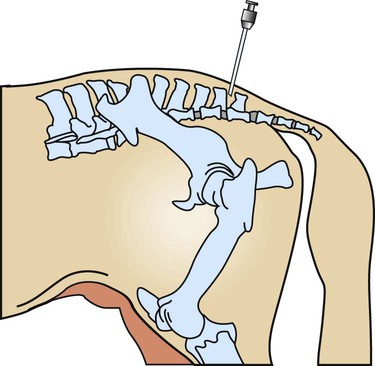

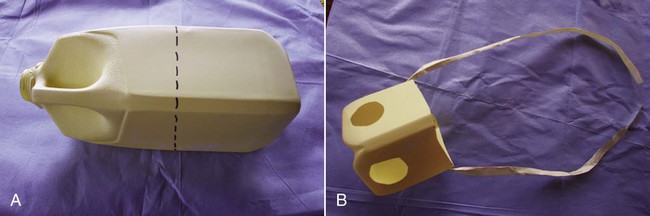

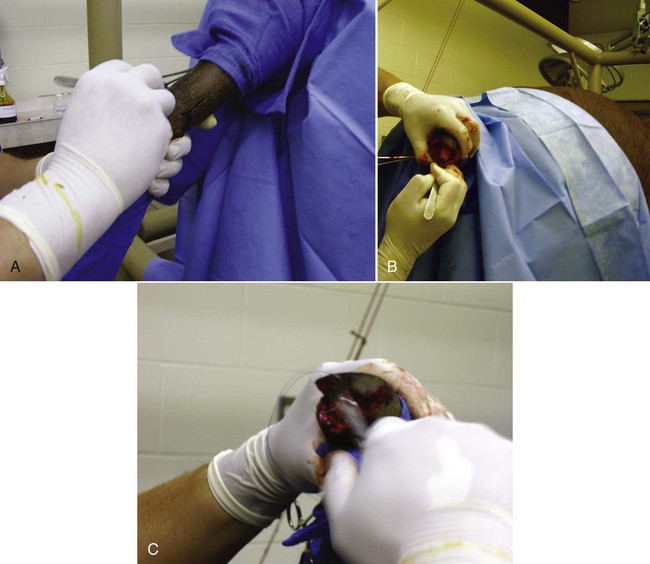

When you have completed this chapter, you will be able to • Understand the basic differences between standing surgical procedures and general anesthesia procedures • Prepare a patient for surgery • Assist with or perform induction and maintenance of anesthesia • Provide anesthetic monitoring • Manage the patient during recovery and immediate postoperative periods • Understand the basic risks and possible complications associated with anesthesia and surgery, and implement preventative measures when indicated The availability of surgical procedures depends on the following considerations: • Availability of surgical facilities • Expertise of available surgeons • Ability to provide aftercare and follow-up Surgical procedures can be divided into two major categories: Criteria and indications for standing surgery include the following: • The surgical technique must be one that is safe to perform on a standing horse. This implies safety for the horse, the surgeon and other personnel, and the equipment. • Because the risks of general anesthesia are avoided, standing surgery may be beneficial for sick, debilitated, or elderly patients. • The risks associated with recumbency under anesthesia (such as compartment syndrome) are avoided; therefore, large or heavily muscled horses, such as draft breeds, should undergo standing procedures whenever possible. • If the patient has undergone extreme stress or trauma, avoiding general anesthesia may be better for the patient. • If the patient has a history of problems under general anesthesia or has experience a difficult recovery, standing surgery may be preferable. • Usually standing procedures are less expensive than comparable general anesthetic procedures. Fewer drugs, less patient monitoring, and fewer staff members are generally required, all of which reduces costs. Standing surgery has drawbacks, however. Surgeon comfort is often compromised, especially if operating on the lower legs (Fig. 8-1). The surgeon’s visualization of the surgical field is often compromised because of the inability to use retractors and often poor lighting. It is very difficult to drape and maintain a sterile surgical field and to control contamination of instruments, especially under farm conditions (Fig. 8-2). Finally, because the patient is awake, the patient can move, presenting a danger to itself, personnel, and equipment. Even with heavy sedation and physical restraint, the possibility of motion must always be considered and precautions taken. Restraint of the patient depends on the location of the procedure, duration of the procedure, “pain factor” of the procedure, temperament of the horse, facilities, and skill and number of available personnel. Physical restraint may range from a halter and lead shank to mechanical devices such as twitches and ropes. Chemical restraint (sedation or tranquilization) is often used; sometimes heavy sedation must be used (Fig. 8-3). Every procedure and patient is different; therefore, restraint must be tailored for the situation. The pharmacology and effects of drugs used for restraint and analgesia are thoroughly discussed in numerous excellent references on anesthesia and pharmacology. The clinical effects of the most commonly used chemical restraining agents are listed in Box 8-1. Local anesthesia may be applied in several ways. Three classes of drugs can be used for caudal epidurals: 1. Local anesthetics block not only sensory fibers but also motor fibers and sympathetic fibers. Loss of motor control can cause ataxia and even collapse of the hindlimbs; this is a rare occurrence but can be disastrous if it does occur. 2. Alpha-2 agonists selectively block sensory fibers, with minimal effects on hindlimb function. 3. Opioids selectively block sensory fibers, with minimal effects on hind limb function. Caudal epidural anesthesia is easily performed on large animals. The site of injection is between the first and second coccygeal vertebrae, on the dorsal midline (Fig. 8-4). An estimate of this location is made by moving the tail up and down while palpating for the first movable intercoccygeal space caudal to the sacrum. The patient should be restrained, and personnel should stand to the side of the patient to avoid being kicked. Foals are allowed to nurse until approximately 30 to 60 minutes before induction of general anesthesia. This allows time for the stomach to empty, which is important because foals, unlike adults, may regurgitate after induction. If the foal is eating solid food, it should be removed for 3 to 4 hours before induction. To prevent nursing the mare, a muzzle must be used on the foal. Foal muzzles can be purchased or made from half-gallon milk cartons by cutting the carton in half. Two nostril openings are made, and the muzzle is secured behind the foal’s ears with gauze or twine straps (Fig. 8-5). Occasionally it may be desirable to leave horseshoes on, especially if they are being used to correct or treat a medical condition. In such cases, the hooves should still be cleaned and some type of protective boot or hoof bandage placed over the shod hoof before anesthetic induction (Fig. 8-6). General considerations for induction and maintenance of general anesthesia include the following. The four clinically significant muscle compartments are the • Minimize anesthetic time: The incidence of compartment syndrome increases with anesthesia time, especially in procedures lasting longer than 1 hour. As much prepping of the patient and setup of the surgical area as possible should be done before induction. • Maintain anesthesia only as deeply as necessary: Blood pressure drops as the depth of anesthesia increases, increasing the risk to the patient. • Use adequate padding: Facilities vary with regard to the type of padding used, but thick foam mattresses (15–20 cm thick), conventional mattresses, air mattresses, and waterbed mattresses can be used successfully (Fig. 8-7). • Position the patient properly: • Lateral recumbency: Place the forelimbs in a “staggered” position by pulling the lower forelimb forward (cranially) to rotate the shoulder girdle. This position decreases the body weight pressing down on the triceps muscle. The hindlimbs are not staggered. Elevate the upper limbs (both forelimb and hindlimb) to a horizontal position, parallel to the ground. Do not elevate the upper limbs above this level (Fig. 8-8). Protect the masseter muscle by removing or loosening the halter after induction and padding the area supporting the head.

Equine Surgical Procedures

Equine Surgery and Anesthesia

Standing Surgery

Preparation for Standing Surgery

Control of Pain

Epidural Anesthesia

General Anesthesia

Preanesthetic Preparation

Ventilation Problems under General Anesthesia

Preventing Contamination of the Surgical Room

Induction and Maintenance of General Anesthesia

Prevent Compartment Syndrome

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

-inch needle (large patients may require an 18-ga ×

-inch needle (large patients may require an 18-ga ×  -inch spinal needle) at a 90-degree angle to the skin and advances it into the epidural space. Anesthetic solution is injected with a sterile syringe. Because sterile injection technique is required, the anesthetic solution should be taken from a new, previously unopened container. Sometimes the needle is left in place in case the patient needs more anesthetic later in the procedure. The needle should not be withdrawn until the clinician approves because bleeding and swelling (after removing the needle) can make repeating the epidural procedure difficult. Complications are unusual, and aftercare involves imply cleaning the area and applying an antibiotic or antimicrobial ointment to the puncture site.

-inch spinal needle) at a 90-degree angle to the skin and advances it into the epidural space. Anesthetic solution is injected with a sterile syringe. Because sterile injection technique is required, the anesthetic solution should be taken from a new, previously unopened container. Sometimes the needle is left in place in case the patient needs more anesthetic later in the procedure. The needle should not be withdrawn until the clinician approves because bleeding and swelling (after removing the needle) can make repeating the epidural procedure difficult. Complications are unusual, and aftercare involves imply cleaning the area and applying an antibiotic or antimicrobial ointment to the puncture site.