Chapter 13 Enteral Nutrition

DETERMINING THE ROUTE OF NUTRITIONAL SUPPORT

Enteral Versus Parenteral

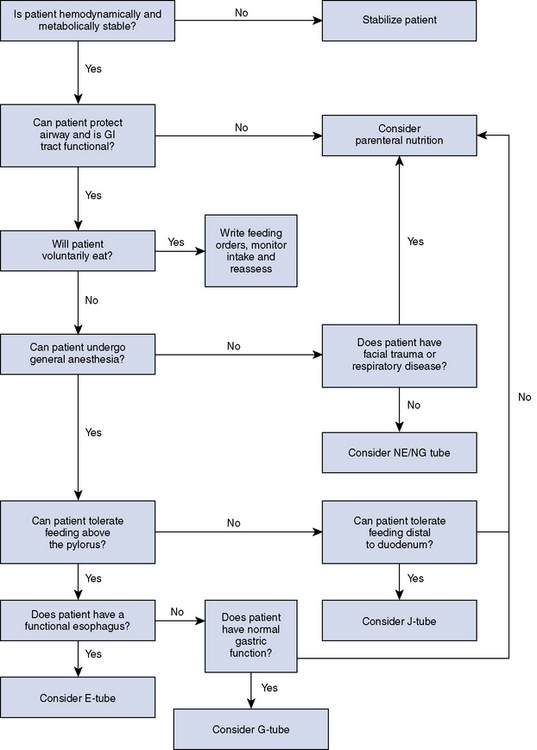

Nutritional support can be delivered via the GI tract (enteral route), via the vasculature (parenteral route), or using a combination of the two. Both routes require a hemodynamically stable patient with no major acid-base or electrolyte abnormalities. The route of nutrient delivery is determined by patient factors such as GI function and ability to protect the airway, and nonpatient factors such as cost, predicted length of hospitalization, technical expertise, and level of patient monitoring. Enteral feeding is preferable to parenteral feeding because it is physiologically sound, less costly, and safer.5 The physiologic benefits of enteral feeding include prevention of intestinal villous atrophy, maintenance of intestinal mucosal integrity, which decreases the risk of bacterial translocation, and preservation of GI immunologic function. Contraindications for enteral feeding are uncontrolled vomiting, GI obstruction, ileus, malabsorption or maldigestion, or inability to protect the airway. However, if the patient is unable to protect the airway, the clinician may select a route of nutrient delivery distal to the pharynx or esophagus if the concern is aspiration during swallowing, or distal to the pylorus if the concern is aspiration during vomiting or regurgitation. Figure 13-1 outlines the decision process for selecting an appropriate enteral feeding route.

Oral Intake Versus Enteral Feeding Device

An enteral feeding tube removes the variable of voluntary intake. The technical staff delivers a prescribed amount of a specific diet via the feeding tube according to orders written by the veterinarian. These tubes are well tolerated by veterinary patients. A retrospective owner survey concluded that owners were comfortable managing their cats at home with esophagostomy and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tubes.6 However, enteral feeding device placement usually requires sedation or anesthesia and technical skill. Technicians and owners must be taught how to use feeding devices and monitor for complications. Table 13-1 outlines advantages and disadvantages of the various forms of enteral access used in veterinary patients.

Table 13-1 Advantages and Disadvantages of Enteral Feeding Devices

| Enteral Feeding Device | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| NE or NG tube | Ease of placement No general anesthesia NG tube allows for gastric decompression | Limited to liquid diets Short term (<14 days) Can be irritating; requires E-collar Can dislodge if patient sneezes or vomits Contradicted in facial trauma or respiratory disease Increased risk of vomiting with NG vs NE tube |

| Esophagostomy tube | Blenderized pet foods or liquid diets can be used Well tolerated by patient Ease of placement Can feed as soon as patient awakens from anesthesia Can be removed at any time Good long-term option | Requires general anesthesia Risk of cellulitis or infection at site Can dislodge if patient vomits Can cause esophageal irritation or reflux if malpositioned |

| Gastrostomy tubes | Blenderized pet foods or liquid diets can be used Well tolerated by patient Good long-term option | Requires general anesthesia Risk of cellulitis or infection at site Risk of peritonitis Must wait 24 hours after placement before feeding Must wait 10 to 14 days before removing |

| Jejunostomy tube | Requires liquid diet Able to feed distal to pylorus and pancreatic duct | Requires general anesthesia Technically more difficult to place Risk of cellulitis or infection at site Risk of peritonitis Risk of tube migration with secondary GI obstruction Must wait 24 hours after placement before feeding Requires CRI feeding Requires very close monitoring Short-term option |

CRI, Constant rate infusion; GI, gastrointestinal; NE, nasoesophageal; NG, nasogastric.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree