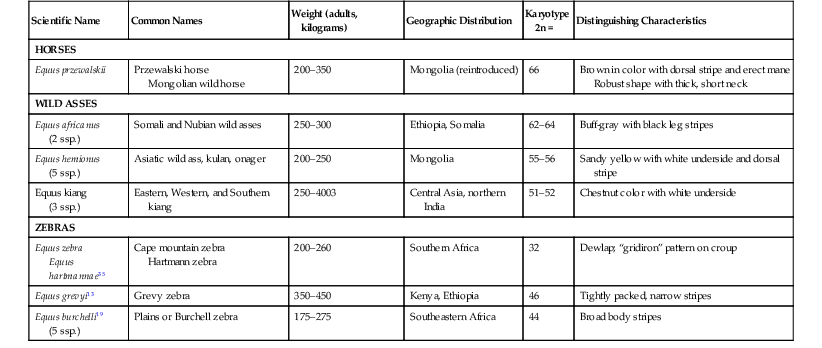

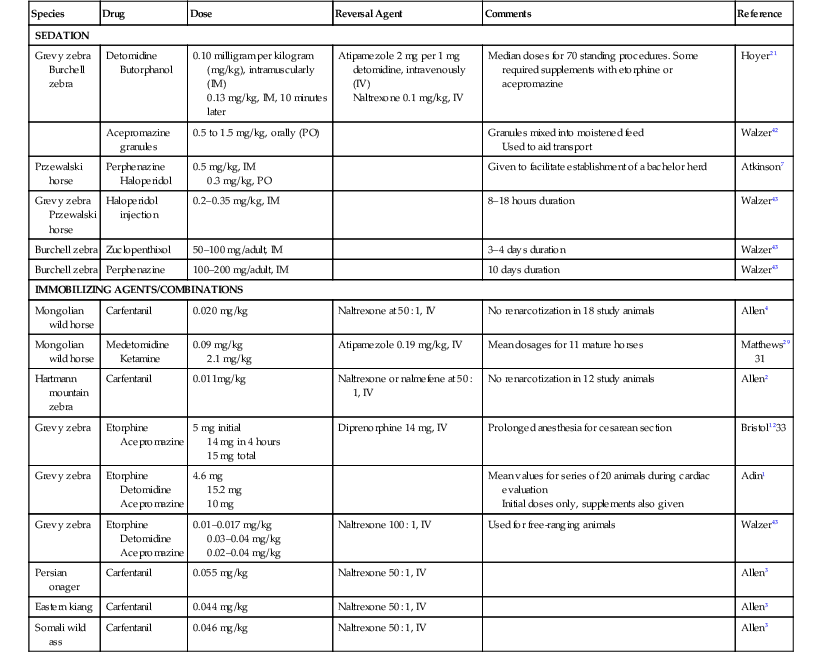

Donald L. Janssen, Jack L. Allen Equidae, Tapiridae, and Rhinocerotidae are families within the mammalian order Perissodactyla and are distinguished from the family Artiodactyla by their foot morphology and digestive system. Equidae is a small family that includes the horses, wild asses, and zebras. The taxonomy of nondomestic Equidae is somewhat dynamic and subject to change. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Equid Specialist Group lists seven species and numerous subspecies of the single genus Equus18 (Table 57-1). Most species are at risk of extinction today. The genus Equus first appeared during the Pliocene Age and was once widespread in grassland and desert habitats through North America, Asia, Africa, and Europe. The current distribution is over open habitats of eastern and southern Africa and regions of Asia. This pattern of significantly reduced distribution from former times is a pattern seen among all perissodactyls. Modern equids tend to live in harsh, dry lands, and many occupy grasslands shared by nomadic peoples. Wild equids generally are polygynous and highly social.18 TABLE 57-1 Biologic Information of Selected Nondomestic Equids, Order Perissodactyla, Family Equidae18 The structure and anatomy of the members of Equidae are quite similar to those of the domestic horse. Nondomestic equids are most easily distinguished by their external appearance. Table 57-1 gives brief descriptions of the distinguishing characteristics of each species. The Przewalski horse is most noted for its horselike appearance. The Asian and African wild asses are distinguished by the solid and subtle color patterns on their bodies and legs. The various zebra species have distinct striping patterns and characteristics that differentiate them by species and even as individuals. The internal anatomy of equids is analogous to that of the domestic horse and other Perisodactyla species. Equids are bulk-feeding herbivores with large body mass. The dental formula is: incisors (I) 3/3, canines (C) 1/1, premolars (P) 3-4/3, molars (M) 3/3) for a total of 40 to 42 teeth. The canine teeth are vestigial or absent in females. Their cheek teeth have high crowns and relatively short roots (hypsodont). Their gastrointestinal (GI) anatomy has a structure and function designed for hindgut fiber fermentation, with a relatively small stomach and large cecum and colon. The foot posture is unguligrade, bearing weight on one functional digit. Minor differences exist in external foot anatomy in nondomestic equids compared with domestic horses. In general, nondomestic horses have smaller feet compared with domestic horses. Specifically, the Przewalski horse’s hoof is the most similar to the domestic horse but a little smaller. The foot has a strong and robust appearance, with the ratio of frog to sole being identical to that of domestic horses. The Grevy zebra’s foot is similar to that of a mule or donkey and is narrower and more upright than that of domestic horses. The frog-to-sole ratio is less than that in the domestic horse. The mountain zebras have a smaller foot than the Grevy zebra but otherwise similar. The African wild asses’ feet are similar to those of zebras but are less robust in appearance. The Asian wild asses’ feet are similar to those of the African asses except that they have a more robust structure. Most equids are managed in a similar way in zoos. Equids are generally hardy and withstand normal to severe temperature variations as long as shelter and protection from wind and sun are available. Equids acclimated to the southern California climate do well in temperatures ranging from 0° C to over 38° C. Grevy zebras are reported to be less cold tolerant in zoos compared with other zebras.13 Shelter should be provided to keep food dry and to provide shade. Although wild equids may go without water for long periods in the wild, they drink water when it is accessible, so they should have a constant supply of fresh water when managed in zoos. Periodic hoof trimming is needed in some individuals and under certain management conditions. Some species of equids (e.g., mountain zebras and Przewalski horses) seem to require more frequent hoof trimming compared with others. Przewalski horses, for example, may require trimming every 6 to 9 months.37 Some interactions and introductions among equids may be quite violent and aggressive, resulting in injuries from kicking or from bite wounds on the neck or tail area. Several cases of infanticide have been documented in wild equids.16 Care should be exercised when introducing a male to a new herd or a pregnant female to a new stallion. Stallions may be aggressive toward new foals, so mares that are close to foaling should be separated from stallions. Stallions may also be aggressive toward keepers, and extreme caution should be used when working around them.37 All equids are bulk-feeding grazers, feeding primarily on grass and roughage. In the wild, grass constitutes over 90% of the common zebra’s diet. They may resort to some browsing and digging of plant materials in the dry periods. Grevy zebras reportedly eat some browse in the wild.19 As with other perissodactylids, equids are hind gut fermenters and have a large cecum and colon. In general, nondomestic equids have no specialized feeding requirements and may be fed like domestic equines. Specifically, feeding a diet combining high-fiber pellets and grass hay to nonruminant grazers in zoos is recommended. The pellet serves as a source of nutrients and may be designed to compensate for specific regional dietary deficiencies or for deficiencies in the hay. In regions where enteroliths are a problem, reducing or eliminating alfalfa in the pellet or hay source is advisable. Pellet and hay may be fed at a ratio of approximately 50% pellet to 50% hay. Intake should be about 1.5% to 3.0% body weight.25 In group-housed animals, adequate feeders are necessary to avoid competition from dominant animals. Salt and trace mineral blocks may be used if the pelleted diet cannot be specially formulated. Feeding of produce is not recommended, since readily fermentable substances may lead to digestive upset. Often, these items are desired for behavioral husbandry or enrichment. It is recommended that produce be offered at no more than 2% to 5% of the diet on a dry-matter (DM) basis.25 The document “Nutrient Requirement for Horses,” from the National Research Council (NRC) may be consulted for specific nutrient and energy requirements for maintenance, growth, gestation, and lactation.14 Obesity may be a problem in nondomestic equids maintained in zoo environments. Encouraging exercise and restricting the amount of pelleted feed may help. A body scoring system may be used to track body condition and used as an objective assessment of obesity.11,14 Physical restraint is not often practical in adult equids because of their size and strength. Newer hydraulic hugger restraint chutes do make it possible to restrain nondomestic equids, usually with the aid of chemical restraint (Table 57-2). Blood sampling and other minor procedures are then possible.21 Animal care staff must work cautiously around any nondomestic equid because they may startle and bolt unexpectedly into solid obstacles, which may result in fatal neck or head injuries. TABLE 57-2 Chemical Restraint Agents Used in Equids Several authors provide regimens for successful chemical restraint of equids under both captive and free-ranging conditions (see Table 57-2). Acepromazine granules and oral haloperidol are effective for oral sedation to aid in acclimation to new housing or for transport. Injectable short-acting sedatives such as xylazine, acepromazine, and butorphanol may be used. Long-acting neuroleptic sedatives may be used as injectable drugs, sometimes in combination and staged to achieve the desired length of sedation. Haloperidol is a short-acting agent and has a relatively rapid onset of 5 to 10 minutes and a duration of 8 to 18 hours. Zuclopenthixol is a medium-acting drug and has an onset of action in 1 hour and a duration of action of about 3 to 4 days. Finally, perphenazine is a long-acting drug that has an onset of action in 12 to 16 hours and duration of 10 days.43 These drugs may occasionally cause extrapyramidal signs such as hyperexcitability and incoordination. A detailed review of long-acting neuroleptic tranquilizers in equids is provided elsewhere.43 For full immobilization, opioid narcotics are the primary agents available. Etorphine is the most commonly used agent because of its familiarity, availability, and reliability in most species of equids. It is most often used in combination with α2-agonists, ketamine, phenothiazine tranquilizers, or a combination of these agents. Carfentanil has also been used with the Przewalski horse and Hartmann mountain zebras (see Table 57-2). In the authors’ experience, carfentanil has been less consistent and more unpredictable in onagers, kiangs, and Somali wild asses. Carfentanil is largely ineffective and thus not a good choice for anesthetizing Grevy zebras. Another narcotic opioid, thiafentanil (A3080), shows promise for anesthetizing nondomestic equids. Opioids generally cause significant muscle rigidity. When opioids are used alone, the animals often will not become recumbent on their own and may require “casting” to achieve recumbency. This may be avoided by using α2-agonists prior to or along with administration of the opioid. Supplemental drugs such as guaifenesin (5% solution given intravenously [IV] to effect) or propofol (1% solution 3 to 5 mg/kg, IV, to effect) may be used to provide sufficient relaxation during field procedures. Relaxation is important to allow adequate ventilation depth, tidal volume, and intubation, if desired. Renarcotization following etorphine anesthesia and diprenorphine reversal has been shown to range from approximately 5% to 10%.5 A review of alternative non-narcotic anesthetic agents for chemical immobilization of equids covered several drug categories, including α2-agonists, benzodiazepines, butyrophenones, and others, which might be useful if potent opioid narcotics are not available.30 Besides the chemical agents themselves, several other factors need to be considered when immobilizing nondomestic equids. A well-thought-out plan is critical for success. Some factors to consider include (1) obtaining an accurate body weight, (2) work with experienced or trained support staff, (3) precise dart placement, (4) advantages and disadvantages of preanesthetic medications, (5) the prevalence of renarcotization in the species, and (6) a safe, appropriate area for recovery. Although regurgitation is not a risk, food and water must be withheld for 18 to 24 hours prior to a planned procedure to reduce GI volume. During hot weather, it is probably best to provide water during the fasting period. Anesthetic drugs may be administered with a variety of remote delivery devices. If the horse is nervous and excited prior to darting, achieving the desired effect of the anesthetic drugs may be made more difficult. Dart location is ideally in a large muscle mass such as the gluteals, shoulder, or neck region, but areas of fat should be avoided. Horses generally do well in lateral recumbency when under anesthesia and do not need to have the head elevated. Blindfolds and ear plugs are useful to decrease stimulation. It is recommended that supplemental oxygen be provided via a mask or a nasal cannula, at a flow rate of 6 to 10 liters per minute (L/min). At a minimum, anesthesia monitoring should include heart rate and rhythm, rate and depth of ventilations, and oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry. Using a veterinary clip sensor, pulse oximetry is usually successful on the tongue, ear pinna (clipped and scraped of superficial pigment), vulva, prepuce, or eyelid (reflectance sensor). Once equids are immobilized with chemical restraint, many minor procedures such as physical examination, diagnostic sampling, hoof care, and assisted birthing may be performed. For prolonged procedures such as dental work, radiography, extensive diagnostics, and abdominal surgery, general anesthesia and additional monitoring are recommended. Isoflurane works well for maintenance of inhalation anesthesia in equids. Mechanical ventilation is recommended. Intermittent intravenous propofol may be used to extend the anesthesia. Performing endotracheal intubation is straightforward in nondomestic equids. Blind intubation, as in the domestic horse, is the usual method. Direct visualization of the larynx is not difficult with proper positioning and the use of a long laryngoscope blade. With either technique, it is important to have the animal adequately relaxed and its neck fully extended in the dorsal direction. Indirect blood pressure may be measured with an appropriate-sized cuff placed around the metacarpal or metatarsal area. Arterial samples for blood gas determination may be obtained from the facial artery or the intermediate branch of the caudal auricular artery. End-tidal carbon dioxide (CO2), a direct arterial line in the facial artery for direct blood pressure, and electrocardiography (ECG) are also useful in monitoring horses under prolonged anesthesia. ECG parameters in Grevy zebras have been described elsewhere.32 As in the domestic horse, acute abdominal discomfort is not uncommon in nondomestic equids. Some cases require surgery. Enterolith-associated colic requiring rapid surgical intervention has been reported.20 See Table 57-7.

Equidae

General Biology

Scientific Name

Common Names

Weight (adults, kilograms)

Geographic Distribution

Karyotype

2n =

Distinguishing Characteristics

HORSES

Equus przewalskii

Przewalski horse

Mongolian wild horse

200–350

Mongolia (reintroduced)

66

Brown in color with dorsal stripe and erect mane

Robust shape with thick, short neck

WILD ASSES

Equus africanus

(2 ssp.)

Somali and Nubian wild asses

250–300

Ethiopia, Somalia

62–64

Buff-gray with black leg stripes

Equus hemionus

(5 ssp.)

Asiatic wild ass, kulan, onager

200–250

Mongolia

55–56

Sandy yellow with white underside and dorsal stripe

Equus kiang

(3 ssp.)

Eastern, Western, and Southern kiang

250–4003

Central Asia, northern India

51–52

Chestnut color with white underside

ZEBRAS

Equus zebra

Equus hartmannae35

Cape mountain zebra

Hartmann zebra

200–260

Southern Africa

32

Dewlap; “gridiron” pattern on croup

Equus grevyi13

Grevy zebra

350–450

Kenya, Ethiopia

46

Tightly packed, narrow stripes

Equus burchelli19

(5 ssp.)

Plains or Burchell zebra

175–275

Southeastern Africa

44

Broad body stripes

Unique Anatomy

Special Housing Requirements

Feeding

Restraint and Handling

Species

Drug

Dose

Reversal Agent

Comments

Reference

SEDATION

Grevy zebra

Burchell zebra

Detomidine

Butorphanol

0.10 milligram per kilogram (mg/kg), intramuscularly (IM)

0.13 mg/kg, IM, 10 minutes later

Atipamezole 2 mg per 1 mg detomidine, intravenously (IV)

Naltrexone 0.1 mg/kg, IV

Median doses for 70 standing procedures. Some required supplements with etorphine or acepromazine

Hoyer21

Acepromazine granules

0.5 to 1.5 mg/kg, orally (PO)

Granules mixed into moistened feed

Used to aid transport

Walzer42

Przewalski horse

Perphenazine

Haloperidol

0.5 mg/kg, IM

0.3 mg/kg, PO

Given to facilitate establishment of a bachelor herd

Atkinson7

Grevy zebra

Przewalski horse

Haloperidol injection

0.2–0.35 mg/kg, IM

8–18 hours duration

Walzer43

Burchell zebra

Zuclopenthixol

50–100 mg/adult, IM

3–4 days duration

Walzer43

Burchell zebra

Perphenazine

100–200 mg/adult, IM

10 days duration

Walzer43

IMMOBILIZING AGENTS/COMBINATIONS

Mongolian wild horse

Carfentanil

0.020 mg/kg

Naltrexone at 50 : 1, IV

No renarcotization in 18 study animals

Allen4

Mongolian wild horse

Medetomidine

Ketamine

0.09 mg/kg

2.1 mg/kg

Atipamezole 0.19 mg/kg, IV

Mean dosages for 11 mature horses

Matthews29 31

Hartmann mountain zebra

Carfentanil

0.011mg/kg

Naltrexone or nalmefene at 50 : 1, IV

No renarcotization in 12 study animals

Allen2

Grevy zebra

Etorphine

Acepromazine

5 mg initial

14 mg in 4 hours

15 mg total

Diprenorphine 14 mg, IV

Prolonged anesthesia for cesarean section

Bristol1233

Grevy zebra

Etorphine

Detomidine

Acepromazine

4.6 mg

15.2 mg

10 mg

Mean values for series of 20 animals during cardiac evaluation

Initial doses only, supplements also given

Adin1

Grevy zebra

Etorphine

Detomidine

Acepromazine

0.01–0.017 mg/kg

0.03–0.04 mg/kg

0.02–0.04 mg/kg

Naltrexone 100 : 1, IV

Used for free-ranging animals

Walzer43

Persian onager

Carfentanil

0.055 mg/kg

Naltrexone 50 : 1, IV

Allen3

Eastern kiang

Carfentanil

0.044 mg/kg

Naltrexone 50 : 1, IV

Allen3

Somali wild ass

Carfentanil

0.046 mg/kg

Naltrexone 50 : 1, IV

Allen3

Chemical Restraint

Surgery

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree