Chapter 16 EQUINE EMBRYO TRANSFER

An increasing amount of work has been done in the area of embryo transfer (ET) since it was first reported in 1972 by Oguri and Tsutsumi.1 Despite the efforts of many clinicians and laboratories working in the equine field, progress has been slow compared with that accomplished in bovine, ovine, and swine. Perhaps the major reason why equine ET has lagged behind is the lack of interest by most breed associations in registering foals born by ET. More recently some associations have become more flexible and accept ET as an alternative to regular breeding. Although there are products in the market that can be used to induce multiple ovulations, the results obtained with such products have been inconsistent and not yet very practical, which still renders ET inefficient in the horse.2 Since the development of blood typing and DNA parentage verification, parentage errors or frauds can be easily avoided. Even so, many breed registries either do not accept registration of offspring produced by ET or have restrictions on the number of registerable ET foals produced from one mare during a breeding season.

At our clinic, ETs are performed primarily from polo pony mares. In addition, Warmblood, Quarter Horse, Arabian, and Peruvian Paso mares are commonly used as embryo donors. The Argentinian Polo Pony Breeders Association (AACCPP) has no restrictions on the number of foals that can be registered every season. Since the first ET in polo ponies was performed in 1989,3 there has been a significant number of foals produced using this technology. During the 2007-2008 ET season, approximately 4000 pregnancies were produced by ET in Argentina. It is common for a donor mare to produce four to five pregnancies in the remainder of a breeding season after the polo season. At Doña Pilar, up to 13 foals have been produced from the same mare during one breeding season.

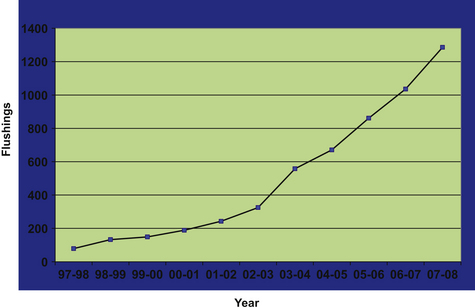

This chapter describes the practical aspects related to a large-scale commercial ET program in Argentina. In addition, some of the factors that have been determined to influence the success of the program are discussed. Fig. 16-1 shows the distribution from 10,256 uterine lavages for embryo collection performed on 2174 donor mares over the last 11 years. These mares were bred by artificial insemination to one or more of 160 stallions. This graph is a reference for the discussion of several factors affecting the overall success of ET.

APPLICATIONS OF EMBRYO TRANSFER IN THE EQUINE INDUSTRY

Young Mares

Frequently, a 2-year-old mare that becomes pregnant fails to carry a foal to term. Immaturity, stress, abortion, or embryonic loss have been implicated.4 Two-year-old mares, particularly late in the spring, are good embryo donors, provided that they are of a similar body size compared with mature mares.5

Old Subfertile Mares

Old mares with uterine conditions such as periglandular fibrosis, endometrosis,6 or endometritis7 can become pregnant, but early embryonic death (EED) or abortion may occur. In such cases, transfer of the embryo to a healthy uterus increases the chances of obtaining offspring from that mare.8,9 At Dona Pilar, many old subfertile mares consistently produce several foals every year.10

Mares in Competition

ET allows pregnancies in mares without interfering with their athletic careers. By obtaining embryos from competition mares, the time interval to the next generation can be shortened for a mare, which otherwise would not be able to deliver offspring until later in her life. Through ET, mares can produce several foals each breeding season, even though they are competing.4,11

Some studies have indicated that exercising can be detrimental to embryo recovery rates and can increase the incidence of morphologic abnormalities, which can be related to thermal stress.11 We believe that this depends on the conditions of the exercising. Embryo recovery rate and embryo morphology rate was not affected in competing Warmbloods in Germany12 or in performance polo ponies in England.13

PROCESS INVOLVED IN AN EMBRYO TRANSFER PROGRAM

Selection and Management of Embryo Donors

Breeding Soundness Evaluation

If a fertility problem is detected, appropriate therapy is instituted. The most common therapy performed at our clinic is a uterine lavage, using large volumes of prewarmed sterile saline14 on mares with clinical signs of endometritis. Several lavages are performed until the effluent is clear; then 20 IU of oxytocin is given intravenously to induce uterine contractions. The treatment is repeated several times until signs of endometritis have disappeared. Intrauterine infusion of antibiotics, which are selected based on culture and sensitivity, is sometimes performed.15 In some cases, response to therapy is evaluated by an endometrial biopsy and graded according to Kenney’s grading system.6

Selection and Management of Recipients

One of the most critical aspects that determines the success of an ET program is the selection, management, and quality of the recipient mares. Good recipient mares should meet all of the following requirements: (1) good health and body condition, (2) easy to handle and halter broken, (3) body size similar to that of the embryo donor, (4) 4–10 years of age, (5) sound breeding condition and a uterine biopsy grade l or IIA according to Kenney,6 (6) good estrus displayed when teased, and (7) regular cycling.

We prefer mares that have foaled normally at least once and that have shown good ability to nurse the foal. Although primiparous mares can be used, it is important to advise the owner of the embryo that the mare may need more attention at the time of foaling and that foals can be of smaller size at birth. Mean placental parameters and foal birthweights were shown to be lower in primiparous mares when compared with mares on the second or subsequent parities. The primiparous mares showed a significant reduction in the areas of microcotyledons compared with mares in their second or subsequent parities.16

Careful attention is given to the size of the recipients. Polish workers have shown the effect of the size of the recipient on the size of the offspring.17 In this study, embryos obtained from Polish pony mares (380–400 kg) and transferred into large recipients (560–780 kg) developed into foals that were larger and heavier than their siblings born to the genetic mothers. Embryo transfer into larger mares also resulted in foals that grew faster during the nursing period.

Lagneaux and Palmer18 in 1989 suggested that the uterus of a pony mare responds differently from that of a large mare to the cervical stimulation induced during non-surgical ET performed on day 7 after ovulation. The investigators demonstrated that prostaglandin release resulting from mechanical stimulation or endometritis induces luteolysis more frequently in pony mares than in large Selle-Francaise mares. Nine embryos transferred transcervically to pony mares resulted in no pregnancies, whereas nine embryos transferred to Selle-Francaise mares yielded four pregnancies.18

Synchrony between Donor and Recipient Mares

One of the most time-consuming activities in an ET center is related to the examination of donors and recipients to determine ovulation dates and degree of synchrony between them. This examination is routinely performed by transrectal palpation19 and ultrasonography20 of the ovarian structures. Serum progesterone levels are also used for this purpose.21,22

Several authors have shown that pregnancy rates are similar when transferring the embryos to recipient mares that have ovulated 24 hours before (−24) and up to 72 hours after (+72) donor ovulation.23–30 However, a retrospective analysis of 544 embryos transferred non-surgically to mares that ovulated within −24, 0, + 24, and +48 hours of the donor indicated that pregnancy rates were similar for 0, +24, and +48 hours (58.4%, 62.3%, and 62.3%, respectively) but were lower (50%) for the mares that ovulated 24 hours before the donor. When a smaller number of embryos were transferred to recipients ovulating 72 hours after the donor, pregnancy rates were further enhanced (83.8%). Based on these data, we prefer recipients to ovulate on the same day or after the donor. Furthermore, because it appears that pregnancy rates are not affected by day of ovulation, as long as recipients ovulate after the donor, we examine recipients every other day or every 2 days, based on recipient demand.

The method used for synchronization depends on the number of donors and recipients involved in the program. If there is a large number of recipients, synchronization may be performed by administration of a luteolytic dose of PGF2α or an analogue given to one or two recipients l or 2 days after administration to the donor. In large programs recipient availability can sometimes be a limitation. The optimal ratio should not be lower than 1.2 recipients per donor. Ovulation usually occurs 6–8 days after treatment if prostaglandin is given between days 6 and 9 of the cycle. However, response to treatment and time to ovulation can depend on the follicular status of the ovaries at the time of treatment. Mares with large follicles when given prostaglandin tend to show heat and ovulate sooner than do mares with small follicles. Ovulation occurs in approximately two thirds of mares given prostaglandin that have a large pre-ovulatory size follicle; in approximately one third, the follicle regresses and a second one grows.31 This phenomenon occurs, perhaps, because there is a certain degree of atresia in some of those large follicles at the time of treatment. The use of ovulatory inducing agents such as human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) is common in ET programs. Injection of 1500 IU of hCG intravenously when there is a 35-mm follicle induces ovulation 36–48 hours after injection.32,33 Other ovulatory inducing agents such as deslorelin or Ovuplant are also commonly used in ET programs to tighten the synchrony between donors and recipients. These agents are also used when donor mares have more than one dominant follicle to promote multiple and synchronous ovulations. In our experience, hCG has been useful to synchronize ovulations but not to promote double ovulations.

Meclofenamic acid is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug that has been used successfully to increase the window of synchrony between donors and recipients. It was first used in goats and dromedary camels. Administration of 1 gm daily of meclofenamic acid to recipient mares that had ovulated up to 4 days before the donors showed that acceptable pregnancy rates can be achieved.34

Progesterone Supplementation

The use of ovariectomized mares as embryo recipients was first reported by Hinrichs.35 To use ovariectomized recipients, mares are injected daily with 300 mg of progesterone starting 2 days after donor ovulation. This treatment is continued for 100–110 days if the mare is pregnant. Long-acting progesterone preparations are commercially available that can be administered every 6–7 days.36 Alternatively, the synthetic progestin altrenogest has been used successfully to prepare ovariectomized mares as embryo recipients.37–42 Mares are started on altrenogest orally at a dosage of 0.044 mg/kg of body weight daily from the day of donor ovulation up to day 35 of pregnancy. After this stage, the dose can be lowered to 0.022 mg/kg up to 100–110 days. After 100 days of gestation, both progesterone- and altrenogest-treated mares produce fetal placental progestins that maintain the pregnancy. Endocrine profiles for the remainder of gestation, parturition, and lactation have been reported to be normal.43 The main advantage of using ovariectomized mares is to reduce the number of recipients per donor. In addition there is a significant reduction of labor expenses because there is no need for ovarian control of the recipients. At our clinic, because inexpensive mares are available, we routinely use intact mares.

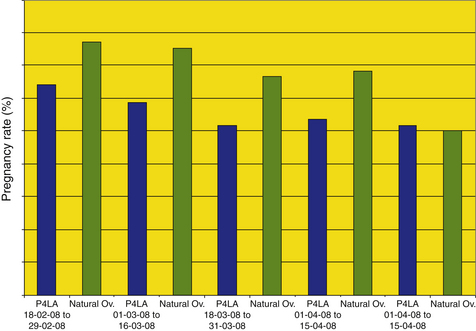

In a study conducted at our clinic (Fig. 16-2), a total of 469 transfers were performed between February 15 and April 30, 2008, comparing pregnancy rates achieved in normal cycling mares vs. intact non-cycling mares supplemented with progesterone.44 The results comparing both groups were analyzed in 15-day periods. Overall, pregnancy rates in anovulatory, progesterone-treated recipients were significantly lower than those for ovulatory recipients (164/192 [56.1%] vs. 197/277 [71.1%]).

Artificial Insemination in Embryo Transfer Programs

In our program, mares are artificially inseminated with fresh, extended semen collected at the center. Only in rare occasions is semen collected at other farms and transported to our center. Mares that are inseminated and ovulate within 24–48 hours after breeding are not rebred if the semen is of good quality and sperm longevity is adequate. Mares that are susceptible to endometritis are inseminated using minimal contamination breeding procedures.45 Ovulations are routinely induced with hCG (1600 IU IV) and artificial insemination performed on the same day or the day after. If ovulation is detected in a mare that has not been inseminated, she is bred immediately as long as she displays good estrous behavior to the teaser and the cervix is still open. Embryo recovery rate in mares inseminated within 12 hours of ovulation resulted in a reduction of recovered embryos (63% vs. 83%). There was no significant difference in the proportion of grade 1 embryos between the groups (76/85 [89%] pre-ovulation vs. 13/19 [68%] post-ovulation). There was no difference in recipient pregnancy rate at days 14–21 (73% pre-ovulation vs 68% post-ovulation).46

Susceptible mares may show signs of endometritis such as heavy uterine edema, fluid accumulation, or vaginal discharge 24 hours after insemination. In such cases, mares undergo a uterine lavage with 2–4 L of sterile saline at body temperature. This procedure can be repeated daily for up to 3 days after ovulation, followed by injection of 20 IU of oxytocin. In some cases, this therapy appears to be beneficial at cleaning the uterine environment to allow for a clear uterine lavage 6–8 days after detection of ovulation. Corticosteroids (0.1 mg/kg of prednisolone acetate) have been used in donor mares with history of intense inflammatory uterine response after AI.47

Uterine Lavage (Flushing) for Embryo Recovery

The equine embryo stimulates oviductal movement and embryo transport through the production of prostaglandin-E2 (PGE2).48,49 The embryo enters the uterus from 5 days 10 hours to 5 days 22 hours after ovulation.48–50 The possible reasons for this variability could be the variable delay between ovulation and fertilization (depending on individual oocytes), embryonic factors related to timing of PGE2 secretion, sex of the embryo, or other individual factors. Because of this variability in the oviductal transport period, uterine lavage or flush for embryo recovery is performed between days 6 and 8 after ovulation. Most authors agree that recovery rate is lower when performed at day 6.24,25 It has been postulated that this can be due to one or more of the following reasons: (1) failure of the embryo to descend into the uterus by day 6, (2) failure of the technician to recover the embryo from the uterus because of a higher gravity weight of the embryo, (3) failure of the technician to find the embryo because of its smaller size, and (4) loss of the embryo at some point during the process.