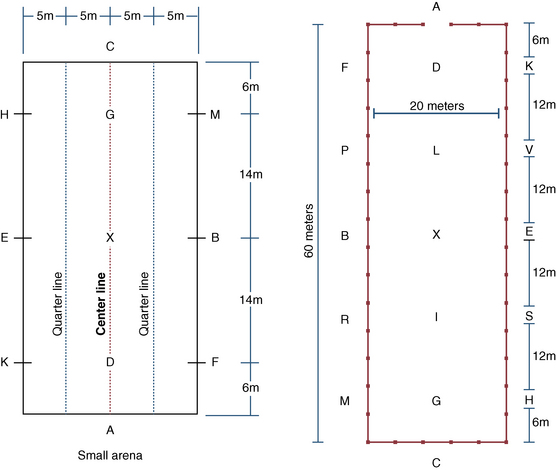

CHAPTER 24 Dressage is a term derived from the French term dresser, which means to train. Originating centuries ago in Europe, dressage became much more prevalent during the Renaissance period. It was later that progressive, strategic training regimens were developed by the great riding masters. This is referred to as classical dressage. In the twenty-first century, modern dressage is a competitive equestrian sport, with common training protocols that demonstrate changes from, but clear relationship to, those used in classical dressage (Chamberlain, 2006). Reference to the website of The Fédération Équestre Internationale (FEI), the governing body of international dressage competitions (http://www.fei.org/disciplines/dressage/about-dressage), indicates that dressage is considered one of the highest forms of horse training. The site goes on to state that at completion of training, the horse and rider are expected to perform, from memory, a series of predetermined movements. Dressage competitions are held worldwide, with the Olympic and World Equestrian Games being considered the pinnacles of the sport. The key purpose of the training discipline is to have the horse undertake a relatively standardized training protocol whereby the limits of a horse’s natural athletic ability are approached. This should be associated with the horse’s willingness to perform, with the outcome being achievement of its maximal potential as a riding horse. The objective is for the horse to respond without hesitation to the rider’s commands (aids), with these aids being kept to a minimum and the horse appearing relaxed and free of apparent effort. Commentators at televised events such as the Olympic Games often refer to dressage as equine ballet. Although the discipline has ancient roots in Europe, with the Greeks laying claim to early dressage “type” training around 400 bc. Dressage was first recognized as an important equestrian pursuit during the Renaissance. The great European riding masters of that period developed a sequential training system that has changed little since then. Classical dressage is still considered the basis of modern dressage (Chamberlain, 2006). Competitions in modern dressage involve undertaking a riding test, a process in which horse and rider are expected to undertake series of prescribed movements. The movements are graded in difficulty according to the training level of the horse and become progressively more difficult as the horse advances to higher levels of performance. A dressage test is conducted in a standardized arena, with judges assessing each of the movements. Judges use an objective standard for each movement and ascribe a score on a scale of 0 to 10: 0 if the movement is not executed and 10 being the perfect score, which is almost never awarded. As such 9 is considered an excellent very high score. As a general rule, horses and riders achieving consistent average scores of 6 or above are generally qualified to move up to the next level of competition (http://www.usef.org/_IFrames/breedsDisciplines/discipline/alldressage/about.aspx). The two accepted sizes of arena (dressage manège) are referred to as small and standard. The small arena is 20 m × 40 m (66 × 131 ft) and tends to be used for lower level competition. The standard arena is 20 m × 60m (66 × 197 ft) used for all upper-level national and international competitions (Figure 24-1). FIGURE 24-1 Small and standard dressage arenas with the accepted measurements (meters) and letter configurations. Each size of arena has letters (often associated with cones) assigned to positions around the edges of the arena to specify where the requisite movements are to be performed. For the small arena, the letters are A-K-E-H-C-M-B-F with A located nearest the point of entry to the arena and counted off in a clockwise fashion. Additionally, a set of letters are placed down the center line of the arena: D-X-G, with X being at the center. The standard arena, used in dressage and eventing competitions, has the letters A-K-V-E-S-H-C-M-R-B-P-F around the periphery. The letters D-L-X-I-G are in the middle (short ends) of the arena, again with X being on the midline (see Figure 24-1). As such, dressage has a defined centerline (from A to C, going through X in the middle) as well as two quarter-lines (halfway between the centerline and the long sides of each arena) (see Figure 24-1). Among the several theories explaining the origins of the markings of the arenas, the two probable explanations exist for the lettering surrounding the manège. Markings found on the walls of the Royal Manstall (Mews or Stables) of the Imperial German Court in Berlin (prior to 1918) suggest that they indicated where each courtier’s or rider’s horse was to stand awaiting its rider. The Manstall stabled 300 of the Kaiser’s horses, as well as carriages and sledges. The “hof” (stable yard) was large enough for horses and their riders to parade for “morning exercise” or assemble for ceremonial parades. The length of the hof was three times greater than the width: 20 m × 60 m, hence the likely origin of the accepted size of the standard arena today. The markings on the walls of the Manstall are provided in Box 24-1. The letters D-L-X-I-G were added in 1932 for the Berlin Olympic Games. The origin or meaning of these extra letters is not well explained. At the start of the test, the horse enters at A. A judge is always sitting at C, although for upper-level competition, up to five judges are present at different places around the arena—at C, E, B, M, and H—which allows the horse to be seen in each movement from all angles. This helps prevent certain faults from going unnoticed, as it may be difficult for a judge to see everything from only one area of the arena. For example, the horse’s straightness going across the diagonal may be assessed by the judges at M and H.

Dressage tests, movements, and training: A primer

Dressage arenas

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Dressage tests, movements, and training: A primer

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree