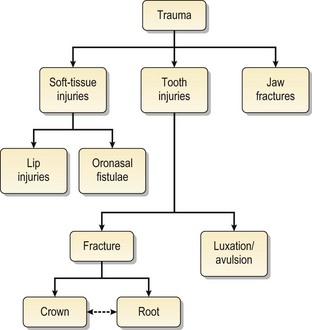

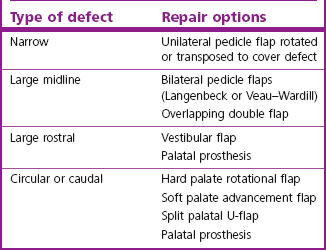

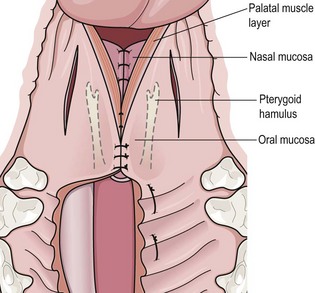

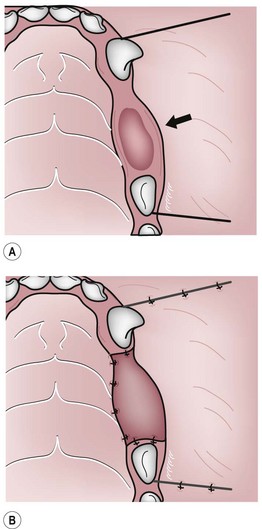

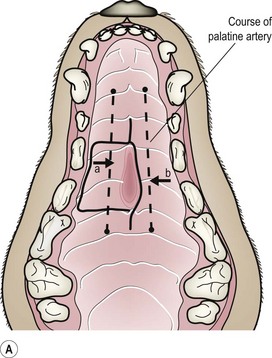

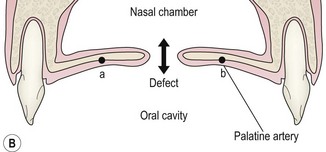

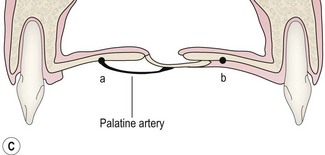

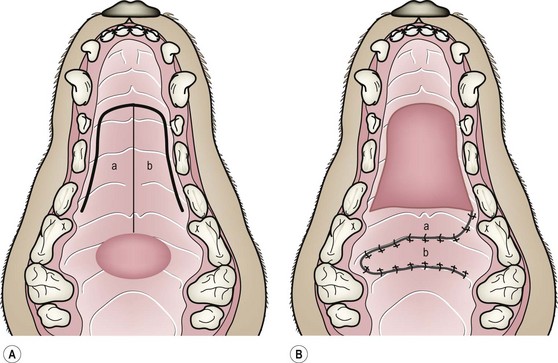

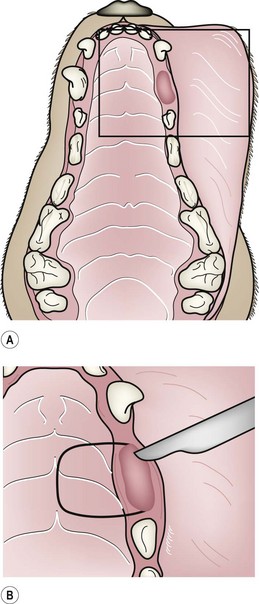

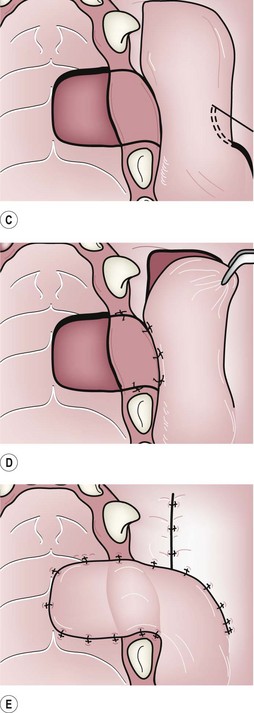

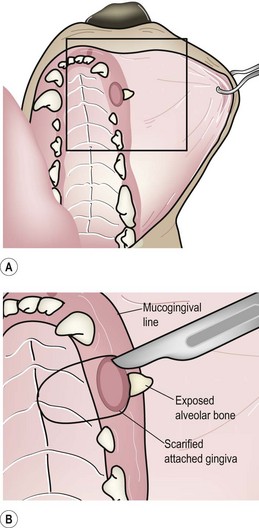

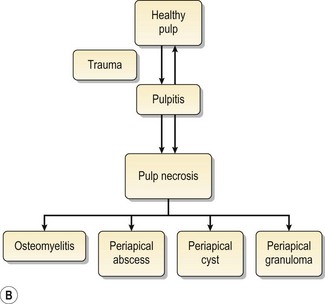

Chapter 12 The conditions which may be considered emergencies generally result from trauma to the face and oral cavity (Fig. 12.1). While they are not life-threatening, most cause discomfort and some cause severe pain and even systemic complications to the affected animal, so treatment should not be delayed. All practicing veterinarians will come across these conditions and need to be able to diagnose and provide first-line management and then refer to a specialist for treatment if indicated. The choice of closure technique will depend on: The anatomy of the lip is particularly suited to grafting techniques. Advancement, rotation and transposition flaps (Fig. 12.2) all have their uses. Fig. 12.2 Some useful grafting techniques Acquired hard palate defects in dogs and cats may occur following: Several methods of managing hard palate clefts (congenital and acquired) have been described. The choice of technique will depend on: • Location of the defect, i.e. rostral or caudal • Size and shape of the defect • Amount of tissue available for pedicle grafting procedures. Small rostral defects not involving the nasal cavity but communicating into the incisal bone will not cause nasal regurgitation and do not need to be repaired. Table 12.1 shows recommendations for choice of technique for repair of different types of hard palate defects. 1. The flaps must be tension free. Large flaps should be raised to avoid tension and ensure overlap between the flap and adjacent healthy tissue. 2. The blood supply to the flap must be retained. When raising palatal flaps it is important to identify and preserve the palatine artery. This artery exits from the palatine bone 0.5–1.0 cm medial to the upper carnassial tooth (Fig. 12.3). Palatal flaps should be full thickness mucoperiosteum with the incisions located away from the palatine artery. For vestibular flaps, find a tissue plane that will leave most of the connective tissue attached to the mucosal flap. Fig. 12.3 The palatine artery 3. Ensure that the epithelial margin of the defect is debrided. 4. Ensure that connective tissue surfaces or cut edges are sutured together, as intact epithelium will not heal to any other surface. 5. Suture lines should not lie over a defect if possible. The use of asymmetrical flaps may help avoid this. 6. Gastrostomy or pharyngostomy tubes are not necessary. Nasogastric tubes are preferable if the animal will not eat. Careful, gentle technique and planning the procedure so that there is no tension on the sutured edges is much more important in preventing dehiscence. Repair options described for hard palate lesions are: Various pedicle flaps.: These techniques are unilateral pedicle grafts based on the major palatine artery. The flap is either rotated (Fig. 12.2B) or transposed (Fig. 12.2C) to cover the defect. It is essential to debride the epithelial margins of the defect with a scalpel blade and to ensure that the flap is sutured without tension. These techniques work well for narrow defects. The Langenbeck technique.: This technique is essentially a bilateral pedicle flap and is useful for large midline defects. The main disadvantage of the Langenbeck technique is that there is a tendency for breakdown and persistence of the cleft rostrally. It is outlined in Figure 12.4. Fig. 12.4 The Langenbeck technique 1. Debride the epithelial margins of the defect with a scalpel blade. 2. Incisions are made into the mucoperiosteum at the dental margin on either side of the defect. Be careful not to transect the palatine arteries. 3. The mucoperiosteum is released from the palate with a periosteal elevator, thus raising two longitudinal strips of mucoperiosteum from the hard palate on either side of the defect. 4. The two strips of released mucoperiosteum are slid together and sutured at the midline, thus closing the cleft. 5. The exposed bone at the dental margin bilaterally is left to granulate and epithelialize. The Veau–Wardill technique.: This technique is also a bilateral pedicle flap and is useful for the repair of large midline defects. It is similar to the Langenbeck technique, except that rostral incisions extending from the dental margin to the midline bilaterally are also made (Fig. 12.5). This allows caudal as well as lateral movement of the flaps and this may help to reduce tension on closure. Fig. 12.5 The Veau–Wardill technique The double overlapping flap technique.: This technique is also called the upside down overlapping flap technique. It is useful for repair of large midline palatal defects. There is less risk of rostral breakdown using this technique. It is summarized in Figure 12.6. Fig. 12.6 The double overlapping flap technique 1. Debride the epithelial margins of the defect with a scalpel blade. 2. Incisions are made in the mucoperiosteum at the defect on one side, and along the dental margin on the other side. 3. Flaps a and b (Figure 12.6) are raised using a periosteal elevator. Make sure that the palatine arteries are not transected. 4. Flap a is folded back on itself and sutured under flap b so that the connective tissue surfaces are in contact. The sutures are preplaced in a mattress pattern. The epithelium of flap a will thus form the nasal epithelium and flap b will contribute the oral epithelium. 5. The exposed palatine bone is again left to granulate and epithelialize. The split palatal U-flap technique.: This technique is particularly useful for large caudal defects. The procedure is outlined in Figure 12.7. Fig. 12.7 The split palatal U-flap technique 1. Debride the epithelial margins of the defect with a scalpel blade. 2. Create a large U-shaped mucoperiosteal flap rostral to the defect using a periosteal elevator. 3. Incise along the midline of the raised flap to create two equally sized flaps. 4. Rotate flap a (Figure 12.7) 90° and transpose to cover the defect. 5. The medial aspect of flap a is sutured to the caudal aspect of the palatal defect and the tip of this flap is sutured to the lateral aspect of the palatal defect. 6. Flap b is rotated 90° and transposed anterior to flap a. 7. The medial aspect and tip of flap b are sutured to the edge of flap a. 8. The rostral aspect of the palate from which the flap was harvested is left to granulate. Soft palate clefts are usually congenital rather than traumatic or acquired. Closure of soft palate defects should be a double layer repair (Fig. 12.8). Incisions are made along the medial margins of the palate on each side. Blunt-ended scissors are used to separate the palate tissue on each side into dorsal and ventral flaps. The two dorsal flaps are sutured in a simple interrupted pattern to form a complete nasal epithelium, and the two ventral flaps are sutured to form a complete oral epithelium. The palate is closed to just caudal to the tonsils. Single layer repair.: The single layer repair is the surgery of choice. It works very well in most instances. The important step is to mobilize enough tissue to allow an absolutely tension-free repair. This usually requires extending the flap elevation beyond the buccal vestibule, i.e. the site at which the mucosa leaves the bone and reflects onto the interior of the cheek to become the buccal mucosa. Scarifying the edges of the defect to remove the epithelium is also essential for healing. The procedure is outlined in Figure 12.9. 1. The epithelial attachment is cut on the labial side from the caudal aspect of the 1st premolar, along the buccal edge of the defect extending to the mesial aspect of the upper lateral incisor using a scalpel blade. 2. Vertical releasing incisions are made at the mesial aspect of the lateral incisor and the distal aspect of the 1st premolar. 3. A full thickness flap is raised using a periosteal elevator. 4. It is essential that the flap extends beyond the mucogingival line, i.e. the alveolar mucosa is released from the underlying alveolar bone. 5. Dissection of the alveolar mucosa continues until sufficient tissue has been mobilized to cover the defect. This may require extending the flap elevation to or beyond the height of the buccal vestibule. 6. Split the periosteum at the base of the flap to afford complete mobility of the flap. 7. The margins of the oronasal fistula are scarified. 8. The flap is advanced across the defect and sutured to the palatine mucosa using an absorbable suture material. Double layer repair.: If single layer repair fails or if the defect is large and of long standing, a double layer technique may be used (Fig. 12.10). This technique can be modified for gingival recession or alveolar bone loss (Fig. 12.11). Fig. 12.10 Double layer oronasal fistula repair Fig. 12.11 Repair of oronasal fistula complicated by gingival recession beyond the mucogingival junction Teeth that have been affected by trauma often require endodontic treatment (see Appendix) if they are to be maintained. Tooth fracture may affect the crown (Fig. 12.12), the crown and root (Fig. 12.13) or just the root (Fig. 12.14). Fig. 12.12 Types of tooth crown injuries Fig. 12.13 Types of crown and root fractures Fig. 12.14 Horizontal root fractures Complicated crown fractures always need treatment. An exposed pulp will become inflamed and may eventually undergo necrosis. The inflammation can spread from the pulp to involve the periapical area (Fig. 12.15). A primary tooth with complicated crown fracture should be extracted to avoid damage to the adjacent developing permanent tooth. A permanent tooth, if unaffected by periodontal disease, can be treated by means of endodontic therapy. If the tooth has periodontitis or the fracture is too extensive, then extraction is the treatment of choice. In fact, with complicated crown fractures extraction is preferable to no treatment at all. Fig. 12.15 Pulp and periapical disease

Emergencies

Introduction

Soft-tissue trauma

Lip injuries

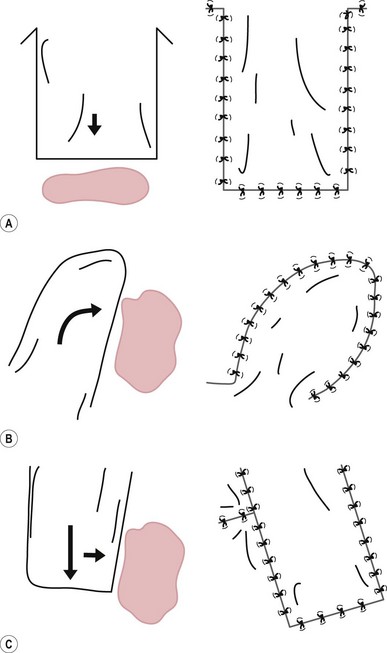

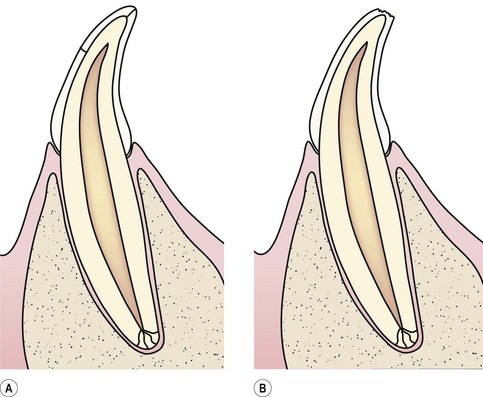

(A) Advancement flap. (B) Rotation flap. (C) Transposition flap.

Oronasal fistulae

Hard palate

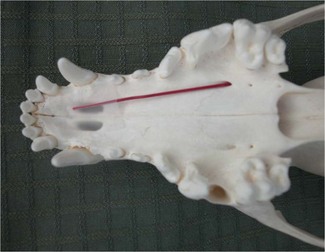

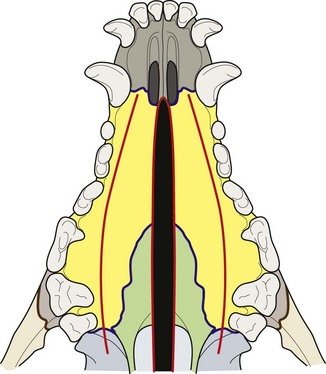

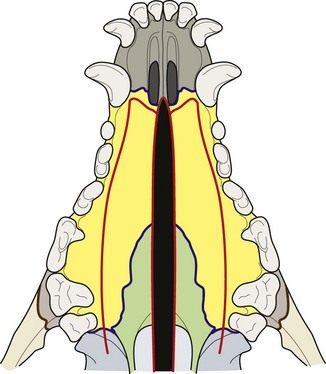

This artery exits from the palatine bone 0.5–1.0 cm medial to the upper carnassial tooth. When raising palatal flaps, it is essential to preserve the palatine artery as it is the main blood supply to the flap.

This bilateral pedicle flap is useful to repair large midline defects.

This technique is similar to the Langenbeck, except that rostral incisions extending from the dental margin to the midline bilaterally are also made. This allows caudal as well as lateral movement of the flaps and may reduce tension on closure. It is useful for the repair of large midline defects.

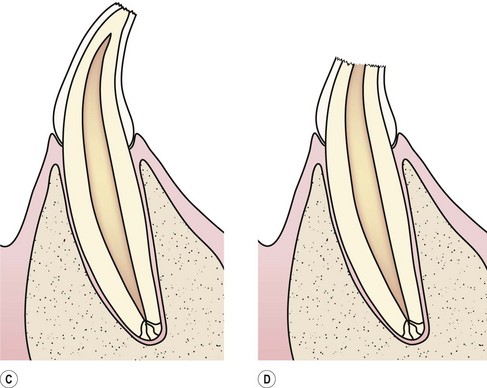

(A–C) This technique is also called the upside down overlapping flap technique. It is useful for the repair of large midline defects.

(A,B) This technique is particularly useful for large caudal defects.

Soft palate

Maxillary alveolus

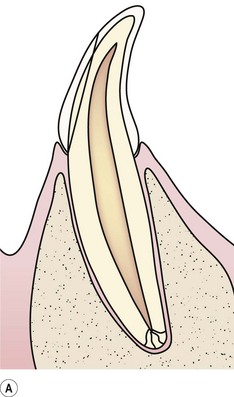

(A) Oronasal fistula at the upper left canine site. The box indicates the area drawn in detail. (B) Raising the palatal flap and scarifying the lateral margin of the fistula. (C) Laying the tension-free palatal flap and raising the mucosal finger flap. (D) The palatal flap is sutured in place. (E) The mucosal finger flap is rotated and sutured to the palatal mucosa.

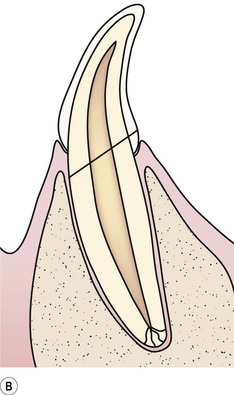

(A) Oronasal fistula at the upper left canine site. The box indicates the area drawn in detail. (B) Raising the palatal flap and scarifying the attached gingiva. (C) Laying the palatal flap and raising the mucosal finger flap. (D) The lifted palatal flap is sutured in place and the finger flap lifted. (E) The mucosal finger flap is rotated and sutured to the palatal mucosa.

Traumatic tooth injuries

Tooth fracture

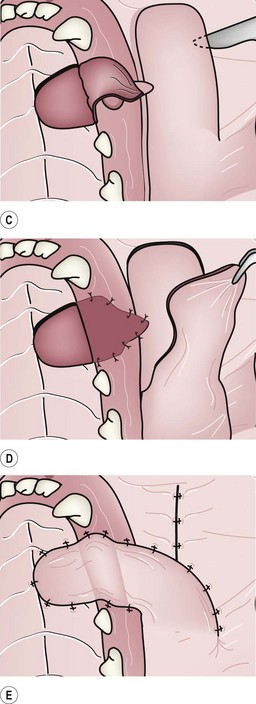

(A) Fracture lines in the enamel without loss of tooth substance. The fractures extend only to the dentino-enamel junction. They require no treatment, but the tooth should be monitored for signs of pulp and periapical disease. (B) Uncomplicated crown fracture affecting only the enamel. Treatment consists of smoothing off jagged edges. (C) Uncomplicated crown fracture exposing dentine. Restoration is indicated, especially if the fracture line is close to the pulp. (D) Complicated crown fracture, i.e. the pulp chamber is exposed. This is an indication for endodontic therapy.

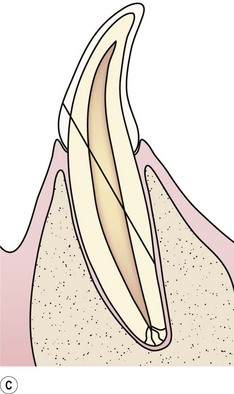

(A) Uncomplicated crown and root fracture. (B) Complicated crown and root fracture. (C) Complicated crown and root fracture, which usually involves damage to the alveolar bone. (D) Long axis crown and root fracture. This is an absolute indication for extraction.

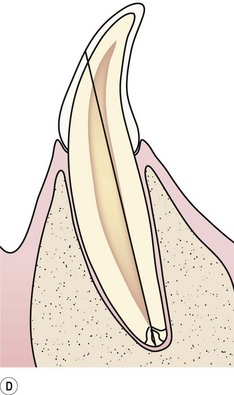

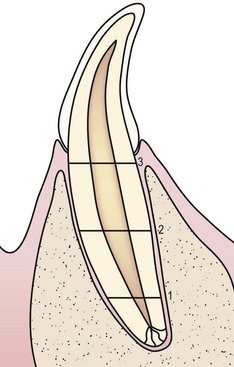

(1) Fracture of apical segment. (2) Midroot fracture. Both 1 and 2 will heal with immobilization. (3) Fracture of the coronal root close to the gingival margin. This fracture is unlikely to heal. If the root is to be retained, it needs endodontic treatment.

Crown

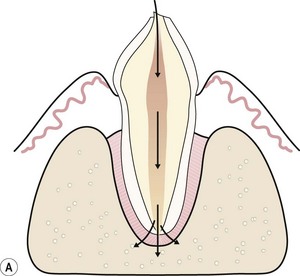

An exposed pulp will become inflamed and eventually undergo necrosis. The inflammation can spread from the pulp to involve the periapical area (A). The types of pathology that may occur in the periapical area (B) range from localized reactions (granuloma, cyst, abscess) around the apex to osteomyelitis.![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Emergencies