CHAPTER 6 Endodontic Disease

Radiography is a vital component of veterinary endodontic treatment. Radiographs provide information about the presence, nature, and severity of periapical and root pathology. This information is essential for the diagnosis of endodontic disease as well as for the prognosis of its treatment. Radiographs do not provide direct information about pulp health; however, many of the effects of pulp pathology are radiographically visible.

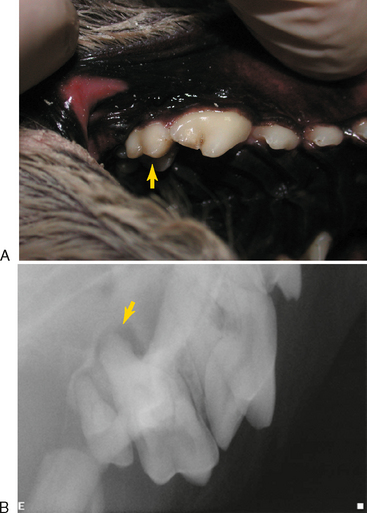

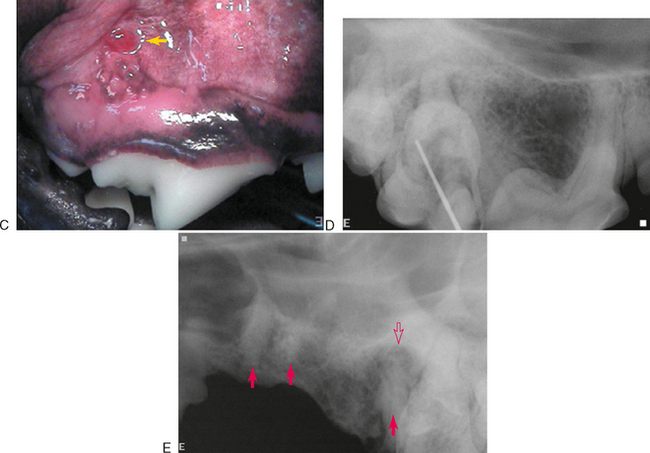

Clinical findings that may indicate the presence of endodontic disease include a fractured tooth with exposure of the pulp chamber, a discolored tooth, or an intraoral or extraoral draining fistula. Except in the obvious case of a direct pulp exposure, a definitive diagnosis of endodontic pathology is difficult to make based only on clinical examination of veterinary patients due to the limitations of pulp testing and lack of patient input. Also, endodontic disease can be present with very little clinical evidence. This is particularly true of maxillary molar teeth that can develop severe periodontitis with extension to the endodontic tissues while exhibiting no clinical signs other than slight mobility (Figure 6-1).

Human patients with endodontic pathology experience various symptoms that range from very mild discomfort when the tooth is loaded in the presence of apical periodontitis, to severe persistent pain when there is an acute apical abscess. These symptoms alert human patients to the existence of a problem, which they can communicate to a dentist. In contrast, veterinary patients often tolerate significant discomfort without complaint. We are forced to rely on radiographic evidence of endodontic disease (Figure 6-2). Radiographs should be made of teeth that are fractured, close to a draining fistula, intrinsically discolored, anomalous, or compromised from periodontal disease to determine the extent of the problem and to evaluate the endodontic and periradicular health.

Dental radiographs can be misleading and unreliable. Early endodontic disease may not show any radiographic abnormalities, while superimposed anatomy can mimic endodontic disease on a radiograph of a healthy tooth. Despite these limitations, dental radiographs continue to be the best tool available to evaluate endodontic health in veterinary patients. It is important for veterinarians to become familiar with radiographic assessment of periapical tissues. In humans, it has been determined that both the accuracy of diagnostic decisions and the probability of appropriate treatment decisions increased when a dentist was confident about his or her diagnosis or treatment. It seems likely that this also holds true for veterinarians practicing dentistry. The more confidence we have in our radiographic diagnosis of pathology, the better and more efficient will be the treatment we provide for our patients.

Radiographic Signs of Endodontic Disease

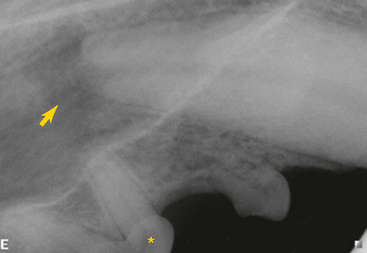

Inflammation caused by endodontic disease affects the surrounding bone and teeth, resulting in changes that can be radiographically detected. Radiographs that are meant to evaluate the periapical tissues should include the entire root tip and surrounding bone (Figure 6-3). They should also be well positioned to avoid elongation, foreshortening, angulation, or distortion of the image. The compact bone that forms the walls of the alveolus (the white line of the lamina dura on radiographs) is also referred to as a cribriform plate due to its multiple perforations for vessels and nerves. This bone is very sensitive to inflammatory mediators that originate in the pulp and escape into the surrounding periodontal ligament. The bone responds with osteoclastic resorption. The characteristic radiographic lesion of endodontic origin (LEO) involves changes in the periapical radiodensity or detail that result from apical periodontitis. LEOs can also develop along the lateral aspect of a root at the site of a lateral canal. Other radiographic signs of endodontic disease are caused by the effects of inflammation or pulp death on the tooth itself.

Radiographic signs of endodontic disease that are associated with the tooth itself include:

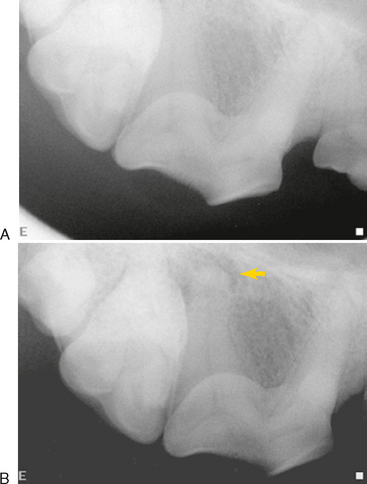

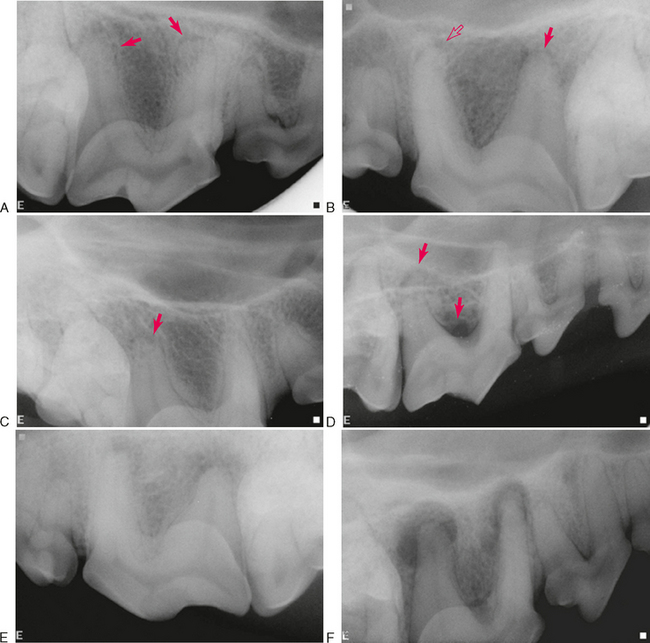

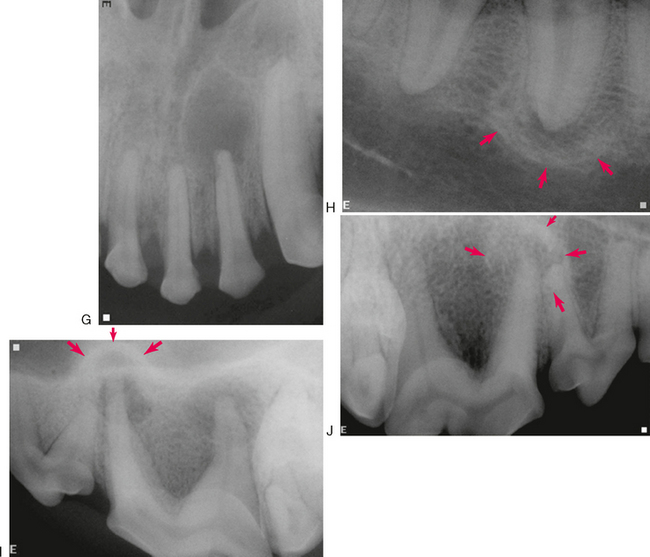

A necrotic or severely inflamed pulp produces inflammatory mediators that can exit the tooth through the apical delta and lateral canals, stimulating leukocyte infiltration and edema. Inflammatory bone resorption at these sites form radiographic LEOs. The earliest extracanal inflammation to occur is usually acute apical periodontitis. Radiographically, this either appears as widening of the apical periodontal ligament space or as no change at all (Figure 6-4, A). Bone and root resorption occur at this stage but the changes may be too small to appear radiographically; lack of a radiographic lesion does not rule out early endodontic disease. Another early radiographic sign is loss of the apical lamina dura (Figure 6-4, B–D). This is also not a reliable indicator of disease because the apical lamina dura frequently becomes unidentifiable when there is insufficient overlying radiodense tissue. Humans report sensitivity to percussion at this early stage when radiographic changes are difficult to identify.

Another acute form of disease is an acute apical abscess caused by severe inflammation from a necrotic pulp. Radiographically, this can range from increased width of the periodontal ligament space to a large region of mild-to-moderate periapical lucency with indistinct borders (Figure 6-4, E). When an abscess subsides, much of the demineralized bone can remineralize, resulting in a smaller radiolucency that has more definite borders.

Chronic apical periodontitis usually results in formation of a cyst or granuloma that appears radiographically as an obvious radiolucency with distinct borders (Figure 6-4, F, G). This can be associated with minimal symptoms in humans. The border of the cyst or granuloma can also show evidence of increased radiopacity due to sclerosing osteitis or focal sclerosing osteomyelitis (Figure 6-4, H). When this expands the alveolar bone into the nasal cavity, it can appear radiographically similar to the “antral halo” described in humans. The palatal root of the maxillary fourth premolar tooth in dogs can create a similar halo effect where the expanding bone protrudes upward into the nasal cavity (Figure 6-4, I). Another form of chronic apical periodontitis is condensing, or sclerosing, osteitis that appears as a diffuse increase in radiodensity with or without a radiolucency (Figure 6-4, J).

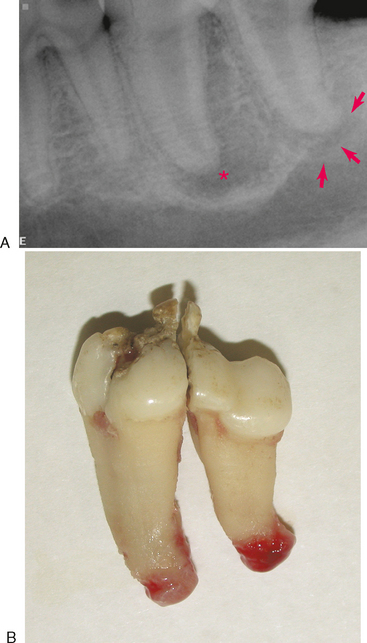

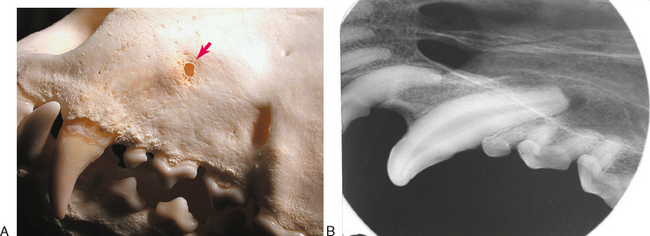

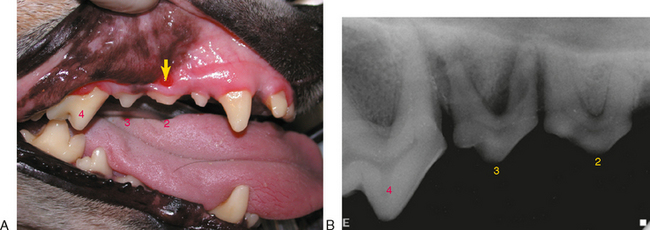

Although the features of a radiographic lucency can suggest the nature of the apical lesion, they cannot reliably distinguish between an apical cyst, granuloma, or abscess. Extracted teeth that are endodontically affected frequently have granulomatous tissue attached to the root tips (Figure 6-5). Apical inflammation can progress to suppurative apical periodontitis. When this occurs, the inflammation and suppuration can dissect through tissues (Figure 6-6) to form a draining fistula. Fistulas from endodontically involved maxillary incisor and canine teeth commonly exit at the mucogingival line (MGL) directly below the root apex, while fistulas from affected premolar teeth commonly appear at the MGL in the furcation area. This is because the inflammatory process dissects through tissues following the path of least resistance. After traveling under the loosely attached alveolar mucosa, it encounters the firmly attached gingiva where it deviates to the surface at the mucogingival line. The mesiobuccal and distal roots of the maxillary fourth premolar tooth often drain externally on the skin of the face below the eye, where it can be misdiagnosed as a primary skin problem unrelated to the teeth. Mandibular canine teeth commonly drain in the vestibular mucosa or skin of the ventral mandible, and mandibular first molar teeth commonly drain intraorally in the interradicular area but can also dissect to more remote locations. The site of exit does not always directly correlate to the problem tooth. Radiographs are needed to determine which tooth is involved (Figure 6-7).