Courtesy of A.T. Fischer, Jr. and Chino Valley Equine Hospital.

Most horses presenting to the author’s hospital will be initially evaluated during a routine colic workup. This colic workup includes physical examination; routine blood work (CBC with fibrinogen and a chemistry panel); abdominal radiographs for detecting foreign bodies, sand accumulation in the colon, or enteroliths (Figure 9.2); abdominal ultrasound for potential small intestinal abnormalities (Figure 9.3); gastroscopy; rectal examination; and abdominal fluid analysis. In most cases, the initial workup leads to a differential diagnosis with either medical or surgical treatment or a combination of the two.

Figure 9.2 Horse with large enterolith seen on abdominal radiographs.

Courtesy of A.T. Fischer, Jr. and Chino Valley Equine Hospital.

Figure 9.3 Horse with distended loops of small intestine and no evidence of motility.

Courtesy of A.T. Fischer, Jr. and Chino Valley Equine Hospital.

Laparoscopic evaluation of the equine patient with colic is most commonly used in horses with a history of chronic colic or a low grade of pain or weight loss. All of the horses that are being evaluated for chronic/low grade pain or weight loss will have had an extensive workup.

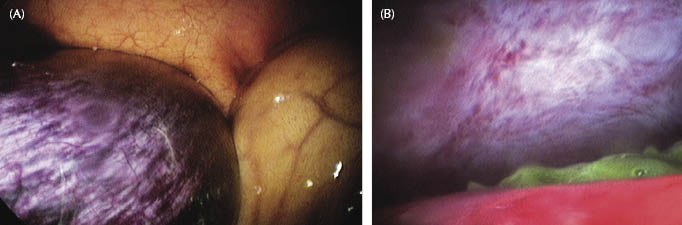

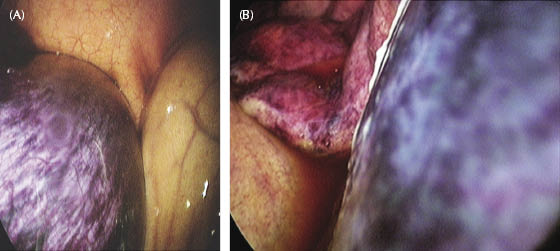

In horses with acute signs of abdominal pain, laparoscopy is not used as frequently because of the increased risk of a distended viscus (gas or feed material). In the acute colic case, laparoscopy is most commonly used in horses with no clear indication for either surgery or euthanasia, and in cases in which clients are unable to give permission for an exploratory celiotomy. Abdominal laparoscopy is also used to confirm a diagnosis that would require a colic surgery as treatment (Figure 9.4A) or to confirm a localized rupture of a viscus (Figure 9.4B).

Figure 9.4 (A) Horse with a 2-in. section of nonviable small intestine seen in the caudal abdomen with the laparoscope inserted in the right paralumbar fossa. (B) Laparoscopic view of a localized rupture of the large colon. The green material is digested alfalfa hay.

Courtesy of A.T. Fischer, Jr. and Chino Valley Equine Hospital.

Different causes of acute signs of colic, chronic signs of colic, and weight loss will be discussed, and cases will be provided with pictures.

Laparoscopy for Acute Signs of Abdominal Pain

Postcastration Bleeding

The horse has been previously castrated and is bleeding from the scrotum or into the abdominal cavity. In order to detect intra-abdominal bleeding, abdominal ultrasonography needs to be performed and reveal free blood in the abdominal cavity (Figure 9.5).

Figure 9.5 Horse has been previously castrated and developed mild to moderate signs of abdominal pain. Abdominal ultrasonography reveals free intra-abdominal blood.

Courtesy of A.T. Fischer, Jr. and Chino Valley Equine Hospital.

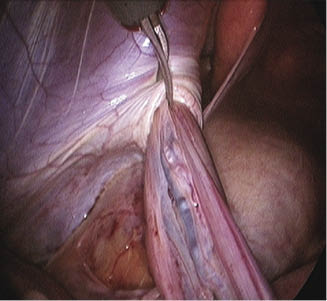

If it is indicated, either a standing flank laparoscopy can be attempted in order to detect the source of the hemorrhage or the horse can be placed in a Trendelenburg position and the caudal abdomen examined. In either situation, a moderate amount of hemorrhage is noted in the caudal abdomen (Figure 9.6). A standing flank laparoscopy may be more difficult to perform in this situation because the intra-abdominal blood may obscure the view of the inguinal rings and may make it more difficult to locate the bleeding vessel. As a result of the intra-abdominal blood, the end of the laparoscope may also be constantly covered with blood, which will make the evaluation of the internal inguinal ring more difficult.

Figure 9.6 Laparoscopic view of free intra-abdominal blood secondary to castration and bleeding from the testicular artery.

Courtesy of A.T. Fischer, Jr. and Chino Valley Equine Hospital.

Evaluating a horse for postcastration bleeding under general anesthesia has several advantages. The horse is placed in Trendelenburg position, which will give the surgeon an unobstructed view of the inguinal region (the intra-abdominal blood will be displaced in the cranial abdomen). As a result of not having intra-abdominal blood obstructing the view, the bleeding vessel will be easier to identify. The other advantage over a standing laparoscopy is that any scrotal or intrascrotal bleeders could be more easily identified and ligated. One major disadvantage of evaluating a horse under general anesthesia that is bleeding in the abdomen after a castration could be that the horse may show signs of cardiovascular compromise, which would make general anesthesia more difficult.

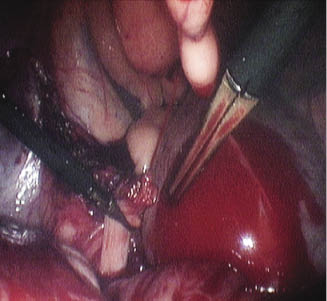

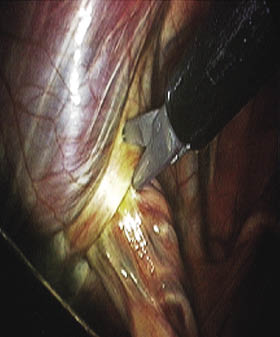

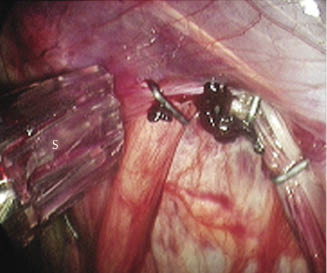

After the source of the intra-abdominal bleeding is identified (possibly the testicular artery), it should be ligated with the placement of a ligaclip or a ligaloop. A cautery unit may also be used to stop the bleeding (Figure 9.7).

Figure 9.7 Laparoscopic view of a horse after castration showing a moderate amount of colic signs. Intra-abdominal ligation of a bleeding vessel after castration.

Courtesy of A.T. Fischer, Jr. and Chino Valley Equine Hospital.

Postcastration Evisceration

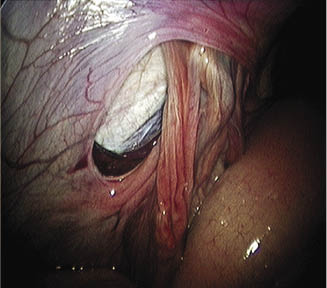

The horse has been previously castrated and a section of the intestine (usually the small intestine) is visible in the scrotal incision. Should this situation occur at a referral hospital (after routine castration), the horse would be immediately reanesthetized in order to decrease the level of contamination. Most of the cases are encountered on an ambulatory basis, and the referring veterinarian needs to administer emergency care (stabilization of the patient with temporary closure of the scrotal incision). Once the horse arrives at the referral hospital, the horse will be evaluated (physical examination, routine blood work, abdominal ultrasound, and preparation for general anesthesia). Depending on the time of duration and the level of contamination to the herniated intestine, the herniated intestine may not need to be resected. Once the horse is adequately evaluated at a referral hospital, the horse is taken to general anesthesia and placed in a Trendelenburg position. A 30° laparoscope is placed inside the abdominal cavity and the inguinal rings are evaluated. One of the internal inguinal rings will have been stretched and will reveal a section of herniated intestine (Figure 9.8).

Figure 9.8 The horse had been previously castrated and eviscerated a section of small intestine. Laparoscopic view of a herniated small intestine through the internal inguinal ring.

Courtesy of A.T. Fischer, Jr. and Chino Valley Equine Hospital.

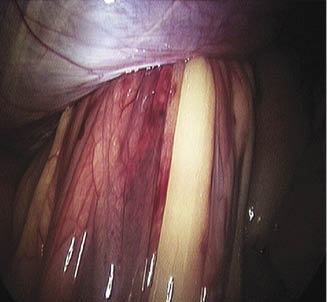

Two instrument portals will be created and two nontraumatic forceps are introduced into the abdominal cavity. Thereafter, the herniated intestine will be reduced in a hand-over-hand motion (Figure 9.9).

Figure 9.9 Laparoscopic view of a herniated intestine through the inguinal ring being reduced with two atraumatic forceps.

Permission from Equine Diagnostic and Surgical Laparoscopy, A.T. Fischer, Jr., Copyright Saunders (2001). Courtesy of A.T. Fischer, Jr. and Chino Valley Equine Hospital.

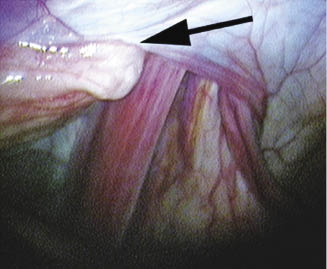

In some occasions, the vaginal ring is too tight and needs to be sectioned with laparoscopic scissors before the herniated intestines can be reduced (Figures 9.10 and 9.11).

Figure 9.10 Laparoscopic view of the caudal abdomen: sectioning of vaginal ring with laparoscopic scissors in order to reduce the herniated small intestine.

Courtesy of A.T. Fischer, Jr. and Chino Valley Equine Hospital.

Figure 9.11 View of sectioned vaginal ring (arrow) in order to reduce the herniated small intestine.

Permission from Equine Diagnostic and Surgical Laparoscopy, A.T. Fischer, Jr., Copyright Saunders (2001). Courtesy of A.T. Fischer, Jr. and Chino Valley Equine Hospital.

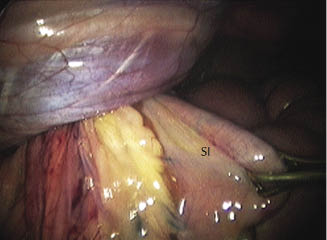

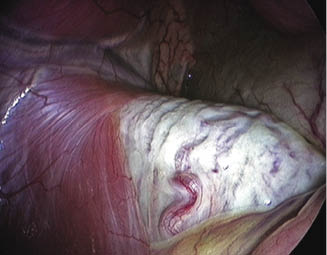

Once the previously herniated small intestine is reduced, it is evaluated for its viability (serosal surface, mesentery, and mesenteric blood vessels). The entire small intestine should be evaluated (Figure 9.12).

Figure 9.12 Laparoscopic evaluation of the previously herniated small intestine. The small intestine is evaluated for its viability.

Courtesy of A.T. Fischer, Jr. and Chino Valley Equine Hospital.

If the small intestine does not appear to be viable, the laparoscopic procedure is converted to an open ventral midline celiotomy with small intestinal resection, anastomosis, and routine closure of the inguinal ring from the scrotal side.

Scrotal Hernia in Adults

A horse presents with acute and sometimes moderate to severe signs of abdominal pain. A physical examination of the horse will not reveal any specific signs, but one of the testicles will be larger compared with the other. Abdominal ultrasonography should be performed and may reveal distended loops of small intestine with decreased motility. Abdominal palpation per rectum should be performed and will reveal an incarcerated small intestine traveling through one of the inguinal rings. A scrotal ultrasound may reveal a section of edematous small intestine.

The horse should be prepared for surgery (general anesthesia) and placed in Trendelenburg position. The enlarged scrotal region (Figure 9.13A) and the ventral abdomen both need to be prepared for aseptic surgery. The laparoscope is placed in the abdominal cavity and the inguinal rings are evaluated (Figure 9.13B).

Figure 9.13 (A) Horse with small intestinal scrotal hernia. The horse is under general anesthesia and is being prepared for abdominal laparoscopy. (B) Intra-abdominal view of inguinal ring with herniated small intestine in a stallion.

Courtesy of A.T. Fischer, Jr. and Chino Valley Equine Hospital.

Inspection of the inguinal rings reveals a section of herniated small intestine. Two atraumatic forceps are placed inside the abdominal cavity in order to reduce the small intestine in a “hand-over-hand” motion (Figure 9.14).

Figure 9.14 Reduction of the herniated small intestine (jejunum) in a stallion with atraumatic forceps.

Courtesy of A.T. Fischer, Jr. and Chino Valley Equine Hospital.

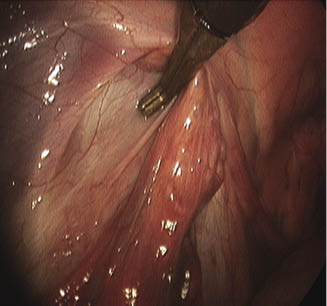

In some cases, the herniated intestine is very edematous and fluid filled and cannot be reduced. In order to aid reduction of the small intestine, the vaginal ring will need to be sectioned with laparoscopic scissors (Figure 9.15). Once the small intestine is reduced, it will need to be evaluated for its viability and a possible need for resection. If the small intestine does not appear to be viable, a small intestinal resection and anastomosis needs to be performed via a ventral midline laparatomy.

Figure 9.15 Sectioning of the vaginal ring with laparoscopic scissors in order to aid reduction of the herniated small intestine.

Permission from Equine Diagnostic and Surgical Laparoscopy, A.T. Fischer, Jr., Copyright Saunders (2001). Courtesy of A.T. Fischer, Jr. and Chino Valley Equine Hospital.

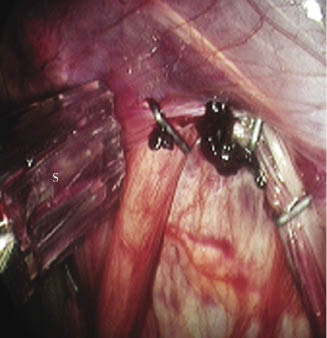

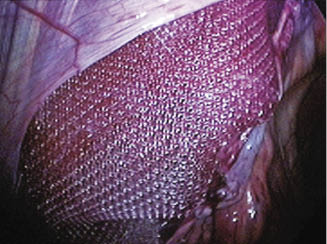

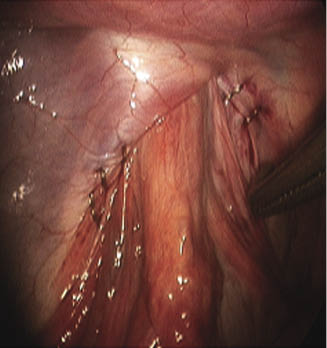

The testicle and its associated blood supply on the herniated side need to be evaluated for its viability. If the testicle on the herniated side is viable, the inguinal ring can be closed with staples or a mesh (Figures 9.16 and 9.17).

Figure 9.16 Staple closure of the internal inguinal ring in order to preserve the vascular supply to the testicle.

Permission from Equine Diagnostic and Surgical Laparoscopy, A.T. Fischer, Jr., Copyright Saunders (2001). Courtesy of A.T. Fischer, Jr. and Chino Valley Equine Hospital.

Figure 9.17 Secure mesh closure of the internal inguinal ring in order to preserve the spermatic cord and vascular supply to the testicle after the previously herniated small intestine was reduced.

Permission from Equine Diagnostic and Surgical Laparoscopy, A.T. Fischer, Jr., Copyright Saunders (2001). Courtesy of A.T. Fischer, Jr. and Chino Valley Equine Hospital.

If the testicle is not viable, a routine castration with inguinal ring closure is performed from the scrotal side.

Scrotal Hernia in Foals

In foals, hernias can be either direct or indirect. In direct hernias, the vaginal tunic is usually torn (Figure 9.18). The foal is placed under general anesthesia, and the small intestine is reduced either with an open ventral midline procedure or under laparoscopic guidance. Thereafter, a routine (suture) closure of the inguinal ring is performed from the scrotal side.

Figure 9.18 Laparoscopic intra-abdominal view of a herniated small intestine with torn vaginal tunic.

Courtesy of A.T. Fischer, Jr. and Chino Valley Equine Hospital.

Indirect scrotal hernias in a foal are more common, and the small intestine is herniated through the vaginal and internal inguinal rings (Figure 9.19). The vaginal ring typically does not need to be sectioned in order to aid reduction of the small intestine. The herniated small intestine is carefully reduced using atraumatic laparoscopic forceps (Figure 9.19). Once the small intestine is reduced, it is inspected for viability.

Figure 9.19 Laparoscopic intra-abdominal view of a herniated small intestine through the internal inguinal ring into the scrotum.

Courtesy of A.T. Fischer, Jr. and Chino Valley Equine Hospital.

As a result of the large size of the inguinal ring, typically the testicle moves freely between the abdominal cavity and the scrotal region (Figure 9.20).

Figure 9.20 Intra-abdominal view of a testicle located in the vaginal/inguinal ring. The testicle can be completely pulled into the abdomen, similar to a cryptorchid castration technique.

Permission from Equine Diagnostic and Surgical Laparoscopy, A.T. Fischer, Jr., Copyright Saunders (2001). Courtesy of A.T. Fischer, Jr. and Chino Valley Equine Hospital.

If an owner is amenable to early castration, a non-testicle-sparing technique is advocated. The testicle is pulled into the abdominal cavity and a routine intra-abdominal castration technique is used (similar to a cryptorchid castration technique).

After routine intra-abdominal castration, the vaginal ring is evaluated for subsequent staple closure (Figure 9.21).

Figure 9.21 View of the internal inguinal ring prior to staple closure.

Courtesy of A.T. Fischer, Jr. and Chino Valley Equine Hospital.

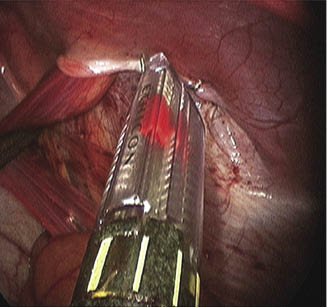

Multiple small individual endostaplers are used to close and secure the vaginal ring and inguinal ring completely (Figure 9.22).

Figure 9.22 View of the internal inguinal ring being closed with an endostapler.

Permission from Equine Diagnostic and Surgical Laparoscopy, A.T. Fischer, Jr., Copyright Saunders (2001). Courtesy of A.T. Fischer, Jr. and Chino Valley Equine Hospital.

Subsequent peritoneal and surrounding soft tissue swelling in the area assists to prevent postoperative herniation.

If an owner does not agree to an early castration technique, the testicle is pushed into the scrotum and a testicle-sparing technique is used (Figures 9.23 and 9.24)

Figure 9.23 Staple closure of the internal inguinal ring in order to prevent reherniation with spermatic cord and testicular blood vessels being spared.

Permission from Equine Diagnostic and Surgical Laparoscopy, A.T. Fischer, Jr., Copyright Saunders (2001). Courtesy of A.T. Fischer, Jr. and Chino Valley Equine Hospital.

Figure 9.24 Staple closure of the internal inguinal ring in order to prevent reherniation with spermatic cord and testicular blood vessels being spared.

Permission from Equine Diagnostic and Surgical Laparoscopy, A.T. Fischer, Jr., Copyright Saunders (2001). Courtesy of A.T. Fischer, Jr. and Chino Valley Equine Hospital.

The inguinal ring is closed with staples, allowing for the passage of the spermatic cord and vessels.

Omental Herniation into the Scrotum (After Previous Castration)

Once the horse is evaluated for signs of abdominal pain and the decision for laparoscopic surgery is made, the horse is placed in Trendelenburg position and the caudal abdomen is evaluated. Examination of the inguinal ring reveals a herniated omentum (Figure 9.25) through the internal inguinal ring into the scrotum.

Figure 9.25 Herniated omentum (arrow) (left side of the inguinal ring) through the internal inguinal ring after previous routine castration.

Courtesy of A.T. Fischer, Jr. and Chino Valley Equine Hospital.

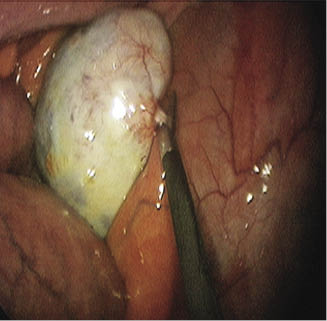

The omentum is either ligated or transected with the help of electrocautery (Figure 9.26). The sectioned omentum is then removed via the scrotum (previous castration site).

Figure 9.26 Laparoscopic view of transected omentum after the omentum had herniated through the internal inguinal ring. The omentum can either be ligated or transected with the help of an electrocautery unit.

Courtesy of A.T. Fischer, Jr. and Chino Valley Equine Hospital.

Thereafter, a staple closure of the vaginal ring/internal inguinal ring using endostaples is performed or routine suture closure from the scrotal approach is performed.

Small Intestine

The horse is evaluated at a referral hospital for previous signs of colic. A complete colic workup is performed and abdominal ultrasonography is suspicious for a possible strangulation obstruction of the small intestine. Abdominal palpation per rectum is within normal limits and the horse does not appear to be painful at the time of the initial examination and several hours after presentation. If the horse clinically deteriorates but still does not warrant an exploratory celiotomy or an owner does not consent to an exploratory, a standing flank laparoscopy is indicated. A standing flank laparoscopy allows for a direct evaluation of the abdominal structures. Laparoscopic evaluation of the abdominal cavity may reveal an increased amount of abdominal fluid and different stages of small intestinal compromise. The small intestine may appear to be distended and bruised but still viable (Figure 9.27).

Figure 9.27 Laparoscopic view of a bruised but viable section of the small intestine. The serosa of the small intestine has petechial hemorrhage.

Courtesy of A.T. Fischer, Jr. and Chino Valley Equine Hospital.

The small intestine may be severely bruised and the bruising will lead to secondary nonviability of the affected sections of small intestine (Figure 9.28), or the small intestine may be nonviable and needing resection (Figure 9.29).

Figure 9.28 Severe bruising of a section of the small intestine leading to it being nonviable. The horse had a strangulation obstruction of the small intestine (lipoma).

Courtesy of A.T. Fischer, Jr. and Chino Valley Equine Hospital.

Figure 9.29 (A) Section of small intestine that is nonviable after a strangulation obstruction. The small intestinal serosa has “turned purple.” (B) Section of compromised small intestine secondary to a strangulation obstruction—rent in the omentum.

Permission from Equine Diagnostic and Surgical Laparoscopy, A.T. Fischer, Jr., Copyright Saunders (2001). Courtesy of A.T. Fischer, Jr. and Chino Valley Equine Hospital.

If the small intestine appears compromised, the information can be relayed to the owner and further treatment options can be discussed (euthanasia or exploratory celiotomy with small intestinal resection and anastomosis).

Standing laparoscopic evaluation of the abdominal cavity may reveal the primary cause of the signs of colic. The following case revealed a lipoma around the small intestine (Figure 9.30) not causing a secondary compromise of the intestine or the associated mesenteric blood supply. The stalk of the lipoma had caused signs similar to a simple small intestinal obstruction (Figure 9.30).

Figure 9.30 Evaluation of the abdominal cavity revealed an obstruction of the small intestine. Laparoscopic view of a lipoma around the small intestine not causing intestinal compromise. The stalk is being sectioned with laparoscopic scissors.

Courtesy of A.T. Fischer, Jr. and Chino Valley Equine Hospital.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree