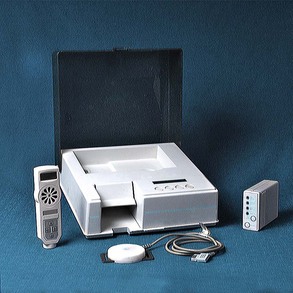

Chapter 208 Recently a system for monitoring labor and fetal viability in the bitch or queen has become available commercially (Veterinary Perinatal Services, Inc.). This system is intended for use by veterinarians in the clinical setting when evaluating a bitch or queen in labor or by dog or cat fanciers or kennel or cattery managers with veterinary supervision in the home or kennel/cattery setting. The Veterinary Perinatal Service (VPS) design is based on labor monitoring systems used routinely in human obstetrics. The uterine monitoring system consists of a tocodynamometer (sensor), a recorder, and a modem (Figure 208-1). The uterine sensor detects changes in intrauterine and intraamniotic pressures. The sensor is strapped over a lightly clipped area of the dam’s caudolateral abdomen using an elasticized strap. The sensor’s recorder is worn in a small backpack placed over the caudal shoulder area in medium and large bitches or adjacent to this area in smaller bitches or queens (Figure 208-2). Dams should be at rest in the nesting box, cage, or a crate during the monitoring sessions. The monitoring equipment is well tolerated. Subsequent to each recording session, data are transferred from the recorder to the service center using a modem with the telephone. Figure 208-1 Veterinary obstetrical monitoring equipment consists of a tocodynamometer (sensor, recorder, and modem, right) and hand-held Doppler unit (left). Figure 208-2 A monitoring session showing a pregnant Airedale bitch with tocodynamometer sensor in place. The sensor is placed over a lightly clipped area of the gravid lateral abdomen. Fetal heart rate monitoring, performed with either a real-time ultrasound scanhead (5 to 7.5 MHz) or a handheld Doppler unit, is best used with dams in lateral recumbency, using acoustic coupling gel (Figure 208-3). Visualization of the fetal cardiac valve motion enables estimation of the heart rate with real-time ultrasound. Directing the handheld Doppler perpendicularly over a fetus results in a characteristic amplification of the fetal heart sounds, distinct from maternal arterial, digestive, or cardiac sounds, enabling audible determination of fetal heart rates. The presence of fetal distress is reflected by sustained deceleration of the heart rates. Decelerations associated with uterine contractions suggest mismatch between the size of the fetus and the birth canal or fetal malposition or malposture. Malpresentation is generally not a problem in canine or feline deliveries because approximately 50% are delivered in caudal longitudinal presentation. Transient accelerations occur with normal fetal movement. Figure 208-3 Evaluating fetal heart rate with a handheld Doppler. Fetal heart rates can be detected audibly or read from the unit.

Dystocia Management

Detecting Abnormalities in Canine and Feline Labor

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree