the client for five radiographic images of the tarsus than for a 5-minute digital palpation of the limbs, there is tremendous diagnostic value in performing a physical examination. It starts with static observation. Visually obvious abnormalities such as joint swelling and muscle atrophy should be noted. This is also the time to make a mental note about the horse’s overall conformation. In particular, limb alignment, specifically malalignment, should be noted. There is some evidence that conformation abnormalities may be risk factors in lameness. This is also the time to observe weight distribution. A horse that constantly points a front toe is providing a good indication of heel pain in that foot. In addition to the musculoskeletal system, particular emphasis should also be placed on the respiratory and cardiovascular systems. However, any body system can affect performance, and thorough examination of the entire horse is recommended.

Because musculoskeletal injury is the most common cause for loss of performance, poor performance evaluation should include a thorough musculoskeletal examination. Although overt lameness is easily recognized and is an accepted cause of poor performance, mild or subtle lameness is often overlooked as a potential cause of decreased performance. Depending on the nature of the gait disorder, specific exercises (e.g., jumping or evaluation under tack) may also be necessary. As with any thorough lameness examination, diagnostic analgesia techniques (nerve and joint blocks) are also recommended to pinpoint the authentic source of pain. It must be borne in mind that some good performers succeed despite having musculoskeletal pain: an elite show jumper with chronic foot pain may limp in the parking lot but run and jump fault free. In any instance, identification of musculoskeletal pain is important, but equally important is its impact on the performance.

Numerous imaging tools assist the veterinary diagnostician in identification of a plethora of possible types of musculoskeletal injuries. Radiography and ultrasonography are routinely used not only for the evaluation of poor performance but also for evaluation of good performers (e.g., such as during prepurchase examinations). Nuclear scintigraphy remains the gold standard for early recognition of a stress fracture before catastrophic injury (see Chapter 202). Identification of these and other stress-related bone injuries is critical in the poor performer because affected horses often have inconsistent, subtle, or multiple-limb lameness. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are increasingly more available to the equine diagnostician and are especially useful for evaluating foot and subchondral bone diseases.

Respiratory impairments are also common in poor performers. Detection of disease can be complicated by the absence of clinical signs such as cough or nasal discharge, and the ability to predict exercising upper airway function must often be based on resting endoscopic findings. Abnormal respiratory noise during exercise is a common clinical clue associated with upper airway obstruction, but as many as 30% of horses with intermittent dorsal displacement of the soft palate do not make noise. Therefore endoscopy during exercise is particularly useful and has facilitated the diagnosis of a sundry of performance-limiting upper airway obstructions (see Chapters 51, 54, and 55). In the show horse, upper airway obstruction may be tolerated despite the presence of noise. Abnormal respiratory noise or exercise intolerance can be exacerbated by head and neck flexion, a position required or desired for certain disciplines, movements, and gaits of showhorses. Lower airway inflammation or disease, another important cause of reduced athletic ability, can be ascertained with lung function testing such as forced oscillometry and bronchoalveolar fluid cytology. Subclinical lung disease is common in all types of performance horses and can be particularly challenging to diagnose.

The incidence of cardiac murmurs in performance horses is also high, with mitral and tricuspid valvular regurgitation being the most common, although most murmurs are of minimal consequence to performance (see Chapter 122). Arrhythmias are also common, and some dysrhythmias, such as atrial fibrillation, have been associated with poor performance secondary to decreased cardiac output (see Chapter 121). Telemetric electrocardiography (ECG) assessment in the horse during either overground or treadmill exercise is relatively easy to perform and is usually diagnostic. Postexercise stress echocardiography performed immediately after peak exercise can be useful for assessment of myocardial function.

In horses with suspected neurologic diseases, additional gait and posture evaluations are indicated. Also included are observations of mental status, head position, vision, and muscle symmetry. Ancillary diagnostic aids include cerebrospinal fluid analysis, cervical radiology, myelogram, and serology. A multitude of additional tests are recommended for horses with suspected endocrine, metabolic, or electrolyte abnormalities.