Chapter 8 Endoscopic Biopsy Specimen Collection and Histopathologic Considerations

This chapter will provide commentary on the following topics:

Practical Considerations for Endoscopic Biopsy

Endoscopic examination and biopsy of the GI tract can be diagnostic of many mucosal disorders. However, endoscopy is an adjunctive procedure that complements information gained from a history, physical examination, selected laboratory and imaging studies, and well-designed therapeutic trials. Endoscopic biopsy is useful in detecting morphologic disease but typically fails to detect functional disorders, including abnormal GI motility, GI secretory disorders, and biochemical injury such as brush border enzyme deficiencies. A variety of clinical disorders characterized by primary or secondary GI signs but no significant changes in tissue morphologic features are commonly encountered (Box 8-1).

BOX 8-1 Gastrointestinal Diseases That Can Often Be Unaccompanied by Significant Histopathologic Lesions

Examination and Description of the Mucosa

A thorough, systematic examination of mucosal structures should precede all biopsy procedures because postbiopsy hemorrhage may obscure lesions. Excellent descriptive summaries of normal endoscopic mucosal examinations are provided elsewhere in this book. Recently, an attempt to standardize the procedure for upper and lower GI endoscopic examinations, as well as the descriptive terminology used to record the findings of the process, was produced by the WSAVA Gastrointestinal Standardization Group. The goal of this group was to ensure that a standardized protocol for performing thorough and complete endoscopic examinations was available for clinicians to use in practice. These protocols should also prove valuable for investigators undertaking multicenter clinical trials in which consistent endoscopic examination and biopsy specimen procurement are essential. Clinicians using these forms simply check off endoscopic observations, and these forms can then become a quick and convenient part of the patient’s medical record. The forms are available online and have been endorsed by the Comparative Gastroenterology Society and the European Society of Comparative Gastroenterology (http://www.wsava.org/StandardizationGroup.htm). These forms were not intended to be the final answer; rather, they incorporate features that are deemed valuable such as tick boxes, the ability to comment on the presence/absence of all possible lesions, and an area for identification of the extent of the examination, the equipment used, and any complications associated with the procedure. Videotape or photographic records serve to complement the endoscopic report on each animal. The important features of each endoscopic procedure should be documented (Box 8-2).

Consistent endoscopic terminology has been proposed to aid in lesion description and the formulation of a definitive diagnosis (Box 8-3). Erythema denotes mucosal redness, which may be a pathologic condition or a normal physiologic response to excessive insufflation or blood flow changes associated with anesthesia. Friability describes the ease with which the mucosa is damaged by contact with the endoscope or biopsy instrument. Alterations in surface texture are described as increased granularity. Granularity of the small intestinal mucosa may be influenced by villus height and crypt depth as the light of the endoscope reflects off these structures. Mass lesions are commonly seen with infiltrative mucosal diseases (e.g., inflammatory disorders, malignant neoplasia, and benign polyps) and may be pedunculated or sessile. As previously noted, masses should be sampled deeply to avoid misdiagnosis.

GI ulceration or erosion is defined as an endoscopically visible breach in mucosal integrity, which may or may not be associated with active hemorrhage. Ulcers are typically solitary, crateriform, well-circumscribed lesions that extend deeply into the mucosa and contain central fibrinous exudate. Erosions are discrete, superficial mucosal defects without raised margins or necrotic centers. Ulcers and erosions are characteristic of inflammatory and neoplastic lesions. Erosive lesions should be sampled directly. Ulcerative lesions should usually be sampled by obtaining specimens from the ulcer rim, where it merges with adjacent tissue. Alternatively, where ulcers are associated with lesions such as scirrhous gastric carcinoma in dogs, a diagnosis may sometimes only be achieved by sampling tissue as deeply as possible within the ulcer itself. Mucosal specimens from tissues surrounding an ulcer should also be procured to characterize benign from malignant ulcerative disease. Mucosal biopsy specimens obtained from focal lesions (e.g., ulcer, masses) should be placed in a separate biopsy cassette to distinguish the histopathologic features of these lesions from the histopathologic changes in biopsy specimens obtained from normal-appearing or less involved areas of mucosa.

Instrumentation for Specimen Collection

Pinch Biopsy Forceps

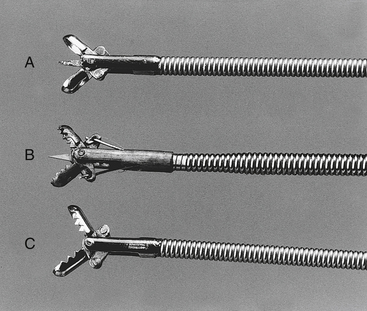

Flexible, pinch biopsy forceps are most commonly used to obtain mucosal specimens from the GI tract. These small, flexible forceps with opposing 2- to 3-mm cups on their distal end are passed through the operating channel of the endoscope. There are numerous configurations (i.e., cups may be smooth or serrated, standard or fenestrated, with or without a central needle; forceps may be multiple use or disposable, and some are designed to allow multiple samples to be taken before withdrawing the instrument) (Figure 8-1). Fenestrated forceps are reported to cause fewer crush artifacts and yield larger biopsy specimens than nonfenestrated models. There is a lack of uniformity of opinion between endoscopists as to the best configuration for endoscopic biopsy forceps. Biopsy forceps with central needles can help stabilize the forceps and are useful for some endoscopists but in the hands of other clinicians yield inferior tissue samples. Endoscopists will need to decide which type works best in their own hands.

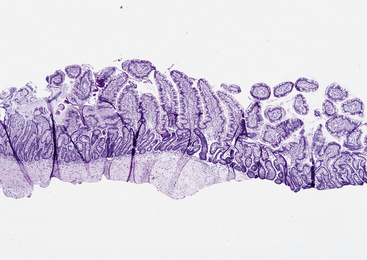

Recent work has shown that the diagnostic quality of the endoscopic sample influences the likelihood that a pathologist will find a specific mucosal lesion. In general, six marginal or adequate samples should be collected to detect abnormalities in the feline gastric and duodenal mucosa, whereas six adequate or 10 to 15 marginal samples should be collected from the canine stomach and duodenum, depending on the lesion being sought. To be considered adequate, a biopsy sample should contain the full thickness of the mucosa and be wide enough to have at least three to four intact and preferably contiguous villi. Specimens containing submucosa are preferred, but it is not always possible to obtain tissue at this level, especially when the mucosa is relatively thick (e.g., large versus small dog; duodenum versus ileum) (Figure 8-2).

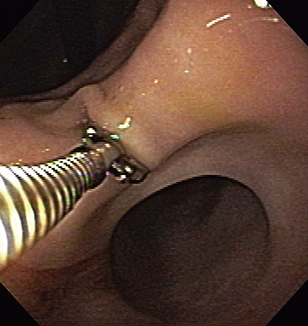

There are various techniques for sampling GI mucosa with flexible endoscopic forceps. We each have our preferences, but any technique that consistently works for an individual is acceptable. The procedure may be performed solely by the endoscopist; however, having an assistant to operate the biopsy forceps is advantageous. It is generally desirable to position the endoscope tip directly in front of and perpendicular to the area to be sampled (Figure 8-3). This may be difficult or impossible in smaller patients (e.g., cats) in which the intestinal lumen is relatively narrow. The pinch biopsy instrument is passed through the operating channel and extended beyond the tip of the endoscope, the jaws are opened, and the instrument is advanced into the mucosa with the use of forward pressure. In the case of animals with a small diameter intestinal lumen (e.g., small dogs and cats), one may first advance the forceps, open them, retract the tip of the forceps against the tip of the endoscope, and then maximally deflect the tip of the endoscope obliquely into the mucosa in an attempt to achieve as perpendicular an orientation as possible. This typically makes it impossible to visualize the mucosa (i.e., a “red out”), but it may allow one to advance the insertion tube tip into the mucosa at a more nearly vertical angle. Larger, deeper, and more diagnostically significant specimens are usually obtained by application of pressure at the time of biopsy, but if so much pressure is applied that the tip of the forceps turns and does not approach the tissue directly, then inferior samples may be obtained. Larger forceps (e.g., those that can pass through an accessory channel diameter of at least 2.8 mm) usually yield better quality specimens, although areas with relatively thin mucosa (e.g., ileum and feline duodenum) may be adequately sampled with smaller forceps (e.g., those that can pass through an accessory channel diameter of 2.2 mm or less). Adequate forward pressure is evidenced by displacement of the tissue away from the endoscope and gentle “bowing” of the biopsy instrument shaft (but not the tip of the forceps). The jaws of the forceps are then closed firmly, the instrument is retracted to the endoscope tip, and a firm steady tug is used to tear a tissue sample free. Except for the gastric antrum near the pylorus, it is not necessary to forcefully jerk the forceps back into the endoscope. If a forceful jerk is deemed necessary, it is important to straighten the tip of the endoscope to help avoid damage to the biopsy channel. The forceps instrument is withdrawn from the operating channel, and the tissue specimen is carefully removed from the open jaws of the forceps for processing. Specimens may also be used to make touch imprints for cytologic evaluation.

Cytology Brushes and Catheters

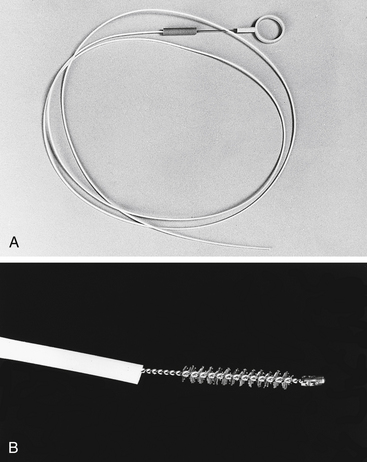

Disposable guarded cytology brushes are useful for obtaining cell specimens. These brushes are passed through the operating channel of the endoscope under direct guidance and are protected from contamination by an outer sheath (Figure 8-4). Once the area to be sampled is identified, the brush is extended from its sheath, rubbed vigorously against the mucosa or surface of the lesion without causing excessive hemorrhage, and then retracted into the operating channel. The brush cytology instrument is then removed from the endoscope. Superficial cells and cellular debris are then rolled or rubbed onto microscopic slides, air dried, stained with a Romanowsky-type stain (e.g., Diff-Quik), and examined microscopically for evidence of inflammation, neoplasia, or infectious agents. Alternatively, touch cytology may be performed by transferring a mucosal specimen from the biopsy forceps to a glass slide with a needle and then gently touching the specimen onto the slide so that a cytologic imprint is obtained.

Figure 8-4 A, Disposable guarded cytology brush. B, Close-up of brush extended beyond its protective sheath.

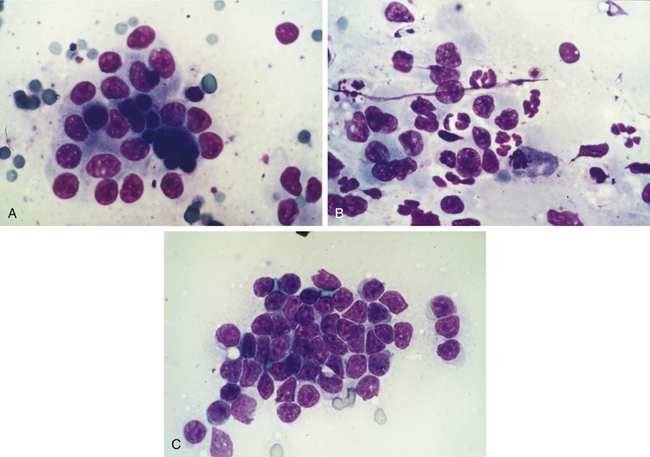

In a more comprehensive investigation, brush and touch cytologic specimens were obtained by endoscopic examination of the stomach (n = 49), small intestine (n = 47), and colon (n = 18) in 44 dogs and 14 cats. All cytologic smears were blindly reviewed and objectively graded for inflammatory cellularity, cellular atypia, bacterial organisms, hemorrhage, and background mucus and debris. In each case a cytologic diagnosis was rendered and compared with the histologic findings. Excellent correlation between cytologic observations and histopathologic features was observed. For detecting abnormalities, the examination of endoscopically obtained cytologic specimens was found to have a sensitivity and specificity of 100% and 92% for the stomach, respectively, 93% and 93% for the small intestine, respectively, and 88% and 88% for the colon, respectively. A similar diagnosis was made for both cytologic and histologic specimens determined to be normal or to have lymphoplasmacytic inflammation, mixed inflammation, eosinophilic inflammation, and lymphoid malignancy (Figure 8-5). Brush cytology was most useful in detecting lamina propria cellular infiltrates; touch cytology was more likely to detect acute mucosal inflammation as evidenced by increased numbers of neutrophils. These results indicate that exfoliative cytology is a useful and reliable adjunct to endoscopic biopsy. Nevertheless, endoscopic cytology is probably underutilized as a clinical diagnostic tool for primary GI disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree